The Mishna rules that if an animal falls into someone’s property and benefits, the owner pays for the benefit but not the damage caused. What type of benefit is the Mishna discussing – eating or that the produce softened the fall, or both? How does this (softening the fall) differ from one who chases a lion away from destroying another’s property, for which one receives no compensation at all? If the animal moved to a different garden bed and ate there – is the owner still exempt from damages and only pays what the owner benefited? There are several different opinions about what stage the owner becomes liable for damages. How does one assess the payment for damages of produce growing in a field? One opinion is that it is evaluated based on that produce being in a field of a beit seah which is in a field that can hold sixty seah sixty seah. Others hold something similar but with minor adaptations. The rabbis question whether this assessment method is used also for a person who damages another’s field or only if it is damage caused by property.

Bava Kamma 58

Share this shiur:

Bava Kamma

Masechet Bava Kamma is sponsored by the Futornick Family in loving memory of their fathers and grandfathers, Phillip Kaufman and David Futornick.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Bava Kamma

Masechet Bava Kamma is sponsored by the Futornick Family in loving memory of their fathers and grandfathers, Phillip Kaufman and David Futornick.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

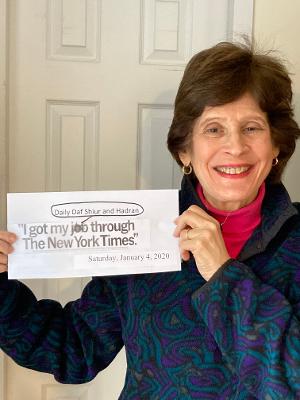

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Bava Kamma 58

״לָא מִבַּעְיָא״ קָאָמַר: לָא מִבַּעְיָא אָכְלָה – דִּמְשַׁלֶּמֶת מַה שֶּׁנֶּהֱנֵית; אֲבָל נֶחְבְּטָה – אֵימָא מַבְרִיחַ אֲרִי מִנִּכְסֵי חֲבֵירוֹ הוּא, וּמַה שֶּׁנֶּהֱנֵית נָמֵי לָא מְשַׁלֵּם; קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

one cannot make such an inference from Rav’s statement. Rav is speaking utilizing the style of: It is not necessary, and this is how to understand his statement: It is not necessary to state that if the animal fell into the garden and ate from its produce, that the owner pays for the benefit that it derives. But if the produce softened the blow of striking the ground and thereby the animal avoided injury, one might say that the owner of the animal should not pay, on the grounds that the owner of the garden may be viewed, analogously, to one who repels a lion from another’s property. In such a case, although the latter benefited from his action, he is not obligated to pay for it. Similarly in this case, one might think that the owner of the animal does not pay even for the benefit that the animal derived. For this reason Rav teaches us that the owner of the animal must pay for this benefit as well.

וְאֵימָא הָכִי נָמֵי!

The Gemara asks: But why not say that this is indeed the halakha, and the owner of the animal should be exempt for paying for the benefit of his animal not being injured?

מַבְרִיחַ אֲרִי מִנִּכְסֵי חֲבֵירוֹ – מִדַּעְתּוֹ הוּא, הַאי – לָאו מִדַּעְתּוֹ. אִי נָמֵי, מַבְרִיחַ אֲרִי מִנִּכְסֵי חֲבֵירוֹ – לֵית לֵיהּ פְּסֵידָא, הַאי – אִית לֵיהּ פְּסֵידָא.

The Gemara answers: One who repels a lion from another’s property does so with intent, knowing that he would be ineligible for payment. By contrast, this owner of the garden did not act with intent and would have preferred for the incident not to have happened. Alternatively, one could say that one who repels a lion from another’s property does not thereby have any loss himself. By contrast, this owner of the garden has a loss, in that his produce is damaged.

הֵיכִי נָפַל? רַב כָּהֲנָא אָמַר: שֶׁהוּחְלְקָה בְּמֵימֵי רַגְלֶיהָ, רָבָא אָמַר: שֶׁדְּחָפַתָּה חֲבֶרְתָּהּ.

The Gemara asks: How did the animal fall? In which case does this halakha apply? Rav Kahana says: It slipped on its own urine. Rava says: Another animal belonging to the same owner pushed it, causing it to fall there.

מַאן דְּאָמַר שֶׁדְּחָפַתָּה חֲבֶרְתָּהּ – כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן שֶׁהוּחְלְקָה בְּמֵימֵי רַגְלֶיהָ. וּמַאן דְּאָמַר שֶׁהוּחְלְקָה בְּמֵימֵי רַגְלֶיהָ – אֲבָל דְּחָפַתָּה חֲבֶרְתָּהּ, פָּשְׁעָה, וּמְשַׁלֶּמֶת מַה שֶּׁהִזִּיקָה; דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ: אִיבְּעִי לָךְ עַבּוֹרֵי חֲדָא חֲדָא.

