Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Summary

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

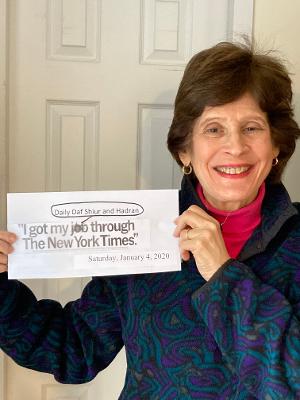

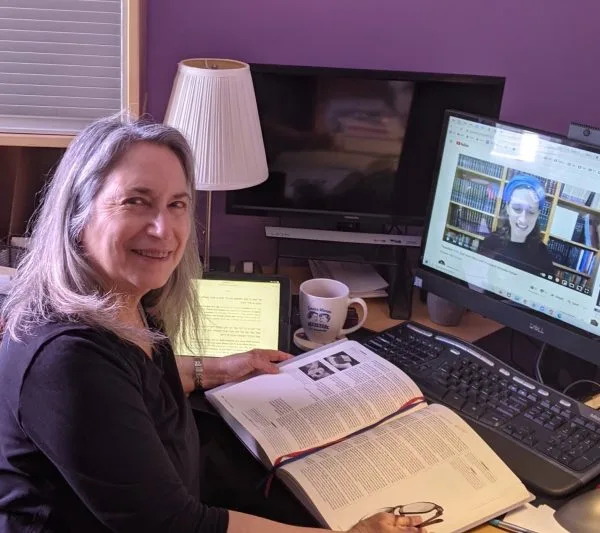

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Eruvin 83

תָּנָא: וַחֲצִי חֲצִי חֶצְיָהּ לְטַמֵּא טוּמְאַת אוֹכָלִין. וְתַנָּא דִּידַן מַאי טַעְמָא לָא תָּנֵי טוּמְאַת אוֹכָלִין? מִשּׁוּם דְּלָא שָׁווּ שִׁיעוּרַיְיהוּ לַהֲדָדֵי.

A Sage taught in the Tosefta: And half of one half of its half, one-eighth of this loaf, is the minimum measure of food that contracts the ritual impurity of foods. The Gemara asks: And our tanna, in the mishna, for what reason did he did not teach the measure of the impurity of foods? The Gemara answers: He did not state this halakha because their measures are not precisely identical. The measure for the impurity of foods is not exactly half the amount of ritually impure food that disqualifies one from eating teruma.

דְּתַנְיָא: כַּמָּה שִׁיעוּר חֲצִי פְרָס? שְׁתֵּי בֵיצִים חָסֵר קִימְעָא, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יְהוּדָה. רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: שְׁתֵּי בֵיצִים שׂוֹחֲקוֹת. שִׁיעֵר רַבִּי, שְׁתֵּי בֵיצִים וָעוֹד. כַּמָּה וָעוֹד? אֶחָד מֵעֶשְׂרִים בַּבֵּיצָה.

As it was taught in a baraita: How much is half a peras? Two eggs minus a little; this is the statement of Rabbi Yehuda. Rabbi Yosei says: Two large eggs, slightly larger ones than average. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi measured the amount of half a peras after calculating the number of kav in the se’a brought before him, and found it to be a little more than two eggs. The tanna asks: How much is this little more? One-twentieth of an egg.

וְאִילּוּ גַּבֵּי טוּמְאַת אוֹכָלִין תַּנְיָא: רַבִּי נָתָן וְרַבִּי דּוֹסָא אָמְרוּ: כְּבֵיצָה שֶׁאָמְרוּ כָּמוֹהָ וְכִקְלִיפָּתָהּ, וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: כָּמוֹהָ בְּלֹא קְלִיפָּתָהּ.

In contrast, concerning the impurity of foods, it was taught in a baraita: Rabbi Natan and Rabbi Dosa said that the measure of an egg-bulk, which the Sages said is the amount that contracts the impurity of foods, is equivalent to it, i.e., the egg, and its shell. And the Rabbis say: It is equivalent to it without its shell. These amounts are not precisely half of any of the measurements given for half a peras.

אָמַר רַפְרָם בַּר פָּפָּא אָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: זוֹ דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יְהוּדָה וְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי. אֲבָל חֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: כְּבֵיצָה וּמֶחֱצָה שׂוֹחֲקוֹת. וּמַאן חֲכָמִים — רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן בֶּן בְּרוֹקָה.

As for the issue itself, Rafram bar Pappa said that Rav Ḥisda said: This baraita that clarifies the measure of half a peras is in accordance with the statements of Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Yosei, a measure that is identical to that of Rabbi Shimon in the mishna. But the Rabbis say: One and one half large egg-bulks. And who are these Rabbis? Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Beroka.

