What is a homeowner’s liability if someone brings in items without permission or with permission? What is the liability of damages caused by the item by the one who brought it in? By permitting to bring in the item, the homeowner assumes responsibility for any damages to the item. Rebbi disagrees and says unless the owner explicitly said he/she would watch it, the owner has not accepted the responsibility of a shomer. Suppose fruits are left without permission and the animal gets damaged from eating them. Rav holds the owner of the fruits is not responsible (only if the animal tripped on the fruits) because he/she can say, “What was the animal doing eating my fruits?” Three difficulties are raised against Rav but are resolved.

Bava Kamma 47

Share this shiur:

Bava Kamma

Masechet Bava Kamma is sponsored by the Futornick Family in loving memory of their fathers and grandfathers, Phillip Kaufman and David Futornick.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Bava Kamma

Masechet Bava Kamma is sponsored by the Futornick Family in loving memory of their fathers and grandfathers, Phillip Kaufman and David Futornick.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

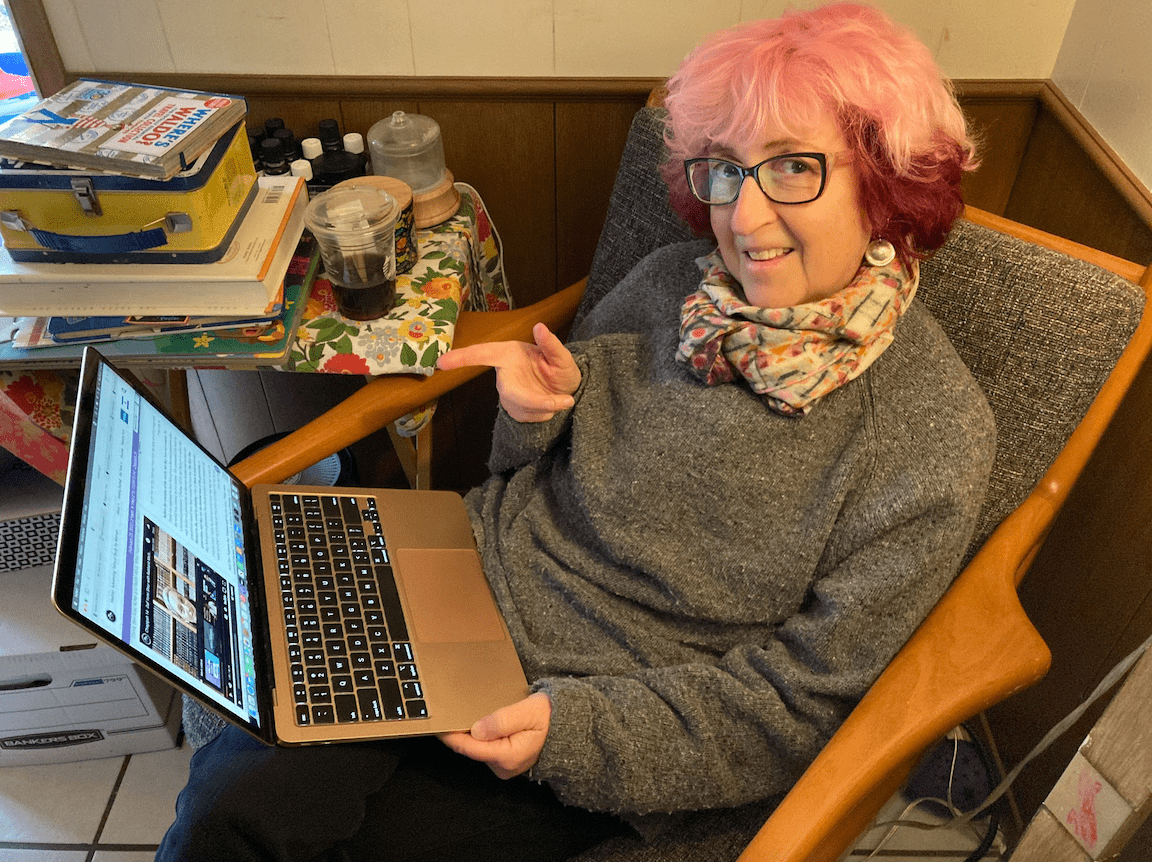

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Bava Kamma 47

לֵיתַהּ לְפָרָה – מִשְׁתַּלֵּם רְבִיעַ נֶזֶק מִוָּלָד.

