In what types of cases can one not build an opening (window or door) from his house? In extending an existing door, there are issues regarding not only seeing into the neighbor’s property but also in doing so, one gains rights to more space of the commonly shared courtyard as the space directly in front of the door belongs to the owner of the house. What if one has something that juts out into public space? There are two stories brought of people who came before rabbis who ruled they had to get rid of it but the rabbis themselves had something similar or the same in their own property. The stories highlight the needs of leaders to hold themselves to higher standards or at least to the same standards as they demand of others. In the context of things one must do to remember the destruction, the gemara discusses the concept of moderation and the concept of not demanding something of the people that they will not be able to keep.

Bava Batra 60

Share this shiur:

Bava Batra

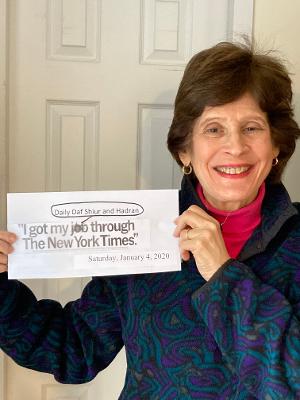

Masechet Bava Batra is sponsored by Lori Stark in loving memory of her mother in law, Sara Shapiro z”l and her father Nehemiah Sosewitz z”l.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Bava Batra

Masechet Bava Batra is sponsored by Lori Stark in loving memory of her mother in law, Sara Shapiro z”l and her father Nehemiah Sosewitz z”l.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Bava Batra 60

וְלִסְתּוֹם – לְאַלְתַּר הָוֵי חֲזָקָה, שֶׁאֵין אָדָם עָשׂוּי שֶׁסּוֹתְמִים אוֹרוֹ בְּפָנָיו וְשׁוֹתֵק.

And to seal, i.e., if one sealed another’s window in his presence, there is an acquired privilege established immediately to keep the window sealed, as it is not common behavior for a person to have his source of light sealed in his presence and remain silent. The fact that he did not immediately protest indicates that the one who sealed the window had the legal right to do so unilaterally, or that the owner of the window agreed.

לָקַח בַּיִת בְּחָצֵר אַחֶרֶת – לֹא יִפְתָּחֶנּוּ לַחֲצַר הַשּׁוּתָּפִין. מַאי טַעְמָא? מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּרְבֶּה עֲלֵיהֶם אֶת הַדֶּרֶךְ.

§ The mishna teaches that if one purchased a house in another, adjacent courtyard, he may not open the house into a courtyard belonging to partners. The Gemara explains: What is the reason for this? Because by adding residents to the courtyard it increases their traffic, and the residents of the courtyard do not wish to be disturbed by additional people passing through.

אֵימָא סֵיפָא: אֶלָּא אִם רָצָה – בּוֹנֶה אֶת הַחֶדֶר לִפְנִים מִבֵּיתוֹ, וּבוֹנֶה עֲלִיָּיה עַל גַּבֵּי בֵּיתוֹ. וַהֲלֹא מַרְבֶּה עָלָיו אֶת הַדֶּרֶךְ! אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: מַאי חֶדֶר? שֶׁחֲלָקוֹ בִּשְׁנַיִם, וּמַאי עֲלִיָּיה? אַפְּתָאי.

The Gemara questions this. But say the last clause of the mishna: Rather, if he desired to build a loft, he may build a room within his house, or he may build a loft above his house, and have it open into his house, not directly into the courtyard. But if he does so, isn’t there still a concern that it increases the traffic? Rav Huna said as an explanation: What does the mishna mean when it says that he may build a room? It means that he may divide an existing room in two. And what is the loft to which the mishna is referring? It is an internal story created by dividing an existing space into two stories.

מַתְנִי׳ לֹא יִפְתַּח אָדָם לַחֲצַר הַשּׁוּתָּפִין פֶּתַח כְּנֶגֶד פֶּתַח וְחַלּוֹן כְּנֶגֶד חַלּוֹן. הָיָה קָטָן – לֹא יַעֲשֶׂנּוּ גָּדוֹל, אֶחָד – לֹא יַעֲשֶׂנּוּ שְׁנַיִם. אֲבָל פּוֹתֵחַ הוּא לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים פֶּתַח כְּנֶגֶד פֶּתַח וְחַלּוֹן כְּנֶגֶד חַלּוֹן. הָיָה קָטָן – עוֹשֶׂה אוֹתוֹ גָּדוֹל, וְאֶחָד – עוֹשֶׂה אוֹתוֹ שְׁנַיִם.