פְּשִׁיטָא! שׂוֹחֲקוֹת אֲתָא לְאַשְׁמוֹעִינַן.

The Gemara registers surprise: This is obvious, as Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Beroka maintains that half a loaf is three egg-bulks, half of which is an egg-bulk and one half. The Gemara explains: The novel aspect of this teaching is not the amount itself; rather, he came to teach us that the measurement is performed with large eggs.

כִּי אֲתָא רַב דִּימִי, אָמַר: שִׁיגֵּר בּוֹנְיוֹס לְרַבִּי מוֹדְיָא דְקוֹנְדֵּיס דְּמִן נְאוּסָא, וְשִׁיעֵר רַבִּי מָאתַן וּשְׁבַע עֶשְׂרֵה בֵּיעִין.

The Gemara relates that when Rav Dimi came from Eretz Yisrael to Babylonia, he said: A person named Bonyos sent Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi a measure [modya] of a se’a from a place called Na’usa, where they had a tradition that it was an ancient and accurate measure (Ritva). And Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi measured it and found it contained 217 eggs.

הָא סְאָה דְּהֵיכָא? אִי דְּמִדְבָּרִית, מֵאָה אַרְבָּעִים וְאַרְבַּע הָוְיָא!

The Gemara asks: This se’a, from where is it, i.e., on what measure is it based? If it is based on the wilderness se’a, the standard measure used by Moses in the wilderness, which is the basis for all the Torah’s measurements of volume, the difficulty is that a se’a is composed of six kav, where each kav is equivalent to four log and each log is equivalent to six egg-bulks. This means that a se’a is equivalent to a total of 144 egg-bulks.

וְאִי דִּירוּשַׁלְמִית, מֵאָה שִׁבְעִים וְשָׁלֹשׁ הָוְיָא!

And if it is the Jerusalem se’a, then the se’a is only 173 egg-bulks, as they enlarged the measures in Jerusalem by adding a fifth to the measures of the wilderness.

וְאִי דְּצִיפּוֹרִית, מָאתַיִם וְשֶׁבַע הָוְיָין!

And if it is a se’a of Tzippori, as the measures were once again increased in Tzippori, where another fifth was added to the Jerusalem measure, the se’a is 207 egg-bulks. The se’a measured by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi does not correspond to any of these measures of a se’a.

לְעוֹלָם דְּצִיפּוֹרִית, אַיְיתִי חַלְּתָא שְׁדִי עֲלַיְיהוּ.

The Gemara answers: Actually, this measure is based on the se’a of Tzippori, but you must bring the amount of the ḥalla given to a priest, and add it to them. That is to say, although this measure is slightly larger than a se’a, if it is used for flour and you deduct the amount due as ḥalla, you are left with exactly one se’a, or 207 egg-bulks.

חַלְּתָא כַּמָּה הָוְיָין? תַּמְנֵי, אַכַּתִּי בָּצַר לֵיהּ!

The Gemara raises an objection: The amount of ḥalla, how many egg-bulks is it? Approximately eight egg-bulks, one-twenty-fourth of 207. Yet in that case, it remains less than 217 egg-bulks, for even if we were to add another eight egg-bulks for ḥalla to the 207 egg-bulks, we would have only 215 egg-bulks, almost 216 to be more precise, which is still less than 217.

אֶלָּא אַיְיתִי וְעוֹדוֹת דְּרַבִּי שְׁדִי עֲלַיְיהוּ.

Rather, you must bring the excess amounts of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, the little more he included in his measure, and add these to them. In Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s calculations, he did not factor in the ḥalla that had to be separated. Instead, the egg-bulks he used to measure the se’a were small egg-bulks. Consequently, one-twentieth of an egg-bulk must be added for each egg-bulk. Since one-twentieth of 207 egg-bulks is roughly ten, the total amount equals 217 egg-bulks.

אִי הָכִי, הָוֵי לֵיהּ טְפֵי! כֵּיוָן דְּלָא הָוֵי כְּבֵיצָה, לָא חָשֵׁיב לֵיהּ.

The Gemara raises an objection: If so, it is still slightly more than 217 egg-bulks, by seven-twentieths of an egg-bulk, to be precise. The Gemara answers: Since it is not more than 217 egg-bulks by a whole egg, he did not count it.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן סְאָה יְרוּשַׁלְמִית יְתֵירָה עַל מִדְבָּרִית שְׁתוּת. וְשֶׁל צִיפּוֹרִית יְתֵירָה עַל יְרוּשַׁלְמִית שְׁתוּת. נִמְצֵאת שֶׁל צִיפּוֹרִית יְתֵירָה עַל מִדְבָּרִית שְׁלִישׁ.