if the cow is not here, e.g., it went astray, only one-quarter of the cost of the damage is reimbursed from the offspring.

טַעְמָא דְּלָא יָדְעִינַן אִי הֲוָה וָלָד בַּהֲדַהּ כִּי נְגַחָה, אִי לָא הֲוָה; אֲבָל אִי פְּשִׁיטָא לַן דַּהֲוָה וָלָד בַּהֲדַהּ כִּי נְגַחָה – מִשְׁתַּלֵּם כּוּלֵּיהּ חֲצִי נֶזֶק מִוָּלָד;

The Gemara infers: According to Rava, the reason for paying only one-quarter of the cost of the damage is that we do not know if the offspring was with it, as a fetus, when the cow gored or whether it was not. But if it is obvious to us that the offspring was with it as a fetus when it gored, the full amount of half the cost of the damage may be reimbursed from the offspring if the cow is not there.

רָבָא לְטַעְמֵיהּ, דְּאָמַר רָבָא: פָּרָה שֶׁהִזִּיקָה – גּוֹבֶה מִוְּלָדָהּ. מַאי טַעְמָא? גּוּפַהּ הִיא. תַּרְנְגוֹלֶת שֶׁהִזִּיקָה – אֵינוֹ גּוֹבֶה מִבֵּיצָתָהּ. מַאי טַעְמָא? פִּירְשָׁא בְּעָלְמָא הוּא.

The Gemara comments: In this respect, Rava conforms to his line of reasoning, as Rava says: In the case of a cow that caused damage while pregnant, the injured party collects compensation from its offspring, i.e., the offspring that had been a fetus at the time of the goring. What is the reason? It is because it is considered an integral part of its body and therefore may be used to collect payment. By contrast, in the case of a hen that caused damage, the injured party does not collect compensation from its egg. Payment can be collected only from the body of the hen. What is the reason? The egg is simply a secretion and not an integral part of the hen’s body.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: אֵין שָׁמִין לַפָּרָה בִּפְנֵי עַצְמָהּ וְלַוָּלָד בִּפְנֵי עַצְמוֹ, אֶלָּא שָׁמִין לַוָּלָד עַל גַּב פָּרָה. שֶׁאִם אִי אַתָּה אוֹמֵר כֵּן – נִמְצָא אַתָּה מַכְחִישׁ אֶת הַמַּזִּיק.

§ And Rava also says: When assessing the damage inflicted by a goring ox on a cow whose newborn calf is found dead by its side, the court does not appraise the damage to the cow by itself and the damage to the offspring by itself. Rather, the court appraises the offspring together with the cow and evaluates the overall damage inflicted on the pregnant cow, which will be slightly less than it would be with two separate evaluations. The reason for this is that if you do not say this, you will be found to have ultimately weakened the one liable for damage by inflicting a loss on him, as the market value of a newborn calf is greater than the difference in market value between a pregnant cow and one that is not pregnant.

וְכֵן אַתָּה מוֹצֵא בְּקוֹטֵעַ יַד עַבְדּוֹ שֶׁל חֲבֵירוֹ. וְכֵן אַתָּה מוֹצֵא בְּמַזִּיק שָׂדֶה שֶׁל חֲבֵירוֹ.