The Gemara explains: Rava, the one who says that the mishna is referring to a case where another animal pushed it, in which case the owner pays only for the benefit that the animal derived and is exempt from paying for the damage caused, holds that all the more so this halakha would apply in a case where it slipped on its urine, which is beyond the owner’s control. But Rav Kahana, the one who says that the mishna is referring to a case where the animal slipped on its urine, holds that if, however, another animal pushed it, this indicates that the owner was negligent and should have prevented this happening. Therefore, in such a case, the owner pays for what his animal damaged, since the owner of the garden can say to the owner of the animal: You should have led your animals across one by one, so that they would not be able to push each other.

אָמַר רַב כָּהֲנָא: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא בְּאוֹתָהּ עֲרוּגָה, אֲבָל מֵעֲרוּגָה לַעֲרוּגָה – מְשַׁלֶּמֶת מַה שֶּׁהִזִּיקָה. וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: אֲפִילּוּ מֵעֲרוּגָה לַעֲרוּגָה, וַאֲפִילּוּ כׇּל הַיּוֹם כּוּלּוֹ – עַד שֶׁתֵּצֵא וְתַחֲזוֹר לְדַעַת.

Rav Kahana says: They taught only that the owner pays for the benefit that it derives in the same garden bed into which it fell, but if it went from one garden bed to another garden bed and ate from that one, the owner pays for what it damaged. And Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Even if the animal goes from one garden bed to another garden bed and eats, and even if the animal continues going from one bed to another and eating for the entire day, the owner pays only for the benefit that the animal derived and not for what it damaged, unless it leaves the garden entirely and returns with the owner’s knowledge.

אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: לָא תֵּימָא עַד שֶׁתֵּצֵא לְדַעַת וְתַחֲזוֹר לְדַעַת, אֶלָּא כֵּיוָן שֶׁיָּצְתָה לְדַעַת – אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁחָזְרָה שֶׁלֹּא לְדַעַת. מַאי טַעְמָא? דַּאֲמַר לֵיהּ: כֵּיוָן דְּיָלְפָא, כֹּל אֵימַת דְּמִשְׁתַּמְטָא – לְהָתָם רָהֲטָא.

Rav Pappa said, explaining Rabbi Yoḥanan’s statement: Do not say this means: Unless the animal leaves with the owner’s knowledge and returns with his knowledge; rather, once it leaves the garden with the owner’s knowledge, even if it returned without his knowledge, the owner is liable to pay for what it damaged. What is the reason for this? It is that the owner of the garden can say to the owner of the animal: Since the animal has now learned that the garden is there with food to eat, every time it strays it will run to there.

יָרְדָה כְּדַרְכָּהּ וְהִזִּיקָה – מְשַׁלֶּמֶת מַה שֶּׁהִזִּיקָה. בָּעֵי רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה: יָרְדָה כְּדַרְכָּהּ וְהִזִּיקָה בְּמֵי לֵידָה, מַהוּ?

§ The mishna teaches: If the animal descended into the garden in its usual manner and caused damage there, the owner pays for what it damaged. Rabbi Yirmeya asks: If the animal descended in its usual manner and gave birth to a calf there and damaged the produce with amniotic fluid, what is the halakha? Does the owner of the animal have to pay for this damage?

אַלִּיבָּא דְּמַאן דְּאָמַר תְּחִלָּתוֹ בִּפְשִׁיעָה וְסוֹפוֹ בְּאוֹנֶס חַיָּיב, לָא תִּיבְּעֵי לָךְ; כִּי תִּיבְּעֵי לָךְ – אַלִּיבָּא דְּמַאן דְּאָמַר תְּחִלָּתוֹ בִּפְשִׁיעָה וְסוֹפוֹ בְּאוֹנֶס פָּטוּר; מַאי?

The Gemara clarifies Rabbi Yirmeya’s question: Do not raise the dilemma in accordance with the opinion of the one who says that one is liable in a case of damage that is initially through negligence and ultimately by accident, since in this case the owner was negligent in allowing the animal to enter another person’s courtyard, although the actual causing of the damage was ultimately by accident. When should you raise this dilemma? Raise it in accordance with the opinion of the one who says that one is exempt in a case that is initially through negligence and ultimately by accident. What is the halakha in this case?