The Sages taught in a baraita: A Jerusalem se’a is larger than a wilderness se’a by one-sixth, and that of Tzippori is larger than a Jerusalem se’a by one-sixth. Consequently, a se’a of Tzippori is larger than a wilderness se’a by one-third.

שְׁלִישׁ דְּמַאן? אִילֵּימָא שְׁלִישׁ דְּמִדְבָּרִית, מִכְּדִי שְׁלִישׁ דְּמִדְבָּרִית כַּמָּה הָוֵי — אַרְבְּעִין וּתְמָנְיָא, וְאִילּוּ עוּדְפָּא, שִׁיתִּין וּתְלָת.

The Gemara inquires: One-third of which measurement? If you say it means one-third of a wilderness se’a, now you must consider: One-third of a wilderness se’a, how much is it? Forty-eight egg-bulks, and yet the difference between the wilderness se’a and the Tzippori se’a is sixty-three egg-bulks. As stated above, a Tzippori se’a is 207 egg-bulks, whereas a wilderness se’a is only 144 egg-bulks.

וְאֶלָּא שְׁלִישׁ דִּירוּשַׁלְמִית: שְׁלִישׁ דִּידַהּ כַּמָּה הָוֵי — חַמְשִׁין וּתְמָנְיָא נְכֵי תִּילְתָּא, וְאִילּוּ עוּדְפָּא, שִׁתִּין וּתְלָת. וְאֶלָּא דְּצִיפּוֹרִי: שְׁלִישׁ דִּידַהּ כַּמָּה הָוֵי — שִׁבְעִין נְכֵי חֲדָא, וְאִילּוּ עוּדְפָּא, שִׁשִּׁים וְשָׁלֹשׁ.

But rather, this one-third mentioned in the baraita is referring to one-third of a Jerusalem se’a, which is 173 egg-bulks, as stated above. The Gemara again examines the calculation: One-third of that se’a, how much is it? Fifty-eight less one-third, and yet the difference between the wilderness and the Tzippori se’a is sixty-three. Rather, you must say that it is referring to one-third of a Tzippori se’a. One-third of that se’a, how much is it? Seventy less one-third, and yet the difference between the wilderness se’a and the Tzippori se’a is sixty-three egg-bulks. The difference between the measures is not exactly one-third according to any of the known se’a measurements.

אֶלָּא אָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה, הָכִי קָאָמַר: נִמְצֵאת סְאָה שֶׁל צִיפּוֹרִי יְתֵירָה עַל מִדְבָּרִית קָרוֹב לִשְׁלִישׁ שֶׁלָּהּ. וּשְׁלִישׁ שֶׁלָּהּ קָרוֹב לְמֶחֱצָה דְּמִדְבָּרִית.

Rather, Rabbi Yirmeya said that this is what the tanna is saying: Consequently, a se’a of Tzippori is larger than a wilderness se’a by sixty-three egg-bulks, which is close to one-third of a Tzippori se’a of sixty-nine egg-bulks. And one-third of it, sixty-nine egg-bulks, is close to half of a wilderness se’a of seventy-two egg-bulks.

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רָבִינָא: מִידֵּי ״קָרוֹב״ ״קָרוֹב״ קָתָנֵי? אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבִינָא, הָכִי קָאָמַר: נִמְצֵאת שְׁלִישׁ שֶׁל צִיפּוֹרִי בִּוְעוֹדָיוֹת שֶׁל רַבִּי יְתֵירָה עַל מֶחֱצָה שֶׁל מִדְבָּרִית שְׁלִישׁ בֵּיצָה.

Ravina raised an objection to the opinion of Rabbi Yirmeya: Does the baraita state either: Close to one-third of a Tzippori se’a or: Close to half of a wilderness se’a? The wording of the baraita indicates an exact amount. Rather, Ravina said that this is what the tanna is saying: Consequently, one-third of a Tzippori se’a together with the excess amounts of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi is greater than half of a wilderness se’a of seventy-two egg-bulks by only one-third of an egg. In other words, a Tzippori se’a of 207 egg-bulks added to the excess amounts of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi of one-twentieth of an egg-bulk for each egg-bulk amounts to a total of 217 egg-bulks, one-third of which is seventy-two and one-third egg-bulks.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״רֵאשִׁית עֲרִיסוֹתֵיכֶם״,

Our Sages taught a baraita: The verse states: “You shall set apart a cake of the first of your dough as a gift; like the gift of the threshing floor, so shall you set it apart” (Numbers 15:20).