And similarly, you find this principle in a case where someone severed the hand of another’s slave. The difference in value between a slave with a hand and a slave without a hand is assessed, rather than determining how much money the owner would request in exchange for allowing the hand of his slave to be cut off. And similarly, you also find this principle in a case of one who causes damage to part of another’s field. The court appraises not the garden bed that was eaten or trampled, but the depreciation in value of the bed as part of the surrounding area. This results in a smaller payment, as the damage appears less significant in the context of a larger area.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב אַחָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרָבָא לְרַב אָשֵׁי: וְאִי דִּינָא הוּא, לִיכְחוֹשׁ מַזִּיק!

Rav Aḥa, son of Rava, said to Rav Ashi: The main reason invoked by Rava is that otherwise you will be found to have ultimately weakened the one liable for damage. But if this is the halakha of assessing the damage, then let the one liable for damage be weakened by losing money.

מִשּׁוּם דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ: פָּרָה מְעַבַּרְתָּא אַזֵּיקְתָּךְ, פָּרָה מְעַבַּרְתָּא שָׁיֵימְנָא לָךְ.

Rav Ashi answered: This is because the one liable for damage can say to him: I caused damage to you through injuring a pregnant cow, and so I am assessing the value of a pregnant cow for you. Therefore, it is not correct to evaluate separately the damage to the cow and the damage to the offspring.

פְּשִׁיטָא, פָּרָה דְּחַד וּוָלָד דְּחַד – פִּיטְמָא לְבַעַל פָּרָה. נִפְחָא מַאי? רַב פָּפָּא אָמַר: לְבַעַל פָּרָה, רַב אַחָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב אִיקָא אָמַר: חוֹלְקִין. וְהִלְכְתָא: חוֹלְקִין.

The Gemara raises a question: It is obvious that in a case where the cow belonged to one person and the offspring belonged to another that the compensation for the cow’s loss of fat is paid to the owner of the cow. The additional value that the cow had due to the fact that it was fatter due to the pregnancy is paid to the owner of the cow. The question is: What is the halakha concerning the cow’s bulk? There is an increase in value of a pregnant cow that is attributed to its improved appearance, which results from its carrying a fetus. Who is considered the injured party with regard to that sum? Rav Pappa said: This too belongs to the owner of the cow, whereas Rav Aḥa, son of Rav Ika, said: They divide the restitution. And the halakha is that they divide the restitution.

מַתְנִי׳ הַקַּדָּר שֶׁהִכְנִיס קְדֵרוֹתָיו לַחֲצַר בַּעַל הַבַּיִת שֶׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת, וְשִׁבְּרָתַן בְּהֶמְתּוֹ שֶׁל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת – פָּטוּר. וְאִם הוּזְּקָה בָּהֶן – בַּעַל הַקְּדֵרוֹת חַיָּיב. וְאִם הִכְנִיס בִּרְשׁוּת – בַּעַל הֶחָצֵר חַיָּיב.

MISHNA: In the case of a potter who brought his pots into a homeowner’s courtyard without permission, and the homeowner’s animal broke the pots, the homeowner is exempt. If the owner’s animal was injured by the pots, the owner of the pots is liable. But if the potter brought them inside with permission, the owner of the courtyard is liable if his animal caused damage to the pots.

הִכְנִיס פֵּירוֹתָיו לַחֲצַר בַּעַל הַבַּיִת שֶׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת, וַאֲכָלָתַן בְּהֶמְתּוֹ שֶׁל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת – פָּטוּר. וְאִם הוּזְּקָה בָּהֶן – בַּעַל הַפֵּירוֹת חַיָּיב. וְאִם הִכְנִיס בִּרְשׁוּת – בַּעַל הֶחָצֵר חַיָּיב.

Similarly, if someone brought his produce into the homeowner’s courtyard without permission, and the homeowner’s animal ate them, the homeowner is exempt. If his animal was injured by them, e.g., if it slipped on them, the owner of the produce is liable. But if he brought his produce inside with permission, the owner of the courtyard is liable for the damage caused by his animal to them.