MISHNA: A person may not open an entrance opposite another entrance or a window opposite another window toward a courtyard belonging to partners, so as to ensure that the residents will enjoy a measure of privacy. If there was a small entrance he may not enlarge it. If there was one entrance he may not fashion it into two. But one may open an entrance opposite another entrance or a window opposite another window toward the public domain. Similarly, if there was a small entrance he may enlarge it, and if there was one entrance he may fashion it into two.

גְּמָ׳ מְנָהָנֵי מִילֵּי? אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״וַיִּשָּׂא בִלְעָם אֶת עֵינָיו, וַיַּרְא אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל שֹׁכֵן לִשְׁבָטָיו״ – מָה רָאָה? רָאָה שֶׁאֵין פִּתְחֵי אׇהֳלֵיהֶם מְכֻוּוֹנִין זֶה לְזֶה, אָמַר: רְאוּיִן הַלָּלוּ שֶׁתִּשְׁרֶה עֲלֵיהֶם שְׁכִינָה.

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: From where are these matters, i.e., that one may not open an entrance opposite another entrance, or a window opposite another window, derived? Rabbi Yoḥanan says that the verse states: “And Balaam lifted up his eyes, and he saw Israel dwelling tribe by tribe; and the spirit of God came upon him” (Numbers 24:2). The Gemara explains: What was it that Balaam saw that so inspired him? He saw that the entrances of their tents were not aligned with each other, ensuring that each family enjoyed a measure of privacy. And he said: If this is the case, these people are worthy of having the Divine Presence rest on them.

הָיָה קָטָן – לֹא יַעֲשֶׂנּוּ גָּדוֹל. סָבַר רָמֵי בַּר חָמָא לְמֵימַר, בַּר אַרְבְּעֵי לָא לִישַׁוְּיֵיהּ בַּר תְּמָנְיָא – דְּקָא שָׁקֵיל תְּמָנְיָא בְּחָצֵר; אֲבָל בַּר תַּרְתֵּי לִישַׁוְּיֵיהּ בַּר אַרְבְּעֵי – שַׁפִּיר דָּמֵי; אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא, מָצֵי אָמַר לֵיהּ: בְּפִיתְחָא זוּטְרָא מָצֵינָא לְאִצְטְנוֹעֵי מִינָּךְ, בְּפִיתְחָא רַבָּה לָא מָצֵינָא אִצְטְנוֹעֵי מִינָּךְ.

The mishna teaches that if there was a small entrance he may not enlarge it. Rami bar Ḥama thought to say this means that if the entrance was the width of four cubits, one may not fashion it to the width of eight cubits, as he would then be allowed to take eight corresponding cubits in the courtyard. The halakha is that one is entitled to utilize the area of the courtyard up to a depth of four cubits along the width of the opening. But if the entrance was the width of two cubits and one wishes to fashion it to the width of four cubits, one may well do so, as in any event he already had the right to use an area of four cubits by four cubits in front of the entrance. Rava said to him: This is not so, as his neighbor can say to him: I can conceal myself from you with there being a small entrance, but I cannot conceal myself from you with there being a large entrance.

אֶחָד – לֹא יַעֲשֶׂנּוּ שְׁנַיִם. סָבַר רָמֵי בַּר חָמָא לְמֵימַר, בַּר אַרְבְּעֵי – לָא לִישַׁוְּיֵיהּ תְּרֵי בְּנֵי תַּרְתֵּי תַּרְתֵּי, דְּקָא שָׁקֵיל תַּמְנֵי בְּחָצֵר; אֲבָל בַּר תַּמְנֵי, לִישַׁוְּיֵיהּ בְּנֵי אַרְבְּעֵי אַרְבְּעֵי – שַׁפִּיר דָּמֵי; אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא, מָצֵי אֲמַר לֵיהּ: בְּחַד פִּיתְחָא מָצֵינָא אִצְטְנוֹעֵי מִינָּךְ, בִּתְרֵי לָא מָצֵינָא אִצְטְנוֹעֵי מִינָּךְ.

