Megillah 16 Part 2

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

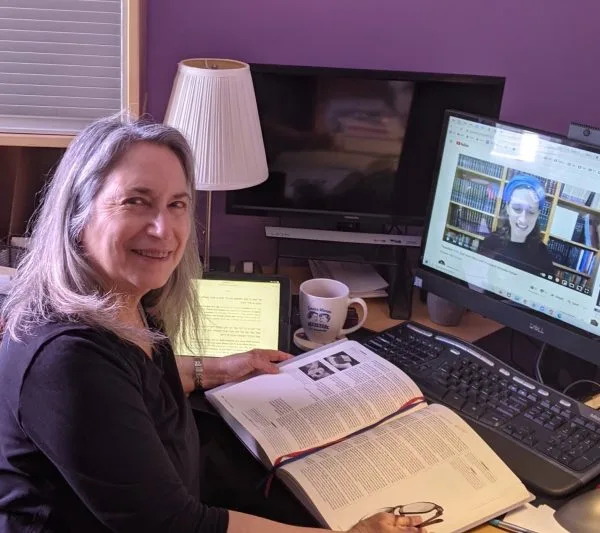

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Megillah 16 Part 2

מְגִילָּה נִקְרֵאת בְּאַחַד עָשָׂר, בִּשְׁנֵים עָשָׂר, בִּשְׁלֹשָׁה עָשָׂר, בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר, בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר. לֹא פָּחוֹת, וְלֹא יוֹתֵר. כְּרַכִּין הַמּוּקָּפִין חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן — קוֹרִין בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר, כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת — קוֹרִין בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר, אֶלָּא שֶׁהַכְּפָרִים מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה.

MISHNA: The Megilla is read on the eleventh, on the twelfth, on the thirteenth, on the fourteenth, or on the fifteenth of the month of Adar, not earlier and not later. The mishna explains the circumstances when the Megilla is read on each of these days. Cities [kerakin] that have been surrounded by a wall since the days of Joshua, son of Nun, read the Megilla on the fifteenth of Adar, whereas villages and large towns that have not been walled since the days of Joshua, son of Nun, read it on the fourteenth. However, the Sages instituted that the villages may advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Monday or Thursday, when the rabbinical courts are in session and the Torah is read publicly, and the villagers therefore come to the larger towns.

כֵּיצַד: חָל לִהְיוֹת אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר בַּשֵּׁנִי — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם, וּמוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה לְמָחָר. חָל לִהְיוֹת בַּשְּׁלִישִׁי אוֹ בָּרְבִיעִי — כְּפָרִים מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם, וּמוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה לְמָחָר.

How so? If the fourteenth of Adar occurs on Monday, the villages and large towns read it on that day, and the walled cities read it on the next day, the fifteenth. If the fourteenth occurs on Tuesday or Wednesday, the villages advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Monday, the twelfth or thirteenth of Adar; the large towns read it on that day, i.e., the fourteenth of Adar, and the walled cities read it on the next day, the fifteenth.

חָל לִהְיוֹת בַּחֲמִישִׁי — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם, וּמוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה לְמָחָר. חָל לִהְיוֹת עֶרֶב שַׁבָּת — כְּפָרִים מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת וּמוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם.

If the fourteenth occurs on Thursday, the villages and large towns read it on that day, the fourteenth, and the walled cities read it on the next day, the fifteenth. If the fourteenth occurs on Shabbat eve, the villages advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Thursday, the thirteenth of Adar; and the large towns and the walled cities read it on that day, i.e., the fourteenth of Adar. Even the walled cities read the Megilla on the fourteenth rather than on the fifteenth, as they do not read it on Shabbat.

חָל לִהְיוֹת בַּשַּׁבָּת — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת מַקְדִּימִין וְקוֹרִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, וּמוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה לְמָחָר. חָל לִהְיוֹת אַחַר הַשַּׁבָּת — כְּפָרִים מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם, וּמוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה לְמָחָר.

If the fourteenth occurs on Shabbat, both the villages and large towns advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Thursday, the twelfth of Adar; and the walled cities read it on the day after Purim, the fifteenth. If the fourteenth occurs on Sunday, the villages advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Thursday, the eleventh of Adar; and the large towns read it on that day, i.e., the fourteenth of Adar; and the walled cities read it on the next day, the fifteenth.

גְּמָ׳ מְגִילָּה נִקְרֵאת בְּאַחַד עָשָׂר. מְנָלַן? מְנָלַן?! כִּדְבָעֵינַן לְמֵימַר לְקַמַּן: חֲכָמִים הֵקֵילּוּ עַל הַכְּפָרִים לִהְיוֹת מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּסַפְּקוּ מַיִם וּמָזוֹן לַאֲחֵיהֶם שֶׁבַּכְּרַכִּים.

GEMARA: We learned in the mishna: The Megilla is read on the eleventh of Adar. The Gemara asks: From where do we derive this halakha? The Gemara expresses surprise at the question: What room is there to ask: From where do we derive this halakha? The reason is as we intend to say further on: The Sages were lenient with the villages and allowed them to advance their reading of the Megilla to the day of assembly, so that they would be free to supply water and food to their brethren in the cities on the day of Purim. Accordingly, the Megilla is read on the eleventh due to a rabbinic enactment.

אֲנַן הָכִי קָאָמְרִינַן: מִכְּדִי כּוּלְּהוּ אַנְשֵׁי כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה תַּקְּנִינְהוּ, דְּאִי סָלְקָא דַעְתָּךְ אַנְשֵׁי כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר וַחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר תַּקּוּן — אָתוּ רַבָּנַן וְעָקְרִי תַּקַּנְתָּא דְּתַקִּינוּ אַנְשֵׁי כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה? וְהָתְנַן: אֵין בֵּית דִּין יָכוֹל לְבַטֵּל דִּבְרֵי בֵּית דִּין חֲבֵירוֹ אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן גָּדוֹל מִמֶּנּוּ בְּחָכְמָה וּבְמִנְיָן.

The Gemara explains: This is what we said, i.e., this is what we meant when we asked the question: Now, all of these days when the Megilla may be read were enacted by the members of the Great Assembly when they established the holiday of Purim itself. As, if it enters your mind to say that the members of the Great Assembly enacted only the fourteenth and fifteenth as days for reading the Megilla, is it possible that the later Sages came and uprooted an ordinance that was enacted by the members of the Great Assembly? Didn’t we learn in a mishna (Eduyyot 1:5) that a rabbinical court cannot rescind the statements of another rabbinical court, unless it is superior to it in wisdom and in number? No subsequent court was ever greater than the members of the Great Assembly, so it would be impossible for another court to rescind the enactments of the members of the Great Assembly.

אֶלָּא פְּשִׁיטָא כּוּלְּהוּ אַנְשֵׁי כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה תַּקִּינוּ. הֵיכָא רְמִיזָא?

Rather, it is obvious that all these days were enacted by the members of the Great Assembly, and the question is: Where is the allusion to this in the Bible? The Megilla itself, which was approved by the members of the Great Assembly, mentions only the fourteenth and fifteenth of Adar.

אָמַר רַב שֶׁמֶן בַּר אַבָּא אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, אָמַר קְרָא: ״לְקַיֵּים אֵת יְמֵי הַפּוּרִים הָאֵלֶּה בִּזְמַנֵּיהֶם״, זְמַנִּים הַרְבֵּה תִּקְּנוּ לָהֶם.

Rav Shemen bar Abba said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: It is alluded to when the verse states: “To confirm these days of Purim in their times” (Esther 9:31). The phrase “in their times” indicates that they enacted many times for them and not only two days.

הַאי מִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ לְגוּפֵיהּ! אִם כֵּן לֵימָא קְרָא ״זְמַן״, מַאי ״זְמַנֵּיהֶם״ — זְמַנִּים טוּבָא.

The Gemara objects: This verse is necessary for its own purpose, to teach that the days of Purim must be observed at the proper times. The Gemara responds: If so, let the verse say: To confirm these days of Purim in its time. What is the significance of the term “their times,” in the plural? It indicates that many times were established for the reading of the Megilla.

וְאַכַּתִּי מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ: זְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה לֹא כִּזְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה! אִם כֵּן, לֵימָא קְרָא ״זְמַנָּם״, מַאי ״זְמַנֵּיהֶם״ — שָׁמְעַתְּ מִינַּהּ כּוּלְּהוּ.

The Gemara objects: But still, the plural term is necessary to indicate that the time of this walled city is not the same as the time of that unwalled town, i.e., Purim is celebrated on different days in different places. The Gemara answers: If so, let the verse say: Their time, indicating that each place celebrates Purim on its respective day. What is the significance of the compound plural “their times”? Learn from this term that although the verse (Esther 9:21) specifies only two days, the Megilla may, at times, be read on all of the days enumerated in the mishna.

אֵימָא זְמַנִּים טוּבָא! ״זְמַנֵּיהֶם״ דּוּמְיָא דִּ״זְמַנָּם״: מָה ״זְמַנָּם״ תְּרֵי — אַף ״זְמַנֵּיהֶם״ תְּרֵי.

The Gemara asks: If so, say that the plural term indicates many times, and the Megilla may be read even earlier than the eleventh of Adar. The Gemara rejects this argument: The compound plural “their times,” should be understood as similar to the simple plural term, their time. Just as the term their time can be understood to refer to two days, indicating that each location reads the Megilla in its respective time on the fourteenth or the fifteenth of Adar, so too, “their times” should be understood as referring to only two additional days when the Megilla may be read.

וְאֵימָא תְּרֵיסַר וּתְלֵיסַר? כִּדְאָמַר רַב שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר יִצְחָק: שְׁלֹשָׁה עָשָׂר זְמַן קְהִילָּה לַכֹּל הִיא, וְלָא צְרִיךְ לְרַבּוֹיֵי, הָכָא נָמֵי: שְׁלֹשָׁה עָשָׂר זְמַן קְהִילָּה לַכֹּל הִיא, וְלָא צְרִיךְ לְרַבּוֹיֵי.

The Gemara asks: Say that these two added days are the twelfth and the thirteenth of Adar. How is it derived that the Megilla may be read on the eleventh as well? The Gemara answers: It is as Rav Shmuel bar Yitzḥak said in a different context: The thirteenth of Adar is a time of assembly for all, as it was on that day that the Jews assembled to fight their enemies, and the main miracle was performed on that day. Consequently, there is no need for a special derivation to include it as a day that is fit for reading the Megilla. Here too, since the thirteenth of Adar is a time of assembly for all, there is no need for a special derivation to include it among the days when the Megilla may be read.

וְאֵימָא שִׁיתְּסַר וְשִׁיבְסַר! ״וְלֹא יַעֲבוֹר״ כְּתִיב.