הִכְנִיס שׁוֹרוֹ לַחֲצַר בַּעַל הַבַּיִת שֶׁלֹּא

Similarly, if one brought his ox into the homeowner’s courtyard without

בִּרְשׁוּת, וּנְגָחוֹ שׁוֹרוֹ שֶׁל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת, אוֹ שֶׁנְּשָׁכוֹ כַּלְבּוֹ שֶׁל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת – פָּטוּר. נָגַח הוּא שׁוֹרוֹ שֶׁל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת – חַיָּיב. נָפַל לְבוֹרוֹ, וְהִבְאִישׁ מֵימָיו – חַיָּיב. הָיָה אָבִיו אוֹ בְּנוֹ לְתוֹכוֹ – מְשַׁלֵּם אֶת הַכּוֹפֶר. וְאִם הִכְנִיס בִּרְשׁוּת – בַּעַל הֶחָצֵר חַיָּיב.

permission, and the homeowner’s ox gored it or the homeowner’s dog bit it, the homeowner is exempt. If it gored the homeowner’s ox, the owner of the goring ox is liable. Furthermore, if the ox that he brought into the courtyard without permission fell into the owner’s pit and contaminated its water, the owner of the ox is liable to pay compensation for despoiling the water. If the homeowner’s father or son were inside the pit at the time the ox fell and the person died as a result, the owner of the ox pays the ransom. But if he brought the ox into the courtyard with permission, the owner of the courtyard is liable for the damage caused.

רַבִּי אוֹמֵר: בְּכוּלָּן אֵינוֹ חַיָּיב, עַד שֶׁיְּקַבֵּל עָלָיו לִשְׁמוֹר.

Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi says: The homeowner is not liable in any of the cases in the mishna, even if he gave his permission for the items to be brought into his premises, unless he explicitly accepts responsibility upon himself to safeguard them.

גְּמָ׳ טַעְמָא דְּשֶׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת, הָא בִּרְשׁוּת – לָא מִיחַיַּיב בַּעַל קְדֵירוֹת בְּנִזְקֵי בְהֶמְתּוֹ דְּבַעַל חָצֵר, וְלָא אָמְרִינַן קַבּוֹלֵי קַבֵּיל בַּעַל קְדֵירוֹת נְטִירוּתָא דִּבְהֶמְתּוֹ דְּבַעַל חָצֵר;

GEMARA: From the first case of the mishna, it can be inferred that the reason the potter is liable is that he brought his pots into another’s courtyard without permission. But if he brought them in with permission, the potter would not be liable for damage caused to the courtyard owner’s animal; and we do not say that the potter accepted responsibility for the safeguarding of the courtyard owner’s animal from his own pots.

מַנִּי – רַבִּי הִיא, דְּאָמַר: כֹּל בִּסְתָמָא – לָא קַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ נְטִירוּתָא.

Whose opinion is this? It is that of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who says at the conclusion of the mishna that any case where permission is granted to allow an item into one’s premises without specification, i.e., without an explicit agreement as to who is responsible for safeguarding the item, it is assumed that with regard to each party, he has not accepted upon himself the responsibility of safeguarding the item. Therefore, the potter who received permission to bring his pots into the owner’s courtyard similarly did not accept responsibility to safeguard against damage to the property of the owner of the courtyard.

אֵימָא סֵיפָא: אִם הִכְנִיס בִּרְשׁוּת – בַּעַל חָצֵר חַיָּיב. אֲתָאן לְרַבָּנַן, דְּאָמְרִי: בִּסְתָמָא נָמֵי קַבּוֹלֵי קַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ נְטִירוּתָא.

But say the latter clause: If the potter brought them into the courtyard with permission, the owner of the courtyard is liable. In this case, we arrive at the opinion of the Rabbis, who disagree with Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi and say that, even in a case where permission is granted to allow an item into one’s premises without specification, where the owner merely said he could bring them into the courtyard, the homeowner accepts upon himself responsibility for safeguarding the items to ensure that they are not damaged, as well.