The mishna teaches that if there was one entrance he may not fashion it into two. In this case as well, Rami bar Ḥama thought to say that this means if the entrance was the width of four cubits he may not make it into two openings, each the width of two cubits, as he would then be allowed to take eight corresponding cubits in the courtyard, four for each entrance. But if it was the width of eight cubits and he wishes to make it into two openings, each the width of four cubits, he may well do so, as in any event he already had the right to use an area of eight cubits by four cubits in front of his entrance. Rava said to him: This is not so, as his neighbor can say to him: I can conceal myself from you with there being one entrance, but I cannot conceal myself from you with there being two entrances.

אֲבָל פּוֹתֵחַ הוּא לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים פֶּתַח כְּנֶגֶד פֶּתַח. דְּאָמַר לֵיהּ: סוֹף סוֹף, הָא בָּעֵית אִצְטְנוֹעֵי מִבְּנֵי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים.

The mishna teaches: But one may open an entrance opposite another entrance or a window opposite another window toward the public domain. Why is this so? Because he can say to the one who wishes to protest: Ultimately, you must conceal yourself from the people of the public domain. Since you cannot stop them from passing by and therefore cannot engage in behavior that requires privacy with your entrance open, it is of no consequence to you if I open an entrance as well.

מַתְנִי׳ אֵין עוֹשִׂין חָלָל תַּחַת רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים – בּוֹרוֹת, שִׁיחִין וּמְעָרוֹת. רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר מַתִּיר כְּדֵי שֶׁתְּהֵא עֲגָלָה מְהַלֶּכֶת וּטְעוּנָה אֲבָנִים. אֵין מוֹצִיאִין זִיזִין וּגְזוּזְטְרָאוֹת לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, אֶלָּא אִם רָצָה – כּוֹנֵס לְתוֹךְ שֶׁלּוֹ, וּמוֹצִיא. לָקַח חָצֵר וּבָהּ זִיזִין וּגְזוּזְטְרָאוֹת – הֲרֵי זוֹ בְּחֶזְקָתָהּ.

MISHNA: One may not form an empty space beneath the public domain by digging pits, ditches, or caves. Rabbi Eliezer deems it permitted for one to do so, provided that he places a covering strong enough that a wagon laden with stones would be able to tread on it without breaking it, therefore ensuring that the empty space will not cause any damage to those in the public domain. One may not extend projections or balconies [ugzuztraot] into the public domain. Rather, if he desired to build one he may draw back into his property by moving his wall, and extend the projection to the end of his property line. If one purchased a courtyard in which there are projections and balconies extending into the public domain, this courtyard retains its presumptive status, i.e., the owner has the acquired privilege of their use, and the court does not demand their removal.

גְּמָ׳ וְרַבָּנַן – זִימְנִין דְּמִפְּחִית וְלָאו אַדַּעְתֵּיהּ.

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: Rabbi Eliezer’s opinion that if the covering of the space is strong enough to support a wagon laden with stones then it is permitted to dig out the empty space, is eminently reasonable; but what do the Rabbis hold? The Gemara answers: There are times when the cover erodes over time, and he is not aware, thereby potentially causing damage to those in the public domain.

אֵין מוֹצִיאִין זִיזִין וּגְזוּזְטְרָאוֹת וְכוּ׳. רַבִּי אַמֵּי הֲוָה לֵיהּ זִיזָא דַּהֲוָה נָפֵיק לִמְבוֹאָה; וְהַהוּא גַּבְרָא נָמֵי הֲוָה לֵיהּ זִיזָא, דַּהֲוָה מַפֵּיק לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים. הֲווֹ קָא מְעַכְּבִי עֲלֵיהּ בְּנֵי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים. אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי אַמֵּי, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: זִיל קוֹץ.