The Gemara objects: And say that the two additional days are the sixteenth and the seventeenth of Adar. The Gemara responds: It is written: “And it shall not pass” (Esther 9:27), indicating that the celebration of Purim is not delayed until a later date.

וְרַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי אָמַר, אָמַר קְרָא: ״כַּיָּמִים אֲשֶׁר נָחוּ בָהֶם הַיְּהוּדִים״. ״יָמִים״, ״כַּיָּמִים״ — לְרַבּוֹת אַחַד עָשָׂר וּשְׁנֵים עָשָׂר.

Having cited and discussed the opinion of Rav Shemen bar Abba, the Gemara cites another answer to the question of where the verses allude to the permissibility of reading the Megilla on the days enumerated in the mishna. And Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥmani said: These dates are alluded to when the verse states: “As the days on which the Jews rested from their enemies” (Esther 9:22). The term “days” is referring to the two days that are explicitly mentioned in the previous verse, i.e., the fourteenth and the fifteenth. The term “as the days” comes to include two additional days, i.e., the eleventh and twelfth of Adar.

וְאֵימָא תְּרֵיסַר וּתְלֵיסַר! אָמַר רַב שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר יִצְחָק: שְׁלֹשָׁה עָשָׂר זְמַן קְהִילָּה לַכֹּל הִיא, וְלָא צְרִיךְ לְרַבּוֹיֵי. וְאֵימָא שִׁיתְּסַר וְשִׁיבְסַר! ״וְלֹא יַעֲבוֹר״ כְּתִיב.

The Gemara asks: And say that the two additional days are the twelfth and thirteenth of Adar. How is it derived that the Megilla may be read on the eleventh as well? In answer to this question, Rav Shmuel bar Yitzḥak said: The thirteenth of Adar is a time of assembly for all, and there is no need for a special derivation to include it as a day fit for reading. The Gemara objects: Say that these additional days are the sixteenth and seventeenth of Adar. This suggestion is rejected: It is written: “And it shall not pass.”

רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי מַאי טַעְמָא לָא אָמַר מִ״בִּזְמַנֵּיהֶם״? ״זְמַן״ ״זְמַנָּם״ ״זְמַנֵּיהֶם״ לָא מַשְׁמַע לֵיהּ.

Since two derivations were offered for the same matter, the Gemara asks: What is the reason that Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥmani did not state that the days enumerated in the mishna are fit for reading the Megilla based upon the term “in their times,” in accordance with the opinion of Rav Shemen bar Abba? The Gemara answers: He does not learn anything from the distinction between the terms time, their time, and their times. Therefore, the verse indicates only that there are two days when the Megilla may be read.

וְרַב שֶׁמֶן בַּר אַבָּא מַאי טַעְמָא לָא אָמַר מִ״כַּיָּמִים״? אָמַר לָךְ: הָהוּא לְדוֹרוֹת הוּא דִּכְתִיב.

The Gemara asks: And what is the reason that Rav Shemen bar Abba did not state that the days enumerated in the mishna are fit for reading the Megilla based upon the term “as the days,” in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥmani? The Gemara answers: He could have said to you: That verse is written as a reference to future generations, and it indicates that just as the Jews rested on these days at that time, they shall rest and celebrate on these days for all generations.

אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: זוֹ דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא סְתִימְתָּאָה, דְּדָרֵישׁ ״זְמַן״ ״זְמַנָּם״ ״זְמַנֵּיהֶם״, אֲבָל חֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ.

§ With regard to the mishna’s ruling that the Megilla may be read on the day of assembly, Rabba bar bar Ḥana said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: This is the statement of Rabbi Akiva the unattributed. Most unattributed statements of tanna’im were formulated by Rabbi Akiva’s students and reflect his opinions. As, he derives halakhot based on the distinction that he draws between the terms time, their time, and their times. However, the Sages say: One may read the Megilla only in its designated time, i.e., the fourteenth of Adar.

מֵיתִיבִי, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֵימָתַי — בִּזְמַן שֶׁהַשָּׁנִים כְּתִיקְנָן וְיִשְׂרָאֵל שְׁרוּיִין עַל אַדְמָתָן, אֲבָל בִּזְמַן הַזֶּה, הוֹאִיל וּמִסְתַּכְּלִין בָּהּ — אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ.

The Gemara raises an objection based upon the following baraita. Rabbi Yehuda said: When is one permitted to read the Megilla from the eleventh to the fifteenth of Adar? One may read on these dates at a time when the years are established properly and the Jewish people dwell securely in their own land. However, nowadays, since people look to the reading of the Megilla and use it to calculate when Passover begins, one may read the Megilla only in its designated time, so as not to cause confusion with regard to the date of Passover, which is exactly one month from the day after Purim.

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַלִּיבָּא דְמַאן? אִילֵימָא אַלִּיבָּא דְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא — אֲפִילּוּ בִּזְמַן הַזֶּה אִיתָא לְהַאי תַּקַּנְתָּא!

The Gemara analyzes this baraita: In accordance with whose opinion did Rabbi Yehuda issue his ruling? If we say that it is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva, whose opinion is expressed in the mishna, there is a difficulty, as Rabbi Akiva holds that even nowadays this ordinance applies. According to Rabbi Akiva, it is permitted for residents of villages to read the Megilla on the day of assembly even nowadays, as he did not limit his ruling to times when the Jewish people dwell securely in their land.

אֶלָּא לָאו, אַלִּיבָּא דְרַבָּנַן, וּבִזְמַן שֶׁהַשָּׁנִים כְּתִיקְנָן וְיִשְׂרָאֵל שְׁרוּיִין עַל אַדְמָתָן — מִיהָא קָרֵינַן, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן תְּיוּבְתָּא.

Rather, is it not in accordance with the opinion of the Sages, who disagreed with Rabbi Akiva? And, nevertheless, at least when the years are established properly and the Jewish people dwell securely in their land, the Megilla is read even prior to the fourteenth, as the Sages disagree only about the halakha nowadays. This contradicts the statement of Rabbi Yoḥanan, who holds that the Megilla could never be read earlier than the fourteenth of Adar. The Gemara concludes: The refutation of the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan is indeed a conclusive refutation.

אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר בַּר חָנָה אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: זוֹ דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא סְתִימְתָּאָה, אֲבָל חֲכָמִים אָמְרוּ: בִּזְמַן הַזֶּה, הוֹאִיל וּמִסְתַּכְּלִין בָּהּ — אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ.

There are those who say a different version of the previous passage. Rabba bar bar Ḥana said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: This is the statement of Rabbi Akiva, the unattributed. However, the Sages said: Nowadays, since people look to the reading of the Megilla and use it to calculate when Passover begins, one may read the Megilla only in its designated time.

תַּנְיָא נָמֵי הָכִי, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֵימָתַי — בִּזְמַן שֶׁהַשָּׁנִים כְּתִיקְנָן וְיִשְׂרָאֵל שְׁרוּיִין עַל אַדְמָתָן, אֲבָל בִּזְמַן הַזֶּה, הוֹאִיל וּמִסְתַּכְּלִין בָּהּ — אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ.

The Gemara comments: This is also taught in a baraita: Rabbi Yehuda said: When is one permitted to read the Megilla from the eleventh to the fifteenth of Adar? At a time when the years are established properly and the Jewish people dwell securely in their own land. However, nowadays, since people look to the reading of the Megilla and use it to calculate when Passover begins, one may read the Megilla only in its designated time. According to this version, Rabbi Yehuda’s statement is consistent with the opinion of the Sages, as cited by Rabbi Yoḥanan.

רַב אָשֵׁי קַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַדְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה,

The Gemara adds: Rav Ashi poses a difficulty based on an apparent contradiction between the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda in the aforementioned baraita and a ruling cited in a mishna in the name of Rabbi Yehuda,

וּמוֹקֵים לַהּ לְבָרַיְיתָא כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה.

and he establishes the baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei bar Yehuda, rather than Rabbi Yehuda.

וּמִי אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה ״בִּזְמַן הַזֶּה, הוֹאִיל וּמִסְתַּכְּלִין בָּהּ — אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ״? וּרְמִינְהִי, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֵימָתַי — מָקוֹם שֶׁנִּכְנָסִין בַּשֵּׁנִי וּבַחֲמִישִׁי. אֲבָל מָקוֹם שֶׁאֵין נִכְנָסִין בַּשֵּׁנִי וּבַחֲמִישִׁי — אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ.

The Gemara explains the apparent contradiction: And did Rabbi Yehuda actually say that nowadays, since people look to the reading of the Megilla and use it to calculate when Passover begins, one may read the Megilla only in its designated time? The Gemara raises a contradiction from a mishna (5a): Rabbi Yehuda said: When is one permitted to read the Megilla from the eleventh of Adar? In a place where the villagers generally enter town on Monday and Thursday. However, in a place where they do not generally enter town on Monday and Thursday, one may read the Megilla only in its designated time, the fourteenth of Adar.

מְקוֹם שֶׁנִּכְנָסִין בַּשֵּׁנִי וּבַחֲמִישִׁי מִיהָא קָרֵינַן, וַאֲפִילּוּ בִּזְמַן הַזֶּה! וּמוֹקֵים לַהּ לְבָרַיְיתָא כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה.

The mishna indicates that, at least in a place where the villagers enter town on Monday and Thursday, one may read the Megilla from the eleventh of Adar even nowadays. And due to this contradiction, Rav Ashi establishes the baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei bar Yehuda.

וּמִשּׁוּם דְּקַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַדְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה מוֹקֵים לָהּ לְבָרַיְיתָא כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה?!

The Gemara expresses surprise: Because Rav Ashi poses a difficulty due to the apparent contradiction between the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda in the baraita and the opinion cited in a mishna in the name of Rabbi Yehuda, he establishes the baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei bar Yehuda? How could he have emended the text just because he had a difficulty that he did not know how to resolve?

רַב אָשֵׁי שְׁמִיעַ לֵיהּ דְּאִיכָּא דְּתָנֵי לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה וְאִיכָּא דְּתָנֵי לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה, וּמִדְּקַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה אַדְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה, אָמַר: מַאן דְּתָנֵי לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה — לָאו דַּוְוקָא, מַאן דְּתָנֵי לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר יְהוּדָה — דַּוְוקָא.

The Gemara explains: Rav Ashi heard that there were those who taught the baraita in the name of Rabbi Yehuda, and there were those who taught it in the name of Rabbi Yosei bar Yehuda. And since he had a difficulty with the apparent contradiction between one ruling of Rabbi Yehuda and another ruling of Rabbi Yehuda, he said: The one who taught it in the name of Rabbi Yehuda is not precise, whereas the one who taught it in the name of Rabbi Yosei bar Yehuda is precise, and in this way he eliminated the contradiction.