מִי אָמְרִינַן: כֵּיוָן דִּתְחִלָּתוֹ בִּפְשִׁיעָה וְסוֹפוֹ בְּאוֹנֶס – פָּטוּר; אוֹ דִלְמָא, הָכָא כּוּלַּהּ בִּפְשִׁיעָה הוּא – דְּכֵיוָן דְּקָא חָזֵי דִּקְרִיבָה לַהּ לְמֵילַד, אִיבְּעִי לֵיהּ לְנָטוֹרַהּ

The two sides of the question are as follows: Do we say that, since this case is initially through negligence and ultimately by accident, he is exempt from liability? Or perhaps here, in this case, it is entirely due to his negligence; since he saw that the animal was close to giving birth, he should have safeguarded it adequately

וּלְאִסְתַּמּוֹרֵי בְּגַוַּהּ? תֵּיקוּ.

and taken care of it, and he bears responsibility for failing to do so. The dilemma shall stand unresolved.

כֵּיצַד מְשַׁלֶּמֶת מַה שֶּׁהִזִּיקָה וְכוּ׳. מְנָא הָנֵי מִילֵּי?

§ The mishna teaches: How does the court appraise the value of the damage when the owner pays for what it damaged? The court appraises a large piece of land with an area required for sowing one se’a of seed [beit se’a] in that field, including the garden bed in which the damage took place, it appraises how much it was worth before the animal damaged it and how much is it worth now, and the owner must pay the difference. The Gemara asks: From where are these matters derived?

אָמַר רַב מַתְנָה, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״וּבִעֵר בִּשְׂדֵה אַחֵר״ – מְלַמֵּד שֶׁשָּׁמִין עַל גַּב שָׂדֶה אַחֵר.

Rav Mattana says: As the verse states: “And it feed in another field [uvi’er bisde aḥer]” (Exodus 22:4). This teaches that the court appraises the damage relative to another field, i.e., relative to the damaged field as a whole and not an appraisal of only the specific garden bed that was damaged.

הַאי ״וּבִעֵר בִּשְׂדֵה אַחֵר״ מִבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְאַפּוֹקֵי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים!

The Gemara asks: But this phrase: “Uvi’er bisde aḥer,” can be understood as meaning: “And it feed in another’s field,” and accordingly, is necessary to teach that the owner is not liable unless it was a field with an owner, to exclude damage caused by an animal in the public domain, for which the owner is not liable.

אִם כֵּן, לִכְתּוֹב רַחֲמָנָא ״וּבִעֵר בִּשְׂדֵה חֲבֵירוֹ״, אִי נָמֵי ״שְׂדֵה אַחֵר״! מַאי ״בִּשְׂדֵה אַחֵר״? שֶׁשָּׁמִין עַל גַּב שָׂדֶה אַחֵר.

The Gemara answers: If so, if this was the sole intention of the verse, let the Merciful One write in the Torah: And it feed in a field belonging to another [uvi’er bisde ḥaveiro], or alternatively, let it write: And it consume another field [sedeh aḥer].” What is conveyed by the particular expression: “In another field [bisde aḥer]”? It is to teach that the court appraises the damage relative to another field.

וְאֵימָא כּוּלֵּיהּ לְהָכִי הוּא דַּאֲתָא; לְאַפּוֹקֵי רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים מְנָלַן?

But why not say that this verse comes entirely for this purpose, i.e., to teach that the court appraises the damage relative to another field? And in that case, from where do we derive the exclusion of liability for damage by Eating in the public domain?

אִם כֵּן, לִכְתְּבֵיהּ רַחֲמָנָא גַּבֵּי תַשְׁלוּמִין – ״מֵיטַב שָׂדֵהוּ וּמֵיטַב כַּרְמוֹ יְשַׁלֵּם בִּשְׂדֵה אַחֵר״! לְמָה לִי דְּכַתְבֵיהּ רַחֲמָנָא גַּבֵּי ״וּבִעֵר״? שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ תַּרְתֵּי.

The Gemara answers: If it is so that the verse was referring solely to the method of appraising the damage, the Merciful One should have written this in the Torah in the context of payment, as follows: His best-quality field and the best quality of his vineyard he shall pay in another field (see Exodus 22:4), thereby adding the term: In another field, and, by extension, the directive concerning how the damage is appraised, to the verse discussing payment. Why do I need the Merciful One to write it in the context of the act of damaging, in the verse: “And it feed in another field”? Conclude two conclusions from it: The verse is referring to both the place where the damage occurred and the method by which the damage is appraised.