וְתוּ, רַבִּי אוֹמֵר: בְּכוּלָּן אֵינוֹ חַיָּיב, עַד שֶׁיְּקַבֵּל עָלָיו בַּעַל הַבַּיִת לִשְׁמוֹר. רֵישָׁא וְסֵיפָא רַבִּי, וּמְצִיעֲתָא רַבָּנַן?!

And furthermore, the end of the mishna states: Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi says that the owner of the courtyard is not liable in any of the cases in the mishna, even if he gave his permission for the items to be brought into his premises, unless the homeowner explicitly accepts responsibility upon himself to safeguard them. Therefore, it emerges that the first clause and the last clause of the mishna are in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, but the middle clause of the mishna is in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis. Is this a reasonable way to read the mishna?

אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא: תִּבְרַהּ; מִי שֶׁשָּׁנָה זוֹ – לֹא שָׁנָה זוֹ. רָבָא אָמַר: כּוּלַּהּ רַבָּנַן הִיא, וּבִרְשׁוּת – שְׁמִירַת קְדֵירוֹת קִבֵּל עָלָיו בַּעַל הֶחָצֵר, וַאֲפִילּוּ נִשְׁבְּרוּ בָּרוּחַ.

The Gemara answers that Rabbi Zeira said: This mishna is disjointed and doesn’t follow a single opinion. Rather, the one who taught this clause of the mishna did not teach that clause of the mishna. Rava said: The beginning of the mishna is entirely in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis. In the case where the potter received permission to place his pots there, the owner of the courtyard accepted responsibility upon himself for the safeguarding of the pots, and even to the extent that if the pots broke due to the wind, he would be liable. The owner of the pots, by contrast, did not accept any responsibility to ensure that his items would not cause damage.

הִכְנִיס פֵּירוֹתָיו לַחֲצַר בַּעַל הַבַּיִת וְכוּ׳. אָמַר רַב: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא שֶׁהוּחְלְקָה בָּהֶן, אֲבָל אָכְלָה – פָּטוּר. מַאי טַעְמָא? הֲוָה לַהּ שֶׁלֹּא תֹּאכַל.

§ The mishna teaches: If he brought his produce into the homeowner’s courtyard without permission, and the owner’s animal was injured by the produce, he is liable. Rav says: They taught this halakha only in a case where the animal slipped on it and fell, but if it ate from the produce and was injured, he is exempt. What is the reason? The animal should not have eaten it, and it was not the owner of the fruit who acted improperly but the animal itself.

אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: אָמֵינָא, כִּי נָיֵים וְשָׁכֵיב רַב אֲמַר לְהָא שְׁמַעְתָּא. דְּתַנְיָא: הַנּוֹתֵן סַם הַמָּוֶת לִפְנֵי בֶּהֱמַת חֲבֵירוֹ – פָּטוּר מִדִּינֵי אָדָם, וְחַיָּיב בְּדִינֵי שָׁמַיִם. סַם הַמָּוֶת הוּא דְּלָא עֲבִידָא דְּאָכְלָה; אֲבָל פֵּירוֹת, דַּעֲבִידָא דְּאָכְלָה – בְּדִינֵי אָדָם נָמֵי מִיחַיַּיב! וְאַמַּאי? הֲוָיא לַהּ שֶׁלֹּא תֹּאכַל!

Rav Sheshet said: I say that Rav stated this halakha while dozing and lying down, and it is not entirely precise, as it is taught in a baraita: One who places poison before another’s animal is exempt according to human laws but liable according to the laws of Heaven. From the above statement, it may be inferred that it is specifically where he put poison before the animal that he is exempt, since it is not suitable for eating. But if he put produce before it, which is suitable for eating, and the animal dies from eating it, he is also liable according to human laws. The Gemara analyzes this ruling: But why is he liable? Here also Rav’s logic can be invoked, that the animal should not have eaten it. Therefore, this baraita poses a difficulty for Rav.