כְּרַכִּים הַמּוּקָּפִים חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן קוֹרִין בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר וְכוּ׳. מְנָהָנֵי מִילֵּי? אָמַר רָבָא, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״עַל כֵּן הַיְּהוּדִים הַפְּרָזִים הַיּוֹשְׁבִים בְּעָרֵי הַפְּרָזוֹת וְגוֹ׳״. מִדִּפְרָזִים בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר — מוּקָּפִין בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר.

§ We learned in the mishna: Cities that have been surrounded by a wall since the days of Joshua, son of Nun, read the Megilla on the fifteenth of Adar. The Gemara asks: From where are these matters derived, as they are not stated explicitly in the Megilla? Rava said: It is as the verse states: “Therefore the Jews of the villages, who dwell in the unwalled towns, make the fourteenth day of the month of Adar a day of gladness and feasting” (Esther 9:19). From the fact that the unwalled towns celebrate Purim on the fourteenth, it may be derived that the walled cities celebrate Purim on the fifteenth.

וְאֵימָא: פְּרָזִים בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר, מוּקָּפִין כְּלָל כְּלָל לָא! וְלָאו יִשְׂרָאֵל נִינְהוּ? וְעוֹד: ״מֵהוֹדּוּ וְעַד כּוּשׁ״ כְּתִיב.

The Gemara challenges this answer: Say that the unwalled towns celebrate Purim on the fourteenth, as indicated in the verse, and the walled cities do not celebrate it at all. The Gemara expresses astonishment: And are they not Jews? And furthermore: It is written that the kingdom of Ahasuerus was “from Hodu until Cush” (Esther 1:1), and the celebration of Purim was accepted in all of the countries of his kingdom (Esther 9:20–23).

וְאֵימָא: פְּרָזִים בְּאַרְבֵּיסַר מוּקָּפִין בְּאַרְבֵּיסַר וּבַחֲמֵיסַר, כְּדִכְתִיב: ״לִהְיוֹת עוֹשִׂים אֵת יוֹם אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר לְחֹדֶשׁ אֲדָר וְאֵת יוֹם חֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר [בּוֹ] בְּכׇל שָׁנָה״!

Rather, the following challenge may be raised: Say that the unwalled towns celebrate Purim on the fourteenth and the walled cities celebrate it on the fourteenth and on the fifteenth, as it is written: “That they should keep the fourteenth day of the month of Adar and the fifteenth day of the same, in every year” (Esther 9:21). This verse can be understood to mean that there are places where Purim is celebrated on both days.

אִי הֲוָה כְּתִב ״אֵת יוֹם אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר וַחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר״ — כִּדְקָאָמְרַתְּ, הַשְׁתָּא דִּכְתִיב ״אֵת יוֹם אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר וְאֵת יוֹם חֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר״ — אֲתָא ״אֵת״ וּפָסֵיק: הָנֵי בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר, וְהָנֵי בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר.

The Gemara rejects this argument: If it had been written in the verse: The fourteenth day and [ve] the fifteenth, it would be as you originally said. However, now that it is written: The fourteenth day and [ve’et] the fifteenth day, the particle et used here to denote the accusative comes and interrupts, indicating that the two days are distinct. Therefore, residents of these locations celebrate Purim on the fourteenth, and residents of those locations celebrate it on the fifteenth.

וְאֵימָא: פְּרָזִים — בְּאַרְבֵּיסַר, מוּקָּפִין — אִי בָּעוּ בְּאַרְבֵּיסַר, אִי בָּעוּ בַּחֲמֵיסַר! אָמַר קְרָא ״בִּזְמַנֵּיהֶם״, זְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה לֹא זְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה.

The Gemara suggests: Say that residents of unwalled towns celebrate Purim on the fourteenth, as stated in the verse, and with regard to residents of walled cities, if they wish they may celebrate it on the fourteenth, and if they wish they may celebrate it on the fifteenth. The Gemara responds: The verse states: “In their times” (Esther 9:31), indicating that the time when the residents of this place celebrate Purim is not the time when the residents of that place celebrate Purim.

וְאֵימָא בִּתְלֵיסַר! כְּשׁוּשָׁן.

The Gemara raises another challenge: Say that the walled cities should celebrate Purim on the thirteenth of Adar and not on the fifteenth. The Gemara answers: It stands to reason that the residents of walled cities, who do not celebrate Purim on the fourteenth, celebrate it as it is celebrated in Shushan, and it is explicitly stated that Purim was celebrated in Shushan on the fifteenth.

אַשְׁכְּחַן עֲשִׂיָּיה, זְכִירָה מְנָלַן? אָמַר קְרָא: ״וְהַיָּמִים הָאֵלֶּה נִזְכָּרִים וְנַעֲשִׂים״, אִיתַּקַּשׁ זְכִירָה לַעֲשִׂיָּיה.

The Gemara comments: We found a source for observing the holiday of Purim on the fourteenth of Adar in unwalled towns and on the fifteenth of Adar in walled cities; from where do we derive that remembering the story of Purim through the reading of the Megilla takes place on these days? The Gemara explains that the verse states: “That these days should be remembered and observed” (Esther 9:28), from which it is derived that remembering is compared to observing.

מַתְנִיתִין דְּלָא כִּי הַאי תַּנָּא. דְּתַנְיָא, רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה אוֹמֵר: כְּרַכִּין הַמּוּקָּפִין חוֹמָה מִימוֹת אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ קוֹרִין בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר.

§ The Gemara notes that the mishna is not in accordance with the opinion of this tanna, as it is taught in the Tosefta (1:1) that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa says: Cities that have been surrounded by a wall since the days of Ahasuerus read the Megilla on the fifteenth. According to the Tosefta, the status of walled cities is determined based upon whether they were walled in the time of Ahasuerus rather than the time of Joshua.

מַאי טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה? כִּי שׁוּשָׁן. מָה שׁוּשָׁן מוּקֶּפֶת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ וְקוֹרִין בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר — אַף כֹּל שֶׁמּוּקֶּפֶת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ קוֹרִין בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason for the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa? The Gemara explains that the Megilla is read on the fifteenth in cities that are like Shushan: Just as Shushan is a city that was surrounded by a wall since the days of Ahasuerus, and one reads the Megilla there on the fifteenth, so too every city that was walled since the days of Ahasuerus reads the Megilla on the fifteenth.

וְתַנָּא דִּידַן, מַאי טַעְמָא? יָלֵיף ״פְּרָזִי״ ״פְּרָזִי״. כְּתִיב הָכָא: ״עַל כֵּן הַיְּהוּדִים הַפְּרָזִים״, וּכְתִיב הָתָם: ״לְבַד מֵעָרֵי הַפְּרָזִי הַרְבֵּה מְאֹד״. מָה לְהַלָּן מוּקֶּפֶת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן, אַף כָּאן מוּקֶּפֶת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason for the opinion of the tanna of our mishna? The Gemara explains: It is derived through a verbal analogy between one instance of the word unwalled and another instance of the word unwalled. It is written here: “Therefore the Jews of the villages, who dwell in the unwalled towns” (Esther 9:19), and it is written there, in Moses’ statement to Joshua before the Jewish people entered Eretz Yisrael: “All these cities were fortified with high walls, gates and bars; besides unwalled towns, a great many” (Deuteronomy 3:5). Just as there, in Deuteronomy, the reference is to a city that was surrounded by a wall from the days of Joshua, son of Nun, so too here it is referring to a city that was surrounded by a wall from the days of Joshua, son of Nun.

בִּשְׁלָמָא רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה לָא אָמַר כְּתַנָּא דִּידַן — דְּלֵית לֵיהּ ״פְּרָזִי״ ״פְּרָזִי״, אֶלָּא תַּנָּא דִּידַן מַאי טַעְמָא לָא אָמַר כְּרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה?

The Gemara continues: Granted that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa did not state his explanation in accordance with the opinion of the tanna of our mishna because he did not hold that a verbal analogy can be established between one verse that employs the word unwalled and the other verse that employs the word unwalled. However, what is the reason that the tanna of our mishna did not state his explanation in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa?

מַאי טַעְמָא?! דְּהָא אִית לֵיהּ ״פְּרָזִי״ ״פְּרָזִי״! הָכִי קָאָמַר: אֶלָּא שׁוּשָׁן, דְּעָבְדָא כְּמַאן? לָא כִּפְרָזִים וְלָא כְּמוּקָּפִין!

The Gemara expresses astonishment: What is the reason? Isn’t it because he holds that it is derived from the verbal analogy between one usage of the word unwalled and the other usage of the word unwalled? The Gemara explains: This is what he said, i.e., this was the question: According to the tanna of our mishna, in accordance with whom does Shushan observe Purim? Shushan is not like the unwalled towns and not like the walled cities, as residents of Shushan celebrate Purim on the fifteenth, but the city was not surrounded by a wall since the days of Joshua.

אָמַר רָבָא, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ כְּדִי: שָׁאנֵי שׁוּשָׁן — הוֹאִיל וְנַעֲשָׂה בָּהּ נֵס.

Rava said, and some say it unattributed to any particular Sage: Shushan is different since the miracle occurred in it on the fifteenth of Adar, and therefore Purim is celebrated on that day. However, other cities are only considered walled cities and read the Megilla on the fifteenth of Adar if they were walled since the days of Joshua.

בִּשְׁלָמָא לְתַנָּא דִּידַן, הַיְינוּ דִּכְתִיב: ״מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה וְעִיר וָעִיר״. ״מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה״ — לְחַלֵּק בֵּין מוּקָּפִין חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן לְמוּקֶּפֶת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ.

The Gemara asks: Granted, according to the tanna of our mishna, this is the meaning of what is written: “And these days should be remembered and observed throughout every generation, every family, every province, and every city” (Esther 9:28). The phrase “every province [medina]” is expressed in the verse using repetition, so that it reads literally: Every province and province, and therefore contains a superfluous usage of the word province, is meant to distinguish between cities that were surrounded by a wall since the days of Joshua, son of Nun, where the Megilla is read on the fifteenth, and a city that was surrounded by a wall since the days of Ahasuerus, where the Megilla is read on the fourteenth.

״עִיר וְעִיר״ נָמֵי, לְחַלֵּק בֵּין שׁוּשָׁן לִשְׁאָר עֲיָירוֹת. אֶלָּא לְרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה, בִּשְׁלָמָא ״מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה״ — לְחַלֵּק בֵּין שׁוּשָׁן לִשְׁאָר עֲיָירוֹת, אֶלָּא ״עִיר וְעִיר״ לְמַאי אֲתָא?

The phrase “every city,” which is similarly expressed through repetition and contains a superfluous usage of the word city, also serves to distinguish between Shushan and other cities, as Purim is celebrated in Shushan on the fifteenth despite the fact that it was not walled since the time of Joshua. However, according to Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa, granted that the phrase “every province” comes to distinguish between Shushan and other cities that were not walled since the days of Ahasuerus; but what does the phrase “every city” come to teach?