הֵיכִי שָׁיְימִינַן? אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא: סְאָה בְּשִׁשִּׁים סְאִין. רַבִּי יַנַּאי אָמַר: תַּרְקַב בְּשִׁשִּׁים תַּרְקַבִּים. חִזְקִיָּה אָמַר: קֶלַח בְּשִׁשִּׁים קְלָחִים.

§ The Gemara asks: How do we, the court, appraise the value of the damage? Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina says: The court appraises the value of an area required for sowing one se’a of seed [beit se’a] relative to an area required for sowing sixty se’a of seed, and according to this calculation determines the value of the damage. Rabbi Yannai says: The court appraises each tarkav, equivalent to half a beit se’a, relative to an area of sixty tarkav. Ḥizkiyya says: The court appraises the value of each stalk eaten relative to sixty stalks.

מֵיתִיבִי: אָכְלָה קַב אוֹ קַבַּיִים – אֵין אוֹמְרִים תְּשַׁלֵּם דְּמֵיהֶן, אֶלָּא רוֹאִין אוֹתָהּ כְּאִילּוּ הִיא עֲרוּגָה קְטַנָּה, וּמְשַׁעֲרִים אוֹתָהּ. מַאי, לָאו בִּפְנֵי עַצְמָהּ?

The Gemara raises an objection from a baraita: If an animal ate one kav or two kav, the court does not say that the owner pays compensation according to their value, i.e., the value of the actual damage; rather, they view it as if it were a small garden bed and evaluate it accordingly. What, is it not that this means that the court evaluates that garden bed according to what it would cost if sold by itself, which contradicts all the previous explanations?

לָא, בְּשִׁשִּׁים.

The Gemara rejects this interpretation: No, it means that the court appraises the value in relation to an area sixty times greater.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: אֵין שָׁמִין קַב – מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּשְׁבִּיחוֹ, וְלֹא בֵּית כּוֹר – מִפְּנֵי שֶׁפּוֹגְמוֹ.

The Sages taught: When appraising the damage, the court does not appraise it based on an area of a beit kav, because doing so enhances his position, and they also do not appraise it relative to an area of a beit kor, equivalent to the area in which one can plant thirty se’a of seed, because this weakens his position.

מַאי קָאָמַר? אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא, הָכִי קָאָמַר: אֵין שָׁמִין קַב בְּשִׁשִּׁים קַבִּים – מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּשְׁבִּיחַ מַזִּיק, וְלֹא כּוֹר בְּשִׁשִּׁים כּוֹרִין – מִפְּנֵי שֶׁפּוֹגֵם מַזִּיק.

The Gemara asks: What is this baraita saying? Rav Pappa said: This is what the baraita is saying: The court does not appraise the value of one kav relative to an area of sixty kav, which, being too large for an individual but too small for a trader, is always sold in the market at a lower price, because that would enhance the position of the one liable for damage. Conversely, the court does not appraise the value of a kor relative to an area of sixty kor, an area so large that it is purchased only by a person with a specific need and therefore for a high price, because that would weaken the position of the one liable for damage.

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַב הוּנָא בַּר מָנוֹחַ: הַאי ״וְלֹא בֵּית כּוֹר״?! ״וְלֹא כּוֹר״ מִבְּעֵי לֵיהּ!

Rav Huna bar Manoaḥ objects to this: According to this interpretation, this term employed by the baraita: And they also do not appraise it relative to an area of a beit kor, is imprecise. According to the explanation of Rav Pappa, the baraita should have said: And they also do not appraise it relative to a kor, to parallel the term in the previous clause: A kav.

אֶלָּא אָמַר רַב הוּנָא בַּר מָנוֹחַ מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרַב אַחָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב אִיקָא, הָכִי קָתָנֵי: אֵין שָׁמִין קַב בִּפְנֵי עַצְמוֹ – מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמַּשְׁבִּיחַ נִיזָּק, וְלֹא קַב בְּבֵית כּוֹר – מִפְּנֵי שֶׁפּוֹגֵם נִיזָּק; אֶלָּא בְּשִׁשִּׁים.

Rather, Rav Huna bar Manoaḥ said in the name of Rav Aḥa, son of Rav Ika, that this is what the baraita is teaching: The court does not appraise a kav by itself, because that would enhance the position of the injured party, nor does the court appraise a kav as one part of a beit kor, because that would weaken the position of the injured party, since damage inside such a large area is insignificant. Rather, the court appraises the damage in relation to an area sixty times greater than the area that was damaged.