אָמְרִי: הוּא הַדִּין אֲפִילּוּ פֵּירוֹת – נָמֵי פָּטוּר מִדִּינֵי אָדָם; וְהָא קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן – דַּאֲפִילּוּ סַם הַמָּוֶת נָמֵי, דְּלָא עֲבִידָא דְּאָכְלָה – חַיָּיב בְּדִינֵי שָׁמַיִם.

In order to explain Rav’s statement, the Sages said: The same is true, that even if the animal was injured by eating the produce, he would also be exempt according to human laws, and this baraita teaches us this, that even in the case of poison, which is not suitable for eating, the one who placed the poison before the animal is liable according to the laws of Heaven.

וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא: סַם הַמָּוֶת נָמֵי – בְּאַפְרַזְתָּא, דְּהַיְינוּ פֵּירֵי.

And if you wish, say instead that the case where the baraita exempts from liability according to human laws the one who placed poison before the animal is referring to an item suitable for eating as well, such as afrazta, a type of herb that appears edible for animals but is actually poisonous. Therefore, this herb is halakhically equivalent to any other produce for which he is exempt from liability according to human laws, since, as Rav explained, the animal should not have eaten it.

מֵיתִיבִי: הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁנִּכְנְסָה לִטְחוֹן חִטִּים אֵצֶל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת שֶׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת, וַאֲכָלָתַן בְּהֶמְתּוֹ שֶׁל בַּעַל הַבַּיִת – פָּטוּר. אִם הוּזְּקָה – חַיֶּיבֶת. וְאַמַּאי? נֵימָא: הֲוָה לַהּ שֶׁלֹּא תֹּאכַל!

The Gemara raises an objection to Rav’s statement from a baraita: In the case of a woman who entered the house of a homeowner without permission in order to grind wheat, and the homeowner’s animal ate the wheat, he is exempt. Moreover, if the homeowner’s animal was injured by the wheat, the woman is liable. Now according to Rav’s explanation, why is she liable? Let us say here as well that the animal should not have eaten it.

אָמְרִי: וּמִי עֲדִיפָא מִמַּתְנִיתִין – דְּאוֹקֵימְנָא שֶׁהוּחְלְקָה בָּהֶן?

In order to explain Rav’s statement, the Sages said: What is the difficulty here? Is this baraita preferable to the mishna that we interpreted as a scenario where the animal slipped on the produce? Similarly, the baraita is also referring to a case where the animal was injured by slipping on the wheat, not by eating it.

וּדְקָאָרֵי לַהּ מַאי קָאָרֵי לַהּ? אָמַר לָךְ: בִּשְׁלָמָא מַתְנִיתִין, קָתָנֵי ״אִם הוּזְּקָה בָּהֶן״ – שֶׁהוּחְלְקָה בָּהֶן הוּא; אֲבָל הָכָא, קָתָנֵי ״אִם הוּזְּקָה״ וְלָא קָתָנֵי ״בָּהֶן״ – אֲכִילָה הוּא דְּקָתָנֵי.

The Gemara asks: And he who asked it, why did he ask it? This answer seems obvious. The Gemara answers: The questioner could have said to you: Granted, the mishna that teaches: If it is injured by them [bahen], is referring to a case where the animal slipped on them [bahen]. But here in the baraita it teaches the phrase: If it is injured, and it does not teach the additional term: Bahen. Since this case is immediately preceded by the case of: And the owner’s animal ate them, it is reasonable to surmise that when the baraita teaches the case of the animal being injured, the injury is due to eating.

וְאִידַּךְ אָמַר לָךְ: לָא שְׁנָא.

The Gemara notes: And the other one, i.e., the one who provided the answer, could have said to you in response: There is no difference whether it states: It was injured, or: It was injured by them, as in both cases the injury can be explained as resulting from slipping and not from eating.