אָמַר לְךָ רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן קׇרְחָה: וּלְתַנָּא דִּידַן מִי נִיחָא? כֵּיוָן דְּאִית לֵיהּ ״פְּרָזִי״ ״פְּרָזִי״ — ״מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה״ לְמָה לִי? אֶלָּא קְרָא לִדְרָשָׁה הוּא דַּאֲתָא, וְכִדְרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי הוּא דַּאֲתָא. דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: כְּרַךְ, וְכׇל הַסָּמוּךְ לוֹ, וְכׇל הַנִּרְאֶה עִמּוֹ — נִידּוֹן כִּכְרַךְ.

The Gemara explains that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korḥa could have said to you: According to the tanna of our mishna, does it work out well? Since he holds that it is derived from the verbal analogy between one verse that employs the word unwalled and the other verse that employs the word unwalled, why do I need the phrase “every province”? Rather, the verse comes for a midrashic exposition, and it comes to indicate that the halakha is in accordance with the ruling issued by Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi. As Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: A walled city, and all settlements adjacent to it, and all settlements that can be seen with it, i.e., that can be seen from the walled city, are considered like the walled city, and the Megilla is read there on the fifteenth.

עַד כַּמָּה? אָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא: כְּמֵחַמָּתָן לִטְבֶרְיָא — מִיל. וְלֵימָא מִיל! הָא קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן: דְּשִׁיעוּרָא דְמִיל כַּמָּה הָוֵי — כְּמֵחַמָּתָן לִטְבֶרְיָא.

The Gemara asks: Up to what distance is considered adjacent? Rabbi Yirmeya said, and some say that it was Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba who said: The limit is like the distance from the town of Ḥamtan to Tiberias, a mil. The Gemara asks: Let him say simply that the limit is a mil; why did he have to mention these places? The Gemara answers that the formulation of the answer teaches us this: How much distance comprises the measure of a mil? It is like the distance from Ḥamtan to Tiberias.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא: מַנְצְפַךְ — צוֹפִים אֲמָרוּם.

§ Having cited a statement of Rabbi Yirmeya, which some attribute to Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba, the Gemara cites other statements attributed to these Sages. Rabbi Yirmeya said, and some say that it was Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba who said: The Seers, i.e., the prophets, were the ones who said that the letters mem, nun, tzadi, peh, and kaf [mantzepakh], have a different form when they appear at the end of a word.

וְתִסְבְּרָא? וְהָכְתִיב: ״אֵלֶּה הַמִּצְוֹת״, שֶׁאֵין נָבִיא רַשַּׁאי לְחַדֵּשׁ דָּבָר מֵעַתָּה? וְעוֹד, הָאָמַר רַב חִסְדָּא: מֵם וְסָמֶךְ שֶׁבַּלּוּחוֹת

The Gemara asks: And how can you understand it that way? Isn’t it written: “These are the commandments that the Lord commanded Moses for the children of Israel in Mount Sinai” (Leviticus 27:34), which indicates that a prophet is not permitted to initiate or change any matter of halakha from now on? Consequently, how could the prophets establish new forms for the letters? And furthermore, didn’t Rav Ḥisda say: The letters mem and samekh in the tablets of the covenant given at Sinai

בְּנֵס הָיוּ עוֹמְדִין!

stood by way of a miracle?

אִין, מִהְוָה הֲווֹ, וְלָא הֲווֹ יָדְעִי הֵי בְּאֶמְצַע תֵּיבָה וְהֵי בְּסוֹף תֵּיבָה, וַאֲתוֹ צוֹפִים וְתַקִּינוּ פְּתוּחִין בְּאֶמְצַע תֵּיבָה וּסְתוּמִין בְּסוֹף תֵּיבָה.

The Gemara answers: Yes, two forms of these letters did exist at that time, but the people did not know which one of them was to be used in the middle of the word and which at the end of the word, and the Seers came and established that the open forms are to used be in the middle of the word and the closed forms at the end of the word.

סוֹף סוֹף ״אֵלֶּה הַמִּצְוֹת״, שֶׁאֵין נָבִיא עָתִיד לְחַדֵּשׁ דָּבָר מֵעַתָּה! אֶלָּא שְׁכָחוּם וְחָזְרוּ וְיִסְּדוּם.

The Gemara asks: Ultimately, however, doesn’t the phrase “these are the commandments” (Leviticus 27:34) indicate that a prophet is not permitted to initiate any matter of halakha from now on? Rather, it may be suggested that the final letters already existed at the time of the giving of the Torah, but over the course of time the people forgot them, and the prophets then came and reestablished them.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא: תַּרְגּוּם שֶׁל תּוֹרָה — אוּנְקְלוֹס הַגֵּר אֲמָרוֹ מִפִּי רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר וְרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ. תַּרְגּוּם שֶׁל נְבִיאִים — יוֹנָתָן בֶּן עוּזִּיאֵל אֲמָרוֹ מִפִּי חַגַּי זְכַרְיָה וּמַלְאָכִי, וְנִזְדַּעְזְעָה אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אַרְבַּע מֵאוֹת פַּרְסָה עַל אַרְבַּע מֵאוֹת פַּרְסָה. יָצְתָה בַּת קוֹל וְאָמְרָה: מִי הוּא זֶה שֶׁגִּילָּה סְתָרַיי לִבְנֵי אָדָם?

§ The Gemara cites another ruling of Rabbi Yirmeya or Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba. Rabbi Yirmeya said, and some say that it was Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba who said: The Aramaic translation of the Torah used in the synagogues was composed by Onkelos the convert based on the teachings of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua. The Aramaic translation of the Prophets was composed by Yonatan ben Uzziel based on a tradition going back to the last prophets, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. The Gemara relates that when Yonatan ben Uzziel wrote his translation, Eretz Yisrael quaked over an area of four hundred parasangs [parsa] by four hundred parasangs, and a Divine Voice emerged and said: Who is this who has revealed My secrets to mankind?

עָמַד יוֹנָתָן בֶּן עוּזִּיאֵל עַל רַגְלָיו וְאָמַר: אֲנִי הוּא שֶׁגִּלִּיתִי סְתָרֶיךָ לִבְנֵי אָדָם, גָּלוּי וְיָדוּעַ לְפָנֶיךָ שֶׁלֹּא לִכְבוֹדִי עָשִׂיתִי, וְלֹא לִכְבוֹד בֵּית אַבָּא, אֶלָּא לִכְבוֹדְךָ עָשִׂיתִי, שֶׁלֹּא יִרְבּוּ מַחֲלוֹקֹת בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל.

Yonatan ben Uzziel stood up on his feet and said: I am the one who has revealed Your secrets to mankind through my translation. However, it is revealed and known to You that I did this not for my own honor, and not for the honor of the house of my father, but rather it was for Your honor that I did this, so that discord not increase among the Jewish people. In the absence of an accepted translation, people will disagree about the meaning of obscure verses, but with a translation, the meaning will be clear.

וְעוֹד בִּיקֵּשׁ לְגַלּוֹת תַּרְגּוּם שֶׁל כְּתוּבִים, יָצְתָה בַּת קוֹל וְאָמְרָה לוֹ: דַּיֶּיךָּ! מַאי טַעְמָא — מִשּׁוּם דְּאִית בֵּיהּ קֵץ מָשִׁיחַ.

And Yonatan ben Uzziel also sought to reveal a translation of the Writings, but a Divine Voice emerged and said to him: It is enough for you that you translated the Prophets. The Gemara explains: What is the reason that he was denied permission to translate the Writings? Because it has in it a revelation of the end, when the Messiah will arrive. The end is foretold in a cryptic manner in the book of Daniel, and were the book of Daniel translated, the end would become manifestly revealed to all.

וְתַרְגּוּם שֶׁל תּוֹרָה, אוּנְקְלוֹס הַגֵּר אֲמָרוֹ? וְהָא אָמַר רַב אִיקָא בַּר אָבִין אָמַר רַב חֲנַנְאֵל אָמַר רַב: מַאי דִּכְתִיב: ״וַיִּקְרְאוּ בְּסֵפֶר תּוֹרַת הָאֱלֹהִים מְפוֹרָשׁ וְשׂוֹם שֶׂכֶל וַיָּבִינוּ בַּמִּקְרָא״. ״וַיִּקְרְאוּ בְּסֵפֶר תּוֹרַת הָאֱלֹהִים״ — זֶה מִקְרָא; ״מְפוֹרָשׁ״ — זֶה תַּרְגּוּם;

The Gemara asks: Was the translation of the Torah really composed by Onkelos the convert? Didn’t Rav Ika bar Avin say that Rav Ḥananel said that Rav said: What is the meaning of that which is written with respect to the days of Ezra: “And they read in the book, the Torah of God, distinctly; and they gave the sense, and they caused them to understand the reading” (Nehemiah 8:8)? The verse should be understood as follows: “And they read in the book, the Torah of God,” this is the scriptural text; “distinctly,” this is the translation, indicating that they immediately translated the text into Aramaic, as was customary during public Torah readings.

״וְשׂוֹם שֶׂכֶל״ — אֵלּוּ הַפְּסוּקִין; ״וַיָּבִינוּ בַּמִּקְרָא״ — אֵלּוּ פִּיסְקֵי טְעָמִים, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ — אֵלּוּ הַמָּסוֹרֹת! — שְׁכָחוּם וְחָזְרוּ וְיִסְּדוּם.

“And they gave the sense,” these are the divisions of the text into separate verses. “And they caused them to understand the reading,” these are the cantillation notes, through which the meaning of the text is further clarified. And some say that these are the Masoretic traditions with regard to the manner in which each word is to be written. This indicates that the Aramaic translation already existed at the beginning of the Second Temple period, well before the time of Onkelos. The Gemara answers: The ancient Aramaic translation was forgotten and then Onkelos came and reestablished it.

מַאי שְׁנָא דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא דְּלָא אִזְדַּעְזְעָה וְאַדִּנְבִיאֵי אִזְדַּעְזְעָה? דְּאוֹרָיְיתָא — מִיפָּרְשָׁא מִלְּתָא, דִּנְבִיאֵי — אִיכָּא מִילֵּי דְּמִיפָּרְשָׁן וְאִיכָּא מִילֵּי דִּמְסַתְּמָן, דִּכְתִיב: ״בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִגְדַּל הַמִּסְפֵּד בִּירוּשָׁלִַם כְּמִסְפַּד הֲדַדְרִימּוֹן בְּבִקְעַת מְגִידּוֹן״,

The Gemara asks: What is different about the translation of Prophets? Why is it that when Onkelos revealed the translation of the Torah, Eretz Yisrael did not quake, and when he revealed the translation of the Prophets, it quaked? The Gemara explains: The meaning of matters discussed in the Torah is clear, and therefore its Aramaic translation did not reveal the meaning of passages that had not been understood previously. Conversely, in the Prophets, there are matters that are clear and there are matters that are obscure, and the Aramaic translation revealed the meaning of obscure passages. The Gemara cites an example of an obscure verse that is clarified by the Aramaic translation: As it is written: “On that day shall there be a great mourning in Jerusalem, like the mourning of Hadadrimmon in the valley of Megiddon” (Zechariah 12:11).

וְאָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: אִלְמָלֵא תַּרְגּוּמָא דְּהַאי קְרָא — לָא יָדַעְנָא מַאי קָאָמַר: בְּיוֹמָא הַהוּא יִסְגֵּי מִסְפְּדָא בִּירוּשְׁלֶים כְּמִסְפְּדָא דְּאַחְאָב בַּר עָמְרִי דִּקְטַל יָתֵיהּ הֲדַדְרִימּוֹן בֶּן טַבְרִימּוֹן בְּרָמוֹת גִּלְעָד וּכְמִסְפְּדָא דְּיֹאשִׁיָּה בַּר אָמוֹן דִּקְטַל יָתֵיהּ פַּרְעֹה חֲגִירָא בְּבִקְעַת מְגִידּוֹ.

And with regard to that verse, Rav Yosef said: Were it not for the Aramaic translation of this verse, we would not have known what it is saying, as the Bible does not mention any incident involving Hadadrimmon in the valley of Megiddon. The Aramaic translation reads as follows: On that day, the mourning in Jerusalem will be as great as the mourning for Ahab, son of Omri, who was slain by Hadadrimmon, son of Tavrimon, in Ramoth-Gilead, and like the mourning for Josiah, son of Amon, who was slain by Pharaoh the lame in the valley of Megiddon. The translation clarifies that the verse is referring to two separate incidents of mourning, and thereby clarifies the meaning of this verse.

״וְרָאִיתִי אֲנִי דָנִיֵּאל לְבַדִּי אֶת הַמַּרְאָה וְהָאֲנָשִׁים אֲשֶׁר הָיוּ עִמִּי לֹא רָאוּ אֶת הַמַּרְאָה אֲבָל חֲרָדָה גְדוֹלָה נָפְלָה עֲלֵיהֶם וַיִּבְרְחוּ בְּהֵחָבֵא״. מַאן נִינְהוּ אֲנָשִׁים? אָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה וְאִיתֵּימָא רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא: זֶה חַגַּי זְכַרְיָה וּמַלְאָכִי.

§ The Gemara introduces another statement from the same line of tradition. The verse states: “And I, Daniel, alone saw the vision, for the men who were with me did not see the vision; but a great trembling fell upon them, so that they fled to hide themselves” (Daniel 10:7). Who were these men? The term “men” in the Bible indicates important people; who were they? Rabbi Yirmeya said, and some say that it was Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba who said: These are the prophets Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.

אִינְהוּ עֲדִיפִי מִינֵּיהּ, וְאִיהוּ עֲדִיף מִינַּיְיהוּ. אִינְהוּ עֲדִיפִי מִינֵּיהּ — דְּאִינְהוּ נְבִיאֵי וְאִיהוּ לָאו נָבִיא. אִיהוּ עֲדִיף מִינַּיְיהוּ — דְּאִיהוּ חֲזָא וְאִינְהוּ לָא חֲזוֹ.

The Gemara comments: In certain ways they, the prophets, were greater than him, Daniel, and in certain ways he, Daniel, was greater than them. They were greater than him, as they were prophets and he was not a prophet. Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi were sent to convey the word of God to the Jewish people, while Daniel was not sent to reveal his visions to others. In another way, however, he was greater than them, as he saw this vision, and they did not see this vision, indicating that his ability to perceive obscure and cryptic visions was greater than theirs.

וְכִי מֵאַחַר דְּלָא חֲזוֹ, מַאי טַעְמָא אִיבְּעִיתוּ? אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִינְהוּ לָא חֲזוֹ, מַזָּלַיְיהוּ חֲזוֹ.

The Gemara asks: Since they did not see the vision, what is the reason that they were frightened? The Gemara answers: Even though they did not see the vision, their guardian angels saw it, and therefore they sensed that there was something fearful there and they fled.

אָמַר רָבִינָא: שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: הַאי מַאן דְּמִיבְּעִית, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִיהוּ לָא חָזֵי, מַזָּלֵיהּ חָזֵי. מַאי תַּקַּנְתֵּיהּ? לִיקְרֵי קְרִיאַת שְׁמַע. וְאִי קָאֵים בִּמְקוֹם הַטִּנּוֹפֶת — לִינְשׁוֹף מִדּוּכְתֵּיהּ אַרְבַּע גַּרְמִידֵי. וְאִי לָא — לֵימָא הָכִי: ״עִיזָּא דְּבֵי טַבָּחֵי שַׁמִּינָא מִינַּאי״.

Ravina said: Learn from this incident that with regard to one who is frightened for no apparent reason, although he does not see anything menacing, his guardian angel sees it, and therefore he should take steps in order to escape the danger. The Gemara asks: What is his remedy? He should recite Shema, which will afford him protection. And if he is standing in a place of filth, where it is prohibited to recite verses from the Torah, he should distance himself four cubits from his current location in order to escape the danger. And if he is not able to do so, let him say the following incantation: The goat of the slaughterhouse is fatter than I am, and if a calamity must fall upon something, it should fall upon it.

וְהַשְׁתָּא דְּאָמְרַתְּ ״מְדִינָה וּמְדִינָה וְעִיר וָעִיר״ — לִדְרָשָׁה, ״מִשְׁפָּחָה וּמִשְׁפָּחָה״ לְמַאי אֲתָא? אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא: לְהָבִיא מִשְׁפְּחוֹת כְּהוּנָּה וּלְוִיָּה, שֶׁמְּבַטְּלִין עֲבוֹדָתָן וּבָאִין לִשְׁמוֹעַ מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה.

§ After this digression, the Gemara returns to the exposition of a verse cited above. Now that you have said that the phrases “every province” and “every city” appear for the purposes of midrashic exposition, for what exposition do the words “every family” appear in that same verse (Esther 9:28)? Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina said: These words come to include the priestly and Levitical families, and indicate that they cancel their service in the Temple and come to hear the reading of the Megilla.

דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: כֹּהֲנִים בַּעֲבוֹדָתָן וּלְוִיִּם בְּדוּכָנָן וְיִשְׂרָאֵל בְּמַעֲמָדָן — כּוּלָּן מְבַטְּלִין עֲבוֹדָתָן וּבָאִין לִשְׁמוֹעַ מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה.

As Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: The priests at their Temple service, the Levites on their platform in the Temple, where they sung the daily psalm, and the Israelites at their watches, i.e., the group of Israelites, corresponding to the priestly watches, who would come to Jerusalem and gather in other locations as representatives of the entire nation to observe or pray for the success of the Temple service, all cancel their service and come to hear the reading of the Megilla.

תַּנְיָא נָמֵי הָכִי: כֹּהֲנִים בַּעֲבוֹדָתָן, וּלְוִיִּם בְּדוּכָנָן, וְיִשְׂרָאֵל בְּמַעֲמָדָן — כּוּלָּן מְבַטְּלִין עֲבוֹדָתָן וּבָאִין לִשְׁמוֹעַ מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה. מִכָּאן סָמְכוּ שֶׁל בֵּית רַבִּי שֶׁמְּבַטְּלִין תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה וּבָאִין לִשְׁמוֹעַ מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה, קַל וָחוֹמֶר מֵעֲבוֹדָה: וּמָה עֲבוֹדָה שֶׁהִיא חֲמוּרָה — מְבַטְּלִינַן, תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן.

This is also taught in a baraita: The priests at their service, the Levites on the platform, and the Israelites at their watches, all cancel their service and come to hear the reading of the Megilla. The Sages of the house of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi relied upon the halakha stated here and determined that one cancels his Torah study and comes to hear the reading of the Megilla. They derived this principle by means of an a fortiori inference from the Temple service: Just as one who is engaged in performing service in the Temple, which is very important, cancels his service in order to hear the Megilla, is it not all the more so obvious that one who is engaged in Torah study cancels his study to hear the Megilla?

וַעֲבוֹדָה חֲמוּרָה מִתַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה? וְהָכְתִיב: ״וַיְהִי בִּהְיוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּירִיחוֹ וַיִּשָּׂא עֵינָיו וַיַּרְא וְהִנֵּה אִישׁ עוֹמֵד לְנֶגְדּוֹ [וְגוֹ׳] וַיִּשְׁתָּחוּ (לְאַפָּיו)״.

The Gemara asks: Is the Temple service more important than Torah study? Isn’t it written: “And it came to pass when Joshua was by Jericho that he lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, a man stood over against him with his sword drawn in his hand. And Joshua went over to him and said to him: Are you for us, or for our adversaries? And he said, No, but I am captain of the host of the Lord, I have come now. And Joshua fell on his face to the earth, and bowed down” (Joshua 5:13–14).

וְהֵיכִי עָבֵיד הָכִי? וְהָאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: אָסוּר לְאָדָם שֶׁיִּתֵּן שָׁלוֹם לַחֲבֵירוֹ בַּלַּיְלָה, חָיְישִׁינַן שֶׁמָּא שֵׁד הוּא! שָׁאנֵי הָתָם דְּאָמַר לֵיהּ: ״כִּי אֲנִי שַׂר צְבָא ה׳״.

The Gemara first seeks to clarify the incident described in the verse. How did Joshua do this, i.e., how could he bow to a figure he did not recognize? Didn’t Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi say: It is prohibited for a person to greet his fellow at night if he does not recognize him, as we are concerned that perhaps it is a demon? How did Joshua know that it was not a demon? The Gemara answers: There it was different, as the visitor said to him: But I am captain of the host of the Lord.

וְדִלְמָא מְשַׁקְּרִי? גְּמִירִי דְּלָא מַפְּקִי שֵׁם שָׁמַיִם לְבַטָּלָה.

The Gemara asks: Perhaps this was a demon and he lied? The Gemara answers: It is learned as a tradition that demons do not utter the name of Heaven for naught, and therefore since the visitor had mentioned the name of God, Joshua was certain that this was indeed an angel.

אָמַר לוֹ: אֶמֶשׁ בִּטַּלְתֶּם תָּמִיד שֶׁל בֵּין הָעַרְבַּיִם, וְעַכְשָׁיו בִּטַּלְתֶּם תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה. אָמַר לוֹ: עַל אֵיזֶה מֵהֶן בָּאתָ? אָמַר לוֹ: ״עַתָּה בָאתִי״, מִיָּד: ״וַיָּלֶן יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בַּלַּיְלָה הַהוּא בְּתוֹךְ הָעֵמֶק״, אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן:

As for the angel’s mission, the Gemara explains that the angel said to Joshua: Yesterday, i.e., during the afternoon, you neglected the afternoon daily offering due to the impending battle, and now, at night, you have neglected Torah study, and I have come to rebuke you. Joshua said to him: For which of these sins have you come? He said to him: I have come now, indicating that neglecting Torah study is more severe than neglecting to sacrifice the daily offering. Joshua immediately determined to rectify the matter, as the verses states: “And Joshua lodged that night” (Joshua 8:9) “in the midst of the valley [ha’emek]” (Joshua 8:13), and Rabbi Yoḥanan said:

מְלַמֵּד שֶׁלָּן בְּעוּמְקָהּ שֶׁל הֲלָכָה. וְאָמַר רַב שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר אוּנְיָא: גָּדוֹל תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה יוֹתֵר מֵהַקְרָבַת תְּמִידִין, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״עַתָּה בָאתִי״!