הָהוּא גַּבְרָא דְּקַץ קַשְׁבָּא מֵחַבְרֵיהּ. אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: לְדִידִי חֲזֵי לִי, וּתְלָתָא תָּאלָתָא בְּקִינָּא הֲווֹ קָיְימִי, וַהֲווֹ שָׁווּ מְאָה זוּזֵי. זִיל הַב לֵיהּ תְּלָתִין וּתְלָתָא וְתִילְתָּא. אָמַר: גַּבֵּי רֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא דְּדָאֵין דִּינָא דְּפָרְסָאָה, לְמָה לִי? אֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן, אֲמַר לֵיהּ: בְּשִׁשִּׁים.

§ The Gemara relates: There was a certain man who cut down a date palm [kashba] belonging to another. The latter came with the perpetrator for arbitration before the Exilarch. The Exilarch said to the perpetrator: I personally saw that place where the date palm was planted, and it actually contained three date palms [talata] standing together in a cluster, growing out of a single root, and they were worth altogether one hundred dinars. Consequently, since you, the perpetrator, cut down one of the three, go and give him thirty-three and one-third dinars, one third of the total value. The perpetrator rejected this ruling and said: Why do I need to be judged by the Exilarch, who rules according to Persian law? He came before Rav Naḥman for judgment in the same case, who said to him: The court appraises the damage in relation to an area sixty times greater than the damage caused. This amount is much less than thirty-three and one-third dinars.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא: אִם אָמְרוּ בְּנִזְקֵי מָמוֹנוֹ, יֹאמְרוּ בְּנִזְקֵי גוּפוֹ?!

Rava said to Rav Naḥman: If the Sages said that the court appraises damage caused by one’s property, such as his animal, relative to an area sixty times greater, would they also say that the court appraises damage relative to an area sixty times greater even for direct damage caused by one’s body?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרָבָא: בְּנִזְקֵי גוּפוֹ מַאי דַּעְתָּיךְ – דְּתַנְיָא: הַמַּבְכִּיר כַּרְמוֹ שֶׁל חֲבֵירוֹ סְמָדַר – רוֹאִין אוֹתוֹ כַּמָּה הָיָה יָפֶה קוֹדֶם לָכֵן, וְכַמָּה הוּא יָפֶה לְאַחַר מִכָּאן; וְאִילּוּ בְּשִׁשִּׁים לָא קָתָנֵי?

Abaye said to Rava: With regard to damage caused by one’s body, what is your opinion? Are you basing your opinion on the following, as it is taught in a baraita: If one destroys the vineyard of another while the grapes are budding [semadar], the court views how much the vineyard was worth before he destroyed it, and how much it is worth afterward. Abaye states the inference: Whereas, the method of appraising one part in sixty is not taught. Is the basis of your ruling the fact that in this baraita that discusses damage caused directly by a person, the method of appraising one part in sixty is not mentioned?

אַטּוּ גַּבֵּי בְהֶמְתּוֹ נָמֵי מִי לָא תַּנְיָא כִּי הַאי גַוְונָא?! דְּתַנְיָא: קָטְמָה נְטִיעָה – רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר, גּוֹזְרֵי גְזֵירוֹת שֶׁבִּירוּשָׁלַיִם אוֹמְרִים: נְטִיעָה בַּת שְׁנָתָהּ – שְׁתֵּי כֶּסֶף, בַּת שְׁתֵּי שָׁנִים – אַרְבָּעָה כֶּסֶף. אָכְלָה חֲזִיז – רַבִּי יוֹסֵי הַגְּלִילִי אוֹמֵר: נִידּוֹן בַּמְשׁוּיָּיר שֶׁבּוֹ, וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: רוֹאִין אוֹתָהּ כַּמָּה הָיְתָה יָפָה, וְכַמָּה הִיא יָפָה.

Abaye continued: Is that to say that with regard to damage caused by an animal it is not taught in a mishna or baraita without mentioning the method of appraising one part in sixty like this case? But this is not so, as it is taught in a baraita: If an animal broke down a sapling that had not yet borne fruit, Rabbi Yosei says: Those who issue decrees in Jerusalem say that the damages are determined based on a fixed formula: If the sapling was in its first year, the owner of the animal pays two pieces of silver; if the sapling was two years old, he pays four pieces of silver. If the animal ate unripe blades of grain used for pasture, Rabbi Yosei HaGelili says: It is judged according to what remains of it, i.e., the court waits until the rest of the field ripens and then appraises the value of what was previously eaten. And the Rabbis say: The court views how much the field was worth before he destroyed it, and how much it is worth now.