The mishna teaches that one may not extend projections or balconies into the public domain. The Gemara relates: Rabbi Ami had a projection that protruded into an alleyway, and a certain man also had a projection that protruded into the public domain, and the general public was preventing the man from leaving it there, as it interfered with traffic. He came before Rabbi Ami, who said to him: Go sever your projection.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: וְהָא מָר נָמֵי אִית לֵיהּ! דִּידִי לִמְבוֹאָה מַפֵּיק – בְּנֵי מְבוֹאָה מָחֲלִין גַּבַּאי; דִּידָךְ לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים מַפֵּיק, מַאן מָחֵיל גַּבָּךְ?

The man said to him: But the Master also has a similar projection. Rabbi Ami said to him: It is different, as mine protrudes into an alleyway, where a limited number of people live, and the residents of the alleyway waive their right to protest to me. Yours protrudes into the public domain, which does not belong to any specific individuals. Who can waive their right to protest to you?

רַבִּי יַנַּאי הֲוָה לֵיהּ אִילָן הַנּוֹטֶה לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים. הֲוָה הָהוּא גַּבְרָא דַּהֲוָה לֵיהּ נָמֵי אִילָן הַנּוֹטֶה לִרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, אֲתוֹ בְּנֵי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים הֲווֹ קָא מְעַכְּבִי עִילָּוֵיהּ. אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי יַנַּאי, אֲמַר לֵיהּ:

The Gemara relates: Rabbi Yannai had a tree that was leaning into the public domain. There was a certain man who also had a tree that was leaning into the public domain, and the general public was preventing him from leaving it there, insisting he cut it down, as required by the mishna (27b). He came before Rabbi Yannai, who said to him:

זִיל הָאִידָּנָא וְתָא לִמְחַר. בְּלֵילְיָא, שַׁדַּר קַצְיֵיהּ לְהָהוּא דִּידֵיהּ.

Go now, and come tomorrow. At night, Rabbi Yannai sent and had someone cut down that tree that belonged to him.

לִמְחַר אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: זִיל קוֹץ. אָמַר לֵיהּ: הָא מָר נָמֵי אִית לֵיהּ! אָמַר לֵיהּ: זִיל חֲזִי; אִי קוּץ דִּידִי – קוֹץ דִּידָךְ, אִי לָא קוּץ דִּידִי – לָא תִּקּוֹץ אַתְּ.

The next day, that man came before Rabbi Yannai, who said to him: Go, cut down your tree. The man said to him: But the Master also has a tree that leans into the public domain. Rabbi Yannai said to him: Go and see: If mine is cut down, then cut yours down. If mine is not cut down, you do not have to cut yours down, either.

מֵעִיקָּרָא מַאי סְבַר וּלְבַסּוֹף מַאי סְבַר? מֵעִיקָּרָא סְבַר: נִיחָא לְהוּ לִבְנֵי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, דְּיָתְבִי בְּטוּלֵּיהּ. כֵּיוָן דַּחֲזָא דְּקָא מְעַכְּבִי, שַׁדַּר קַצְיֵיהּ. וְלֵימָא לֵיהּ: זִיל קוֹץ דִּידָךְ, וַהֲדַר אֶקּוֹץ דִּידִי! מִשּׁוּם דְּרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ, דְּאָמַר: ״הִתְקוֹשְׁשׁוּ וָקוֹשּׁוּ״ – קְשׁוֹט עַצְמְךָ וְאַחַר כָּךְ קְשׁוֹט אֲחֵרִים.

The Gemara asks: At the outset what did Rabbi Yannai hold, and ultimately, what did he hold? The Gemara replies: At the outset, he held that the general public is amenable to having the tree there, as they sit in its shade. Once he saw that they were preventing someone else who owned a tree from keeping his, he understood that it was only out of respect that they did not object to his tree being there. He therefore sent someone to cut it down. The Gemara asks: But why did he tell the man to return the next day? Let him say to him: Go cut down your tree, and then I will cut mine down. The Gemara answers: Because of the statement of Reish Lakish, who said: The verse states: “Gather yourselves together and gather [hitkosheshu vakoshu]” (Zephaniah 2:1), and this can be explained homiletically to mean: Adorn [keshot] yourself and afterward adorn others, i.e., act properly before requiring others to do so.