This teaches that he spent the night in the depths [be’umeka] of halakha, i.e., that he spent the night studying Torah with the Jewish people. And Rav Shmuel bar Unya said: Torah study is greater than sacrificing the daily offerings, as it is stated: “I have come now” (Joshua 5:14), indicating that the angel came to rebuke Joshua for neglecting Torah study and not for neglecting the daily offering. Consequently, how did the Sages of the house of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi determine that the Temple service is more important than Torah study?

לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָא דְּרַבִּים, וְהָא דְּיָחִיד.

The Gemara explains that it is not difficult. This statement, with regard to the story of Joshua, is referring to Torah study by the masses, which is greater than the Temple service. That statement of the Sages of the house of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi is referring to Torah study by an individual, which is less significant than the Temple service.

וּדְיָחִיד קַל? וְהָתְנַן: נָשִׁים בַּמּוֹעֵד מְעַנּוֹת אֲבָל לֹא מְטַפְּחוֹת, רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל אוֹמֵר: אִם הָיוּ סְמוּכוֹת לַמִּטָּה — מְטַפְּחוֹת. בְּרָאשֵׁי חֳדָשִׁים בַּחֲנוּכָּה וּבְפוּרִים, מְעַנּוֹת וּמְטַפְּחוֹת בָּזֶה וּבָזֶה, אֲבָל לֹא מְקוֹנְנוֹת.

The Gemara asks: Is the Torah study of an individual a light matter? Didn’t we learn in a mishna: On the intermediate days of a Festival, women may lament the demise of the deceased in unison, but they may not clap their hands in mourning? Rabbi Yishmael says: Those that are close to the bier may clap. On the New Moon, on Hanukkah, and on Purim, which are not mandated by Torah law, they may both lament and clap their hands in mourning. However, on both groups of days, they may not wail responsively, a form of wailing where one woman wails and the others repeat after her.

וְאָמַר רַבָּה בַּר הוּנָא: אֵין מוֹעֵד בִּפְנֵי תַּלְמִיד חָכָם — כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן חֲנוּכָּה וּפוּרִים.

And Rabba bar Huna said: All these regulations were said with regard to an ordinary person, but there are no restrictions on expressions of mourning on the intermediate days of a Festival in the presence of a deceased Torah scholar. If a Torah scholar dies on the intermediate days of a Festival, the women may lament, clap, and wail responsively as on any other day, and all the more so on Hanukkah and Purim. This indicates that even the Torah study of an individual is of great importance.

כְּבוֹד תּוֹרָה קָאָמְרַתְּ. כְּבוֹד תּוֹרָה דְּיָחִיד — חָמוּר, תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה דְּיָחִיד — קַל.

The Gemara rejects this argument: You speak of the honor that must be shown to the Torah, and indeed, the honor that must be shown to the Torah in the case of an individual Torah scholar is important; but the Torah study of an individual in itself is light and is less significant than the Temple service.

אָמַר רָבָא, פְּשִׁיטָא לִי: עֲבוֹדָה וּמִקְרָא מְגִילָּה — מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה עֲדִיף, מִדְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא. תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה וּמִקְרָא מְגִילָּה — מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה עֲדִיף, מִדְּסָמְכוּ שֶׁל בֵּית רַבִּי.

§ Rava said: It is obvious to me that if one must choose between Temple service and reading the Megilla, reading the Megilla takes precedence, based upon the exposition of Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina with regard to the phrase “every family” (Esther 9:28). Similarly, if one must choose between Torah study and reading the Megilla, reading the Megilla takes precedence, based upon the fact that the Sages of the house of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi relied on Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina’s exposition to rule that one interrupts Torah study to hear the reading of the Megilla.

תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה וּמֵת מִצְוָה — מֵת מִצְוָה עֲדִיף, מִדְּתַנְיָא: מְבַטְּלִין תַּלְמוּד תּוֹרָה לְהוֹצָאַת מֵת, וּלְהַכְנָסַת כַּלָּה. עֲבוֹדָה וּמֵת מִצְוָה — מֵת מִצְוָה עֲדִיף, מִ״וּלְאַחוֹתוֹ״.

Furthermore, it is obvious that if one must choose between Torah study and tending to a corpse with no one to bury it [met mitzva], the task of burying the met mitzva takes precedence. This is derived from that which is taught in a baraita: One cancels his Torah study to bring out a corpse for burial, and to join a wedding procession and bring in the bride. Similarly, if one must choose between the Temple service and tending to a met mitzva, tending to the met mitzva takes precedence, based upon the halakha derived from the term “or for his sister” (Numbers 6:7).

דְּתַנְיָא: ״וּלְאַחוֹתוֹ״ מַה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר? הֲרֵי שֶׁהָיָה הוֹלֵךְ לִשְׁחוֹט אֶת פִּסְחוֹ וְלָמוּל אֶת בְּנוֹ, וְשָׁמַע שֶׁמֵּת לוֹ מֵת, יָכוֹל יִטַּמָּא —

As it is taught in a baraita with regard to verses addressing the laws of a nazirite: “All the days that he consecrates himself to the Lord, he shall not come near to a dead body. For his father, or for his mother, for his brother, or for his sister, he shall not make himself ritually impure for them when they die” (Numbers 6:6–7). What is the meaning when the verse states “or for his sister”? The previous verse, which states that the nazirite may not come near a dead body, already prohibits him from becoming impure through contact with his sister. Therefore, the second verse is understood to be teaching a different halakha: One who was going to slaughter his Paschal lamb or to circumcise his son, and he heard that a relative of his died, one might have thought that he should return and become ritually impure with the impurity imparted by a corpse.

אָמַרְתָּ: ״לֹא יִטַּמָּא״. יָכוֹל כְּשֵׁם שֶׁאֵינוֹ מִיטַּמֵּא לַאֲחוֹתוֹ, כָּךְ אֵינוֹ מִיטַּמֵּא לְמֵת מִצְוָה — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״וּלְאַחוֹתוֹ״. לַאֲחוֹתוֹ הוּא דְּאֵינוֹ מִיטַּמֵּא, אֲבָל מִיטַּמֵּא לְמֵת מִצְוָה.

You said: He shall not become impure; the death of his relative will not override so significant a mitzva from the Torah. One might have thought: Just as he does not become impure for his sister, so he does not become impure for a corpse with no one to bury it [met mitzva]. The verse states: “Or for his sister”; he may not become impure for his sister, as someone else can attend to her burial, but he does become impure for a met mitzva.

בָּעֵי רָבָא: מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה וּמֵת מִצְוָה הֵי מִינַּיְיהוּ עֲדִיף? מִקְרָא מְגִילָּה עֲדִיף מִשּׁוּם פַּרְסוֹמֵי נִיסָּא, אוֹ דִּלְמָא מֵת מִצְוָה עֲדִיף מִשּׁוּם כְּבוֹד הַבְּרִיּוֹת? בָּתַר דְּבַעְיָא הֲדַר פַּשְׁטַהּ: מֵת מִצְוָה עֲדִיף, דְּאָמַר מָר: גָּדוֹל כְּבוֹד הַבְּרִיּוֹת שֶׁדּוֹחֶה אֶת לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה.

On the basis of these premises, Rava raised a dilemma: If one must choose between reading the Megilla and tending to a met mitzva, which of them takes precedence? Does reading the Megilla take precedence due to the value of publicizing the miracle, or perhaps burying the met mitzva takes precedence due to the value of preserving human dignity? After he raised the dilemma, Rava then resolved it on his own and ruled that attending to a met mitzva takes precedence, as the Master said: Great is human dignity, as it overrides a prohibition in the Torah. Consequently, it certainly overrides the duty to read the Megilla, despite the fact that reading the Megilla publicizes the miracle.

גּוּפָא, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: כְּרַךְ, וְכׇל הַסָּמוּךְ לוֹ, וְכׇל הַנִּרְאֶה עִמּוֹ — נִדּוֹן כִּכְרַךְ. תָּנָא: סָמוּךְ — אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵינוֹ נִרְאֶה, נִרְאֶה — אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵינוֹ סָמוּךְ.

§ The Gemara examines the matter itself cited in the course of the previous discussion. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: A walled city, and all settlements adjacent to it, and all settlements that can be seen with it, i.e., that can be seen from the walled city, are considered like the walled city, and the Megilla is read on the fifteenth. It was taught in the Tosefta: This is the halakha with regard to a settlement adjacent to a walled city, although it cannot be seen from it, and also a place that can be seen from the walled city, although it is not adjacent to it.

בִּשְׁלָמָא נִרְאֶה אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵינוֹ סָמוּךְ, מַשְׁכַּחַתְּ לַהּ כְּגוֹן דְּיָתְבָה בְּרֹאשׁ הָהָר. אֶלָּא סָמוּךְ אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵינוֹ נִרְאֶה הֵיכִי מַשְׁכַּחַתְּ לַהּ? אָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה: שֶׁיּוֹשֶׁבֶת בַּנַּחַל.

The Gemara examines the Tosefta: Granted that with regard to a place that can be seen from the walled city, although it is not adjacent to it, you find it where the place is located on the top of a mountain, and therefore it can be seen from the walled city, although it is at some distance from it. However, with regard to a settlement that is adjacent to a walled city although it cannot be seen from it, how can you find these circumstances? Rabbi Yirmeya said: You find it, for example, where the place is located in a valley, and therefore it is possible that it cannot be seen from the walled city, although it is very close to it.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: כְּרַךְ שֶׁיָּשַׁב וּלְבַסּוֹף הוּקַּף — נִדּוֹן כִּכְפָר. מַאי טַעְמָא? דִּכְתִיב: ״וְאִישׁ כִּי יִמְכּוֹר בֵּית מוֹשַׁב עִיר חוֹמָה״, שֶׁהוּקַּף וּלְבַסּוֹף יָשַׁב, וְלֹא שֶׁיָּשַׁב וּלְבַסּוֹף הוּקַּף.