כְּדֵי עִיסּוֹתֵיכֶם, וְכַמָּה עִיסּוֹתֵיכֶם? כְּדֵי עִיסַּת הַמִּדְבָּר. וְכַמָּה עִיסַּת הַמִּדְבָּר?

What is the quantity of dough from which ḥalla must be separated? The amount of “your dough.” And how much is “your dough”? This amount is left unspecified by the verse. The Gemara answers: It is as the amount of the dough of the wilderness. The Gemara again asks: And how much is the dough of the wilderness?

דִּכְתִיב: ״וְהָעוֹמֶר עֲשִׂירִית הָאֵיפָה הוּא״. מִכָּאן אָמְרוּ, שִׁבְעָה רְבָעִים קֶמַח וָעוֹד חַיֶּיבֶת בְּחַלָּה, שֶׁהֵן שִׁשָּׁה שֶׁל יְרוּשַׁלְמִית, שֶׁהֵן חֲמִשָּׁה שֶׁל צִיפּוֹרִי.

The Gemara responds: The Torah states that the manna, the dough of the wilderness, was “an omer a head” (Exodus 16:16). A later verse elaborates on that measure, as it is written: “And an omer is the tenth part of an eifa” (Exodus 16:36). An eifa is three se’a, which are eighteen kav or seventy-two log. An omer is one-tenth of this measure. From here, this calculation, Sages said that dough prepared from seven quarters of a kav of flour and more is obligated in ḥalla. This is equal to six quarter-kav of the Jerusalem measure, which is five quarter-kav of the Tzippori measure.

מִכָּאן אָמְרוּ: הָאוֹכֵל כְּמִדָּה זוֹ — הֲרֵי זֶה בָּרִיא וּמְבוֹרָךְ. יָתֵר עַל כֵּן — רַעַבְתָן. פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן — מְקוּלְקָל בְּמֵעָיו.

From here the Sages also said: One who eats roughly this amount each day, is healthy, as he is able to eat a proper meal; and he is also blessed, as he is not a glutton who requires more. One who eats more than this is a glutton, while one who eats less than this has damaged bowels and must see to his health.

מַתְנִי׳ אַנְשֵׁי חָצֵר וְאַנְשֵׁי מִרְפֶּסֶת שֶׁשָּׁכְחוּ וְלֹא עֵירְבוּ, כׇּל שֶׁגָּבוֹהַּ עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים — לְמִרְפֶּסֶת. פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן — לֶחָצֵר.

MISHNA: If both the residents of houses that open directly into a courtyard and the residents of apartments that open onto a balcony from which stairs lead down to that courtyard forgot and did not establish an eiruv between them, anything in the courtyard that is ten handbreadths high, e.g., a mound or a post, is part of the balcony. The residents of the apartments open to the balcony may transfer objects to and from their apartments onto the mound or post. Any post or mound that is lower than this height is part of the courtyard.

חוּלְיַית הַבּוֹר וְהַסֶּלַע, גְּבוֹהִים עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים — לַמִּרְפֶּסֶת, פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן — לֶחָצֵר.

A similar halakha applies to an embankment that surrounds a cistern or a rock: If the embankments that surround a cistern or rock are ten handbreadths high, they belong to the balcony; if they are lower than this, they may be used only by the inhabitants of the courtyard.

בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — בִּסְמוּכָה, אֲבָל בְּמוּפְלֶגֶת — אֲפִילּוּ גָּבוֹהַּ עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים — לֶחָצֵר. וְאֵיזוֹ הִיא סְמוּכָה — כׇּל שֶׁאֵינָהּ רְחוֹקָה אַרְבָּעָה טְפָחִים.

In what case are these matters, the halakha that anything higher than ten handbreadths belongs to the balcony, stated? When the mound or embankment is near the balcony. But in a case where the embankment or mound is distant from it, even if it is ten handbreadths high, the right to use the embankment or mound goes to the members of the courtyard. And what is considered near? Anything that is not four handbreadths removed from the balcony.

גְּמָ׳ פְּשִׁיטָא, לָזֶה בְּפֶתַח וְלָזֶה בְּפֶתַח — הַיְינוּ חַלּוֹן שֶׁבֵּין שְׁתֵּי חֲצֵירוֹת.

GEMARA: The Gemara comments: It is obvious that if the residents of two courtyards established separate eiruvin, and the residents of both courtyards have convenient access to a certain area, the residents of this courtyard through an entrance, and the residents of that courtyard through another entrance, this is similar to the case of a window between two courtyards. If the residents did not establish a joint eiruv, the use of this window is prohibited to the residents of both courtyards.