אֲבָל אִם רָצָה – כּוֹנֵס לְתוֹךְ שֶׁלּוֹ וּמוֹצִיא. אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: כָּנַס וְלֹא הוֹצִיא, מַהוּ שֶׁיַּחֲזוֹר וְיוֹצִיא? רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: כָּנַס – מוֹצִיא. וְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אָמַר: כָּנַס – אֵינוֹ מוֹצִיא.

§ The mishna teaches that one may not extend projections or balconies into the public domain. Rather, if he desired to build one he may draw back into his property by moving his wall, and extend the projection to the end of his property line. A dilemma was raised before the Sages: If one drew back into his property but did not extend the projection at that time, what is the halakha concerning whether he may return and extend it at a later date? Rabbi Yoḥanan says: If one drew back into his property, he may extend it even later, and Reish Lakish says: If one drew back into his property but did not build the projection at that time, he may not extend it later.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב לְרַבִּי יִרְמְיָה בַּר תַּחְלִיפָא, אַסְבְּרַהּ לָךְ: לְהוֹצִיא – כּוּלֵּי עָלְמָא לָא פְּלִיגִי דְּמוֹצִיא, כִּי פְּלִיגִי – לְהַחֲזִיר כְּתָלִים לִמְקוֹמָן; וְאִיפְּכָא אִיתְּמַר – רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: אֵינוֹ מַחְזִיר, וְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אָמַר: מַחְזִיר.

The Gemara presents an alternative version of the dispute: Rabbi Ya’akov said to Rabbi Yirmeya bar Taḥlifa: I will explain the matter to you. To later extend a projection, everyone agrees that he may extend it, since he is adding within his own property. Where they disagree is with regard to whether he may return the walls to their prior place. And with regard to this disagreement the opposite was stated: Rabbi Yoḥanan says he may not return the walls to their prior place, and Reish Lakish says he may return them.

רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: אֵינוֹ מַחְזִיר – מִשּׁוּם דְּרַב יְהוּדָה, דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: מֶצֶר שֶׁהֶחֱזִיקוּ בּוֹ רַבִּים, אָסוּר לְקַלְקְלוֹ. וְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אָמַר: מַחְזִיר – הָנֵי מִילֵּי הֵיכָא דְּלֵיכָּא רַוְוחָא, הָכָא הָא אִיכָּא רַוְוחָא.

Rabbi Ya’akov explains their reasoning: Rabbi Yoḥanan says that he may not return the walls to their prior place because of the statement of Rav Yehuda, as Rav Yehuda says: With regard to a path that the public has established as a public thoroughfare, it is prohibited to ruin it, i.e., to prevent people from using it. Once the public has become accustomed to using the place where his wall had stood, he may not repossess that space. And Reish Lakish says that he may return the walls to their prior place, because that matter applies in a case where there is no space, i.e., if he were to move back the wall there would be no space for the public to walk, but here there is space, since they can still walk through the public domain.

לָקַח חָצֵר וּבָהּ זִיזִין וּגְזוּזְטְרָאוֹת – הֲרֵי הִיא בְּחֶזְקָתָהּ. אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: נָפְלָה, חוֹזֵר וּבוֹנֶה אוֹתָהּ.

The mishna teaches that if one purchased a courtyard in which there are projections and balconies extending into the public domain, this courtyard retains its presumptive status, allowing the owner to use the projections. Rav Huna says: If the wall of the courtyard fell, he may return and build it as it was, including the projections or balconies.

מֵיתִיבִי: אֵין מְסַיְּידִין וְאֵין מְכַיְּירִין וְאֵין מְפַיְּיחִין בַּזְּמַן הַזֶּה. לָקַח חָצֵר מְסוּיֶּדֶת, מְכוּיֶּרֶת, מְפוּיַּחַת – הֲרֵי זוֹ בְּחֶזְקָתָהּ. נָפְלָה – אֵינוֹ חוֹזֵר וּבוֹנֶה אוֹתָהּ!