And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: A walled city that was initially settled and only later surrounded by a wall is considered a village rather than a walled city. What is the reason? As it is written: “And if a man sells a residential house in a walled city” (Leviticus 25:29). The wording of the verse indicates that it is referring to a place that was first surrounded by a wall and only later settled, and not to a place that was first settled and only later surrounded by a wall.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: כְּרַךְ שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ עֲשָׂרָה בַּטְלָנִין — נִדּוֹן כִּכְפָר. מַאי קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן? תְּנֵינָא: אֵיזוֹ הִיא עִיר גְּדוֹלָה — כֹּל שֶׁיֵּשׁ בָּהּ עֲשָׂרָה בַּטְלָנִין. פָּחוֹת מִכָּאן, הֲרֵי זֶה כְּפָר? כְּרַךְ אִיצְטְרִיךְ לֵיהּ, אַף עַל גַּב דְּמִיקַּלְעִי לֵיהּ מֵעָלְמָא.

And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: A walled city that does not have ten idlers, i.e., individuals who do not work and are available to attend to communal needs, is treated as a village. The Gemara asks: What is he teaching us? We already learned in a mishna (5a): What is a large city? Any city in which there are ten idlers; however, if there are fewer than that, it is a village. The Gemara answers: Nevertheless, it was necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to teach this halakha with regard to a large city, to indicate that even if idlers happen to come there from elsewhere, since they are not local residents, it is still considered a village.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: כְּרַךְ שֶׁחָרַב וּלְבַסּוֹף יָשַׁב נִדּוֹן כִּכְרַךְ. מַאי חָרַב? אִילֵּימָא חָרְבוּ חוֹמוֹתָיו: יָשַׁב — אִין, לֹא יָשַׁב — לָא? וְהָא תַּנְיָא, רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר בַּר יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: ״אֲשֶׁר לוֹא חוֹמָה״, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ עַכְשָׁיו וְהָיָה לוֹ קוֹדֶם לָכֵן.

And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi also said: A walled city that was destroyed and then later settled is considered a city. The Gemara asks: What is meant by the term destroyed? If we say that the city’s walls were destroyed, and Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi comes to teach us that if it was settled, yes it is treated as a walled city, but if it was not settled, it is not treated that way, there is a difficulty. Isn’t it taught in a baraita that Rabbi Eliezer bar Yosei says: The verse states: “Which has [lo] a wall (Leviticus 25:30),” and the word lo is written with an alef, which means no, but in context the word lo is used as though it was written with a vav, meaning that it has a wall. This indicates that even though the city does not have a wall now, as the wall was destroyed, if it had a wall before, it retains its status as a walled city.

אֶלָּא מַאי ״חָרַב״ — שֶׁחָרַב מֵעֲשָׂרָה בַּטְלָנִין.

Rather, what is meant by the term destroyed? That it was destroyed in the sense that it no longer has ten idlers, and therefore it is treated like a village. However, once it has ten idlers again, it is treated like a city.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי:

And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said:

לוֹד וְאוֹנוֹ וְגֵיא הַחֲרָשִׁים — מוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן הֲווֹ.

The cities Lod, and Ono, and Gei HeḤarashim are cities that have been surrounded by walls since the days of Joshua, son of Nun.

וְהָנֵי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בְּנַנְהִי? וְהָא אֶלְפַּעַל בְּנַנְהִי, דִּכְתִיב: ״[וּ]בְנֵי אֶלְפַּעַל עֵבֶר וּמִשְׁעָם וָשָׁמֶר הוּא בָּנָה אֶת אוֹנוֹ וְאֶת לוֹד וּבְנוֹתֶיהָ״! וּלְטַעְמָיךְ, אָסָא בְּנַנְהִי, דִּכְתִיב: ״וַיִּבֶן (אָסָא אֶת עָרֵי הַבְּצוּרוֹת אֲשֶׁר לִיהוּדָה)״.

The Gemara asks: Did Joshua, son of Nun, really build these cities? Didn’t Elpaal build them at a later date, as it is written: “And the sons of Elpaal: Eber, and Misham, and Shemed, who built Ono and Lod, with its hamlets” (I Chronicles 8:12)? The Gemara counters: According to your reasoning, that this verse proves that these cities were built later, you can also say that Asa, king of Judah, built them, as it is written: “And he, Asa, built fortified cities in Judah” (see II Chronicles 14:5). Therefore, it is apparent that these cities were built more than once.

אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר: הָנֵי מוּקָּפוֹת חוֹמָה מִימוֹת יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בִּן נוּן הֲווֹ. חֲרוּב בִּימֵי פִּילֶגֶשׁ בְּגִבְעָה, וַאֲתָא אֶלְפַּעַל בְּנַנְהִי. הֲדוּר אִינְּפוּל, אֲתָא אָסָא שַׁפְּצִינְהוּ.

Rabbi Elazar said: These cities were surrounded by a wall since the days of Joshua, son of Nun, and they were destroyed in the days of the concubine in Gibea, as they stood in the tribal territory of Benjamin, and in that war all of the cities of Benjamin were destroyed (see Judges, chapters 19–21). Elpaal then came and built them again. They then fell in the wars between Judah and Israel, and Asa came and restored them.

דַּיְקָא נָמֵי, דִּכְתִיב: ״וַיֹּאמֶר לִיהוּדָה נִבְנֶה אֶת הֶעָרִים הָאֵלֶּה״, מִכְּלָל דְּעָרִים הֲווֹ מֵעִיקָּרָא. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

The Gemara comments: The language of the verse is also precise according to this explanation, as it is written with regard to Asa: “And he said to Judah: Let us build these cities” (II Chronicles 14:6), which proves by inference that they had already been cities at the outset, and that he did not build new cities. The Gemara concludes: Indeed, learn from this that it is so.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: נָשִׁים חַיָּיבוֹת בְּמִקְרָא מְגִילָּה, שֶׁאַף הֵן הָיוּ בְּאוֹתוֹ הַנֵּס. וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: פּוּרִים שֶׁחָל לִהְיוֹת בְּשַׁבָּת, שׁוֹאֲלִין וְדוֹרְשִׁין בְּעִנְיָנוֹ שֶׁל יוֹם.

§ And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi also said: Women are obligated in the reading of the Megilla, as they too were significant partners in that miracle. And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi also said: When Purim occurs on Shabbat, one asks questions and expounds upon the subject of the day.

מַאי אִרְיָא פּוּרִים? אֲפִילּוּ יוֹם טוֹב נָמֵי! דְּתַנְיָא: מֹשֶׁה תִּיקֵּן לָהֶם לְיִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁיְּהוּ שׁוֹאֲלִין וְדוֹרְשִׁין בְּעִנְיָנוֹ שֶׁל יוֹם: הִלְכוֹת פֶּסַח בַּפֶּסַח, הִלְכוֹת עֲצֶרֶת בָּעֲצֶרֶת, וְהִלְכוֹת חַג בֶּחָג!

The Gemara raises a question with regard to the last halakha: Why was it necessary to specify Purim? The same principle applies also to the Festivals, as it is taught in a baraita: Moses enacted for the Jewish people that they should ask questions about and expound upon the subject of the day: They should occupy themselves with the halakhot of Passover on Passover, with the halakhot of Shavuot on Shavuot, and with the halakhot of the festival of Sukkot on the festival of Sukkot.

פּוּרִים אִיצְטְרִיכָא לֵיהּ, מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: נִגְזוֹר מִשּׁוּם דְּרַבָּה, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara answers: It was necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to mention Purim, lest you say that when Purim falls on Shabbat we should decree that it is prohibited to expound upon the halakhot of the day due to the concern of Rabba, who said that the reason the Megilla is not read on a Purim that falls on Shabbat is due to a concern that one carry the Megilla in the public domain. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi therefore teaches us that expounding the halakhot of the day is not prohibited as a preventive measure lest one read the Megilla on Shabbat.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי: חַיָּיב אָדָם לִקְרוֹת אֶת הַמְּגִילָּה בַּלַּיְלָה וְלִשְׁנוֹתָהּ בַּיּוֹם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אֱלֹהַי אֶקְרָא יוֹמָם וְלֹא תַעֲנֶה וְלַיְלָה וְלֹא דוּמִיָּה לִי״.

And Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi further said with regard to Purim: A person is obligated to read the Megilla at night and then to repeat it [lishnota] during the day, as it is stated: “O my God, I call by day but You do not answer; and at night, and there is no surcease for me” (Psalms 22:3), which alludes to reading the Megilla both by day and by night.

סְבוּר מִינָּה לְמִקְרְיַיהּ בְּלֵילְיָא וּלְמִיתְנֵא מַתְנִיתִין דִּידַהּ בִּימָמָא. אֲמַר לְהוּ רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה: לְדִידִי מִיפָּרְשָׁא לִי מִינֵּיהּ דְּרַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא, כְּגוֹן דְּאָמְרִי אִינָשֵׁי: אֶעֱבוֹר פָּרַשְׁתָּא דָּא וְאֶתְנְיַיהּ.

Some of the students who heard this statement understood from it that one is obligated to read the Megilla at night and to study its relevant tractate of Mishna by day, as the term lishnota can be understood to mean studying Mishna. Rabbi Yirmeya said to them: It was explained to me personally by Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba himself that the term lishnota here has a different connotation, for example, as people say: I will conclude this section and repeat it, i.e., I will review my studies. Similarly, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi’s statement means that one must repeat the reading of the Megilla by day after reading it at night.

אִיתְּמַר נָמֵי, אָמַר רַבִּי חֶלְבּוֹ אָמַר עוּלָּא בִּירָאָה: חַיָּיב אָדָם לִקְרוֹת אֶת הַמְּגִילָּה בַּלַּיְלָה וְלִשְׁנוֹתָהּ בַּיּוֹם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״לְמַעַן יְזַמֶּרְךָ כָבוֹד וְלֹא יִדּוֹם ה׳ אֱלֹהַי לְעוֹלָם אוֹדֶךָּ״.

The Gemara notes that this ruling was also stated by another amora, as Rabbi Ḥelbo said that Ulla Bira’a said: A person is obligated to read the Megilla at night and then repeat it during the day, as it is stated: “So that my glory may sing praise to You and not be silent; O Lord, my God, I will give thanks to You forever” (Psalms 30:13). The dual formulation of singing praise and not being silent alludes to reading the Megilla both by night and by day.

אֶלָּא שֶׁהַכְּפָרִים מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה. אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִינָא: חֲכָמִים הֵקֵילּוּ עַל הַכְּפָרִים לִהְיוֹת מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּסַפְּקוּ מַיִם וּמָזוֹן לַאֲחֵיהֶם שֶׁבַּכְּרַכִּין.

§ We learned in the mishna that residents of unwalled towns read the Megilla on the fourteenth of Adar; however, residents of villages may advance their reading to the day of assembly, the Monday or Thursday preceding Purim. Rabbi Ḥanina said: The Sages were lenient with the villages and allowed them to advance their reading of the Megilla to the day of assembly, so that they could be free to provide water and food to their brethren in the cities on the day of Purim. If everyone would be busy reading the Megilla on the fourteenth, the residents of the cities would not have enough to eat.