תָּא שְׁמַע: הִכְנִיס שׁוֹרוֹ לַחֲצַר בַּעַל הַבַּיִת שֶׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת, וְאָכַל חִטִּין וְהִתְרִיז וָמֵת – פָּטוּר. וְאִם הִכְנִיס בִּרְשׁוּת – בַּעַל הֶחָצֵר חַיָּיב. וְאַמַּאי? הֲוָה לֵיהּ שֶׁלֹּא יֹאכַל!

Come and hear a proof from a baraita: If one brought his ox into a homeowner’s courtyard without permission, and the ox ate wheat belonging to the homeowner and consequently was stricken with diarrhea and died, then the homeowner is exempt. But if the ox’s owner brought it into the courtyard with permission, the owner of the courtyard is liable. The Gemara comments: Why, in the latter case, is the owner liable for the damage to the ox? Shouldn’t the assertion: The ox shouldn’t have eaten it, be invoked, and any injury that follows is the responsibility of the ox’s owner?

אָמַר רָבָא: בִּרְשׁוּת אַשֶּׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת קָרָמֵית? בִּרְשׁוּת – שְׁמִירַת שׁוֹרוֹ קִבֵּל עָלָיו, וַאֲפִילּוּ חָנַק אֶת עַצְמוֹ.

Rava said in response: Are you raising a contradiction from a case with permission and applying it against a case without permission? There is no difficulty here, since in the case where the ox’s owner brought the ox into the courtyard with permission, the homeowner thereby accepted responsibility upon himself for safeguarding against any damage to the other’s ox. And even if the ox strangled itself, he would still be liable.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: הֵיכָא דְּקַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ נְטִירוּתָא, מַהוּ? דְּנַפְשֵׁיהּ הוּא דְּקַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ, אוֹ דִלְמָא אֲפִילּוּ נְטִירוּתָא דְּעָלְמָא קַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ?

§ A dilemma was raised before the Sages: In a case where the owner of the courtyard accepted upon himself responsibility for safeguarding the items entering his premises, what is the halakha? Did he accept upon himself only the responsibility of safeguarding himself and his animals from causing damage? Or, perhaps he even accepted responsibility upon himself for safeguarding against all forms of damage that originate from the outside.

תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּתָנֵי רַב יְהוּדָה בַּר סִימוֹן בִּנְזָקִין דְּבֵי קַרְנָא: הִכְנִיס פֵּירוֹתָיו לַחֲצַר בַּעַל הַבַּיִת שֶׁלֹּא בִּרְשׁוּת, וּבָא שׁוֹר מִמָּקוֹם אַחֵר וַאֲכָלָן – פָּטוּר. וְאִם הִכְנִיס בִּרְשׁוּת – חַיָּיב. מַאן פָּטוּר וּמַאן חַיָּיב? לָאו פָּטוּר – בַּעַל חָצֵר, [וְחַיָּיב – בַּעַל חָצֵר]?

Come and hear a solution based on that which Rav Yehuda bar Simon taught in the tractate of Nezikin from the school of Karna: If one brought his produce into a homeowner’s courtyard without permission, and an ox came from elsewhere and ate it, he is exempt. But if one brought the produce into the courtyard with permission, he is liable. The Gemara clarifies: Who is the phrase: He is exempt, referring to, and who is the phrase: He is liable, referring to? Does it not mean that the owner of the courtyard is exempt and the owner of the courtyard is liable? This would indicate that by granting permission for the produce to be brought in, he accepts responsibility to safeguard against other damage as well, such as that caused by another ox entering from the outside.

אָמְרִי: לָא; פָּטוּר בַּעַל הַשּׁוֹר, וְחַיָּיב בַּעַל הַשּׁוֹר.

In response, they said that this interpretation should be rejected: No, it means that the owner of the ox that causes damage is exempt, and the owner of the ox is liable.

וְאִי בַּעַל הַשּׁוֹר,

The Gemara asks: But if it is referring to the owner of the ox,