The Gemara raises an objection based on that which is taught in a baraita (Tosefta 9:17): One may not plaster, and one may not tile, and one may not paint [mefayyeḥin] images in the present, as a sign of mourning for the destruction of the Temple. But if one purchased a courtyard that was plastered, tiled, or painted with images, this courtyard retains its presumptive status, and it is assumed that it was done in a permitted manner. If it then fell, he may not return and build it in its previous form. This indicates that one may not rebuild a building in a manner that is prohibited, even if there was an acquired privilege to maintain it in that manner.

אִיסּוּרָא שָׁאנֵי.

The Gemara answers: A case of forbidden matters is different, i.e., in the case of the baraita, he may not rebuild it because it is prohibited for him to do so. In this mishna, the issue is encroachment upon the rights of others, and once he had an acquired privilege to use the projections or balconies, he maintains that right.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: לֹא יָסוּד אָדָם אֶת בֵּיתוֹ בְּסִיד. וְאִם עֵירַב בּוֹ חוֹל אוֹ תֶּבֶן – מוּתָּר. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: עֵירַב בּוֹ חוֹל – הֲרֵי זֶה טְרַכְסִיד, וְאָסוּר; תֶּבֶן – מוּתָּר.

§ With regard to the ruling of the above-quoted baraita, the Sages taught (Tosefta, Sota 15:9): A person may not plaster his house with plaster, but if he mixed sand or straw into the plaster, which dulls its luster, it is permitted. Rabbi Yehuda says: If he mixed sand into it, it is white cement [terakesid], which is of a higher quality than standard plaster, and it is prohibited, but if he mixed in straw, it is permitted.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: כְּשֶׁחָרַב הַבַּיִת בַּשְּׁנִיָּה, רַבּוּ פְּרוּשִׁין בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁלֹּא לֶאֱכוֹל בָּשָׂר וְשֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁתּוֹת יַיִן. נִטְפַּל לָהֶן רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ, אָמַר לָהֶן: בָּנַי, מִפְּנֵי מָה אִי אַתֶּם אוֹכְלִין בָּשָׂר וְאֵין אַתֶּם שׁוֹתִין יַיִן? אָמְרוּ לוֹ: נֹאכַל בָּשָׂר – שֶׁמִּמֶּנּוּ מַקְרִיבִין עַל גַּבֵּי מִזְבֵּחַ, וְעַכְשָׁיו בָּטֵל? נִשְׁתֶּה יַיִן – שֶׁמְּנַסְּכִין עַל גַּבֵּי הַמִּזְבֵּחַ, וְעַכְשָׁיו בָּטֵל?

§ Having mentioned the prohibition against plastering, which is a sign of mourning over the destruction of the Temple, the Gemara discusses related matters. The Sages taught in a baraita (Tosefta, Sota 15:11): When the Temple was destroyed a second time, there was an increase in the number of ascetics among the Jews, whose practice was to not eat meat and to not drink wine. Rabbi Yehoshua joined them to discuss their practice. He said to them: My children, for what reason do you not eat meat and do you not drink wine? They said to him: Shall we eat meat, from which offerings are sacrificed upon the altar, and now the altar has ceased to exist? Shall we drink wine, which is poured as a libation upon the altar, and now the altar has ceased to exist?

אָמַר לָהֶם: אִם כֵּן, לֶחֶם לֹא נֹאכַל – שֶׁכְּבָר בָּטְלוּ מְנָחוֹת! אֶפְשָׁר בְּפֵירוֹת. פֵּירוֹת לֹא נֹאכַל – שֶׁכְּבָר בָּטְלוּ בִּכּוּרִים! אֶפְשָׁר בְּפֵירוֹת אֲחֵרִים. מַיִם לֹא נִשְׁתֶּה – שֶׁכְּבָר בָּטֵל נִיסּוּךְ הַמַּיִם! שָׁתְקוּ.

Rabbi Yehoshua said to them: If so, we will not eat bread either, since the meal-offerings that were offered upon the altar have ceased. They replied: You are correct. It is possible to subsist with produce. He said to them: We will not eat produce either, since the bringing of the first fruits have ceased. They replied: You are correct. We will no longer eat the produce of the seven species from which the first fruits were brought, as it is possible to subsist with other produce. He said to them: If so, we will not drink water, since the water libation has ceased. They were silent, as they realized that they could not survive without water.