לָזֶה בִּזְרִיקָה וְלָזֶה בִּזְרִיקָה — הַיְינוּ כּוֹתֶל שֶׁבֵּין שְׁתֵּי חֲצֵירוֹת. לָזֶה בְּשִׁלְשׁוּל וְלָזֶה בְּשִׁלְשׁוּל — הַיְינוּ חָרִיץ שֶׁבֵּין שְׁתֵּי חֲצֵירוֹת.

It is similarly obvious that if a place can be used by the residents of this courtyard only by throwing an object onto it and by the residents of that courtyard only by throwing, but it cannot be conveniently used by either set of residents, then this is equivalent to the case of a wall between two courtyards. If there is a wall between two courtyards, it may not be used by either courtyard. Likewise, if a place can be used by the residents of this courtyard only by lowering an object down to it and by the residents of that courtyard by a similar act of lowering, this is comparable to the halakha of a ditch between two courtyards, which may not be used by the residents of either courtyard.

לָזֶה בְּפֶתַח וְלָזֶה בִּזְרִיקָה — הַיְינוּ דְּרַבָּה בַּר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן. לָזֶה בְּפֶתַח וְלָזֶה בְּשִׁלְשׁוּל — הַיְינוּ דְּרַב שֵׁיזְבִי אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן.

It is likewise obvious that in a place that can be conveniently used by the residents of this courtyard through an entrance but can be used by the residents of that courtyard only by throwing an object onto it, this is governed by the ruling of Rabba bar Rav Huna, who said that Rav Naḥman said: This place may be used only by those who have access to the area by way of an entrance. Likewise, a place that can be conveniently used by the residents of this courtyard through an entrance but can be used by the residents of that courtyard only by lowering an object down to it, this is governed by the ruling of Rav Sheizvi, who said that Rav Naḥman said: This place may be used only by those who have convenient access to it.

לָזֶה בְּשִׁלְשׁוּל וְלָזֶה בִּזְרִיקָה, מַאי?

The ruling in each of the aforementioned cases is clear. What is the halakha concerning a place that can be used by the residents of this courtyard only by lowering an object down to it and by the residents of that courtyard only by throwing an object on top of it? In other words, if an area is lower than one courtyard but higher than the other, so that neither set of residents has convenient access to it, which of them is entitled to use it?

אָמַר רַב: שְׁנֵיהֶן אֲסוּרִין. וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר: נוֹתְנִין אוֹתוֹ לָזֶה שֶׁבְּשִׁלְשׁוּל. שֶׁלָּזֶה תַּשְׁמִישׁוֹ בְּנַחַת, וְלָזֶה תַּשְׁמִישׁוֹ בְּקָשֶׁה, וְכׇל דָּבָר שֶׁתַּשְׁמִישׁוֹ לָזֶה בְּנַחַת וְלָזֶה בְּקָשֶׁה — נוֹתְנִים אוֹתוֹ לָזֶה שֶׁתַּשְׁמִישׁוֹ בְּנַחַת.

Rav said: It is prohibited for both sets of residents to use it. As the use of the area is equally inconvenient to the residents of both courtyards, they retain equal rights to it and render it prohibited for the other group to use. And Shmuel said: The use of the area is granted to those who can reach it by lowering, as it is relatively easy for them to lower objects to it, and therefore its use is more convenient; whereas for the others, who must throw onto it, its use is more demanding. And there is a principle concerning Shabbat: Anything whose use is convenient for one party and more demanding for another party, one provides it to that one whose use of it is convenient.

תְּנַן: אַנְשֵׁי חָצֵר וְאַנְשֵׁי מִרְפֶּסֶת שֶׁשָּׁכְחוּ וְלֹא עֵירְבוּ, כָּל שֶׁגָּבוֹהַּ עֲשָׂרָה טְפָחִים — לַמִּרְפֶּסֶת, פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן — לֶחָצֵר.

In order to decide between these two opinions, the Gemara attempts to adduce a proof from the mishna: If the residents of houses that open directly into a courtyard and the residents of apartments that open onto a balcony from which stairs lead down to that courtyard forgot and did not establish an eiruv between them, anything in the courtyard that is ten handbreadths high belongs to the balcony, while anything that is less than this height belongs to the courtyard.

קָא סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ, מַאי מִרְפֶּסֶת —

The Gemara first explains: It might have entered your mind to say: What is the meaning of the balcony mentioned in the mishna?