אָמַר לָהֶן: בָּנַי, בּוֹאוּ וְאוֹמַר לָכֶם: שֶׁלֹּא לְהִתְאַבֵּל כׇּל עִיקָּר אִי אֶפְשָׁר – שֶׁכְּבָר נִגְזְרָה גְּזֵרָה; וּלְהִתְאַבֵּל יוֹתֵר מִדַּאי אִי אֶפְשָׁר – שֶׁאֵין גּוֹזְרִין גְּזֵירָה עַל הַצִּבּוּר, אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן רוֹב צִבּוּר יְכוֹלִין לַעֲמוֹד בָּהּ – דִּכְתִיב: ״בַּמְּאֵרָה אַתֶּם נֵאָרִים, וְאֹתִי אַתֶּם קֹבְעִים; הַגּוֹי כֻּלּוֹ״ –

Rabbi Yehoshua said to them: My children, come, and I will tell you how we should act. To not mourn at all is impossible, as the decree was already issued and the Temple has been destroyed. But to mourn excessively as you are doing is also impossible, as the Sages do not issue a decree upon the public unless a majority of the public is able to abide by it, as it is written: “You are cursed with the curse, yet you rob Me, even this whole nation” (Malachi 3:9), indicating that the prophet rebukes the people for neglecting observances only if they were accepted by the whole nation.

אֶלָּא כָּךְ אָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים: סָד אָדָם אֶת בֵּיתוֹ בְּסִיד, וּמְשַׁיֵּיר בּוֹ דָּבָר מוּעָט; וְכַמָּה? אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: אַמָּה עַל אַמָּה. אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: כְּנֶגֶד הַפֶּתַח.

Rabbi Yehoshua continues: Rather, this is what the Sages said: A person may plaster his house with plaster, but he must leave over a small amount in it without plaster to remember the destruction of the Temple. The Gemara interjects: And how much is a small amount? Rav Yosef said: One cubit by one cubit. Rav Ḥisda said: This should be opposite the entrance, so that it is visible to all.

עוֹשֶׂה אָדָם כׇּל צׇרְכֵי סְעוּדָה, וּמְשַׁיֵּיר דָּבָר מוּעָט; מַאי הִיא? אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: כָּסָא דְהַרְסָנָא.

Rabbi Yehoshua continues: The Sages said that a person may prepare all that he needs for a meal, but he must leave out a small item to remember the destruction of the Temple. The Gemara interjects: What is this small item? Rav Pappa said: Something akin to small, fried fish.

עוֹשָׂה אִשָּׁה כׇּל תַּכְשִׁיטֶיהָ, וּמְשַׁיֶּירֶת דָּבָר מוּעָט; מַאי הִיא? אָמַר רַב: בַּת צִדְעָא. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אִם אֶשְׁכָּחֵךְ יְרוּשָׁלִָם, תִּשְׁכַּח יְמִינִי. תִּדְבַּק לְשׁוֹנִי לְחִכִּי וְגוֹ׳״.

Rabbi Yehoshua continues: The Sages said that a woman may engage in all of her cosmetic treatments, but she must leave out a small matter to remember the destruction of the Temple. The Gemara interjects: What is this small matter? Rav said: She does not remove hair from the place on the temple from which women would remove hair. The source for these practices is a verse, as it is stated: “If I forget you, Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its cunning. Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I remember you not; if I set not Jerusalem above my highest joy” (Psalms 137:5–6).

מַאי ״עַל רֹאשׁ שִׂמְחָתִי״? אָמַר רַב יִצְחָק: זֶה אֵפֶר מִקְלֶה שֶׁבְּרֹאשׁ חֲתָנִים. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב פָּפָּא לְאַבָּיֵי: הֵיכָא מַנַּח לֵהּ? בִּמְקוֹם תְּפִילִּין, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״לָשׂוּם לַאֲבֵלֵי צִיּוֹן, לָתֵת לָהֶם פְּאֵר תַּחַת אֵפֶר״.

The Gemara asks: What is the meaning of: Above my highest [rosh] joy? Rav Yitzḥak says: This is referring to the burnt ashes that are customarily placed on the head [rosh] of bridegrooms at the time of their wedding celebrations, to remember the destruction of the Temple. Rav Pappa said to Abaye: Where are they placed? Abaye replied: On the place where phylacteries are placed, as it is stated: “To appoint to them that mourn in Zion, to give to them a garland in place of ashes” (Isaiah 61:3). Since phylacteries are referred to as a garland (see Ezekiel 24:17), it may be inferred from this verse that the ashes were placed in the same place as the phylacteries.

וְכׇל הַמִּתְאַבֵּל עַל יְרוּשָׁלַיִם – זוֹכֶה וְרוֹאֶה בְּשִׂמְחָתָהּ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״שִׂמְחוּ אֶת יְרוּשָׁלַםִ וְגוֹ׳״.

The baraita continues: And anyone who mourns for the destruction of Jerusalem will merit and see its joy, as it is stated: “Rejoice with Jerusalem, and be glad with her, all that love her; rejoice for joy with her, all that mourn for her” (Isaiah 66:10).

תַּנְיָא, אָמַר רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל בֶּן אֱלִישָׁע: מִיּוֹם שֶׁחָרַב בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, דִּין הוּא שֶׁנִּגְזוֹר עַל עַצְמֵנוּ שֶׁלֹּא לֶאֱכוֹל בָּשָׂר וְלֹא לִשְׁתּוֹת יַיִן; אֶלָּא אֵין גּוֹזְרִין גְּזֵרָה עַל הַצִּבּוּר אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן רוֹב צִבּוּר יְכוֹלִין לַעֲמוֹד בָּהּ.

It is taught in a baraita (Tosefta, Sota 15:10) that Rabbi Yishmael ben Elisha said: From the day that the Temple was destroyed, by right, we should decree upon ourselves not to eat meat and not to drink wine, but the Sages do not issue a decree upon the public unless a majority of the public is able to abide by it.

וּמִיּוֹם שֶׁפָּשְׁטָה מַלְכוּת הָרְשָׁעָה, שֶׁגּוֹזֶרֶת עָלֵינוּ גְּזֵירוֹת רָעוֹת וְקָשׁוֹת, וּמְבַטֶּלֶת מִמֶּנּוּ תּוֹרָה וּמִצְוֹת, וְאֵין מַנַּחַת אוֹתָנוּ לִיכָּנֵס לִשְׁבוּעַ הַבֵּן, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ: לִישׁוּעַ הַבֵּן; דִּין הוּא שֶׁנִּגְזוֹר עַל עַצְמֵנוּ שֶׁלֹּא לִישָּׂא אִשָּׁה וּלְהוֹלִיד בָּנִים, וְנִמְצָא זַרְעוֹ שֶׁל אַבְרָהָם אָבִינוּ כָּלֶה מֵאֵלָיו;

And from the day that the wicked kingdom, i.e., Rome, spread, who decree evil and harsh decrees upon us, and nullify Torah study and the performance of mitzvot for us, and do not allow us to enter the celebration of the first week of a son, i.e., circumcision, and some say: To enter the celebration of the salvation of a firstborn son; by right we should each decree upon ourselves not to marry a woman and not to produce offspring, and it will turn out that the descendants of Abraham our forefather will cease to exist on their own, rather than being forced into a situation where there are sons who are not circumcised.

אֶלָּא הַנַּח לָהֶם לְיִשְׂרָאֵל – מוּטָב שֶׁיִּהְיוּ שׁוֹגְגִין, וְאַל יִהְיוּ מְזִידִין.

But concerning a situation such as this, the following principle is applied: Leave the Jews alone and do not impose decrees by which they cannot abide. It is better that they be unwitting sinners, who do not know that what they are doing is improper considering the circumstances, and not be intentional wrongdoers, who marry and procreate despite knowing that they should not.

הַדְרָן עֲלָךְ חֶזְקַת הַבָּתִּים