לְמֵימְרָא דְּתַקַּנְתָּא דִכְרַכִּין הָוֵי? וְהָתְנַן: חָל לִהְיוֹת בַּשֵּׁנִי — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם. וְאִם אִיתָא, לַיקְדְּמוּ לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה! הָווּ לְהוּ עֲשָׂרָה, וַעֲשָׂרָה לָא תַּקִּינוּ רַבָּנַן.

The Gemara asks: Is that to say that this ordinance is for the benefit of the cities? Didn’t we learn in the mishna that if the fourteenth occurred on a Monday, the residents of villages and large towns read it on that very day? If it is so, that the ordinance allowing the villagers to sometimes advance their reading of the Megilla is for the benefit of the cities, let the villagers advance their reading to the previous day of assembly even when the fourteenth occurs on a Monday. The Gemara responds: That would mean that Megilla reading for them would take place on the tenth of Adar, and the Sages did not establish the tenth of Adar as a day that is fit to read the Megilla.

תָּא שְׁמַע: חָל לִהְיוֹת בַּחֲמִישִׁי — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם, וְאִם אִיתָא, לַיקְדְּמוּ לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה דְּאַחַד עָשָׂר הוּא! מִיּוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה לָא דָּחֵינַן.

The Gemara continues: Come and hear a proof from a different statement of the mishna: If the fourteenth occurs on a Thursday, the villages and large towns read it on that day, the fourteenth, and the walled cities read it on the next day, the fifteenth. If it is so, that the ordinance is for the benefit of the cities, let the villagers advance their reading of the Megilla to the previous day of assembly, i.e., the previous Monday, as it is the eleventh of Adar. The Gemara responds: We do not defer the reading of the Megilla from one day of assembly to another day of assembly.

תָּא שְׁמַע, אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֵימָתַי — בִּמְקוֹם שֶׁנִּכְנָסִים בַּשֵּׁנִי וּבַחֲמִישִׁי, אֲבָל מְקוֹם שֶׁאֵין נִכְנָסִים בַּשֵּׁנִי וּבַחֲמִישִׁי — אֵין קוֹרִין אוֹתָהּ אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּהּ. וְאִי סָלְקָא דַעְתָּךְ תַּקַּנְתָּא דִכְרַכִּין הִיא — מִשּׁוּם דְּאֵין נִכְנָסִים בַּשֵּׁנִי וּבַחֲמִישִׁי מַפְסְדִי לְהוּ לִכְרַכִּין?

The Gemara continues: Come and hear that which was taught in the following mishna (5a): Rabbi Yehuda said: When is the Megilla read from the eleventh of Adar and onward? In a place where the villagers generally enter town on Monday and Thursday. However, in a place where they do not generally enter town on Monday and Thursday, one may read the Megilla only in its designated time, the fourteenth of Adar. The Gemara infers: If it enters your mind to say that the ordinance is for the benefit of the cities, would it be reasonable to suggest that because the villagers do not enter town on Monday and Thursday the residents of the cities should lose out and not be provided with food and water?

לָא תֵּימָא כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּסַפְּקוּ מַיִם וּמָזוֹן, אֶלָּא אֵימָא: מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמְּסַפְּקִים מַיִם וּמָזוֹן לַאֲחֵיהֶם שֶׁבַּכְּרַכִּין.

The Gemara accepts this argument: Do not say that the Sages allowed the villages to advance their reading of the Megilla to the day of assembly so that they can be free to provide water and food to their brethren in the cities on the day of Purim. Rather, say that the Sages were lenient with them because the villages supply water and food to their brethren in the cities. This ordinance was established for the benefit of the villagers so that they should not have to make an extra trip to the cities to hear the reading of the Megilla. However, in a place where the villages do not go to the cities, advancing their reading of the Megilla to the day of assembly will not benefit them, and therefore they must read on the fourteenth.

כֵּיצַד? חָל לִהְיוֹת בַּשֵּׁנִי בַּשַּׁבָּת — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם וְכוּ׳. מַאי שְׁנָא רֵישָׁא דְּנָקֵט סִידּוּרָא דְיַרְחָא, וּמַאי שְׁנָא סֵיפָא דְּנָקֵט סִידּוּרָא דְיוֹמֵי?

§ We learned in the mishna: How so? If the fourteenth of Adar occurs on Monday, the villages and large towns read it on that day. The mishna continues to explain the days on which the Megilla is read. The Gemara asks: What is different about the first clause of the mishna, which employs the order of the dates of the month, i.e., the eleventh of Adar, and the latter clause, which employs the order of the days of the week, i.e., Monday?

אַיְּידֵי דְּמִיתְהַפְכִי לֵיהּ נָקֵט סִידּוּרָא דְיוֹמֵי.

The Gemara answers: Since the days of the week would be reversed if the latter clause was organized according to the dates of the month, as the mishna would first have to mention a case where the fourteenth occurs on a Sunday, then a case where it occurs on a Wednesday or Shabbat, and then a case where it occurs on a Friday or Tuesday, the mishna employed the order of the days of the week in order to avoid confusion.

חָל לִהְיוֹת בְּעֶרֶב שַׁבָּת וְכוּ׳. מַתְנִיתִין מַנִּי? אִי רַבִּי, אִי רַבִּי יוֹסֵי.

§ We learned in the mishna: If the fourteenth occurs on Shabbat eve, Friday, the villages advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Thursday, and the large towns and walled cities read it on Friday, the fourteenth of Adar. The Gemara asks: Whose opinion is expressed in the mishna? It can be either Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi or Rabbi Yosei.

מַאי רַבִּי? דְּתַנְיָא: חָל לִהְיוֹת בְּעֶרֶב שַׁבָּת — כְּפָרִים וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, וּמוּקָּפִין חוֹמָה קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם. רַבִּי אוֹמֵר, אוֹמֵר אֲנִי: לֹא יִדָּחוּ עֲיָירוֹת מִמְּקוֹמָן, אֶלָּא אֵלּוּ וָאֵלּוּ קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם.

The Gemara explains: What is the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi? As it is taught in a baraita: If the fourteenth occurs on Shabbat eve, villages and large towns advance their reading to the day of assembly, i.e., Thursday, and walled cities read it on the day of Purim, Friday. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi disagrees and says: I say that the readings in the large towns should not be deferred from their usual date, i.e., the fourteenth of Adar. Rather, both these, the large towns and those, the walled cities, read the Megilla on the day of Purim.

מַאי טַעְמָא דְּתַנָּא קַמָּא? דִּכְתִיב: ״בְּכׇל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה״. מָה כׇּל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה עֲיָירוֹת קוֹדְמוֹת לַמּוּקָּפִין, אַף כָּאן עֲיָירוֹת קוֹדְמוֹת לַמּוּקָּפִין.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason of the first tanna? The Gemara explains that it is as it is written: “To keep these two days, according to their writing and according to their time, in every year” (Esther 9:27), which indicates that Purim must be celebrated every year in similar fashion. Just as in every other year the large towns precede the walled cities by one day, so too here the large towns precede the walled cities by one day. Consequently, since the walled cities cannot read the Megilla on Shabbat and they are required to advance the reading to Friday, the large towns must also advance their reading a day to Thursday.

וְאֵימָא: ״בְּכׇל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה״, מָה כׇּל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה אֵין נִדְחִין עֲיָירוֹת מִמְּקוֹמָן — אַף כָּאן לֹא יִדָּחוּ עֲיָירוֹת מִמְּקוֹמָן! שָׁאנֵי הָכָא דְּלָא אֶפְשָׁר.

The Gemara raises an objection: Say that the words “in every year” indicate that just as in every other year the Megilla readings in the large towns are not deferred from their usual date and they read the Megilla on the fourteenth, so too here the Megilla readings in the large towns should not be deferred from their usual date and they too should read on the fourteenth. The Gemara answers: Here it is different, as it is not possible for the large towns to fulfill all of the conditions at the same time, i.e., to read on the fourteenth and to read a day before the walled cities.

וְרַבִּי, מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ? ״בְּכׇל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה״, מָה כׇּל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה אֵין עֲיָירוֹת נִדְחִין מִמְּקוֹמָן — אַף כָּאן לֹא יִדָּחוּ עֲיָירוֹת מִמְּקוֹמָן.

The Gemara asks: And Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, what is his reason? The Gemara explains that it is also based upon the words “in every year”; just as in every other year the readings in the large towns are not deferred from their usual date and they read on the fourteenth, so too here, the readings in the large towns are not deferred from their usual date, but rather they read on the fourteenth.

וְאֵימָא: ״בְּכׇל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה״, מָה כׇּל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה עֲיָירוֹת קוֹדְמוֹת לַמּוּקָּפִין — אַף כָּאן נָמֵי עֲיָירוֹת קוֹדְמוֹת לַמּוּקָּפִין! שָׁאנֵי הָכָא דְּלָא אֶפְשָׁר.

The Gemara raises an objection: Say that the words “in every year” indicate that just as every year the large towns precede the walled cities by one day, and read on the fourteenth, so too here the large towns precede the walled cities by one day, and read on the thirteenth. The Gemara answers: Here it is different, as it is not possible to fulfill all of the conditions at the same time, i.e., to read on the fourteenth and to read a day before the walled cities.

מַאי רַבִּי יוֹסֵי? דְּתַנְיָא: חָל לִהְיוֹת בְּעֶרֶב שַׁבָּת — מוּקָּפִין וּכְפָרִים מַקְדִּימִין לְיוֹם הַכְּנִיסָה, וַעֲיָירוֹת גְּדוֹלוֹת קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם. רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: אֵין מוּקָּפִין קוֹדְמִין לַעֲיָירוֹת, אֶלָּא אֵלּוּ וָאֵלּוּ קוֹרִין בּוֹ בַיּוֹם.

The Gemara asks: What is the opinion of Rabbi Yosei? As it is taught in a baraita: If the fourteenth occurs on Shabbat eve, the walled cities and villages advance their reading of the Megilla to the day of assembly, and the large towns read it on the day of Purim itself. Rabbi Yosei says: The walled cities never precede the large towns; rather, both these, the large towns, and those, the walled cities, read on that day, i.e., Friday, the fourteenth of Adar.

מַאי טַעְמָא דְּתַנָּא קַמָּא? דִּכְתִיב: ״בְּכׇל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה״, מָה כׇּל שָׁנָה וְשָׁנָה עֲיָירוֹת בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר, וּזְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה לֹא זְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה — אַף כָּאן עֲיָירוֹת בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר, וּזְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה לֹא זְמַנּוֹ שֶׁל זֶה.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason of the first tanna? As it is written: “In every year”; just as in every other year the large towns read the Megilla on the fourteenth, and the time for this type of settlement to read the Megilla is not the time for that type of settlement to read the Megilla, as the large towns and walled cities never read the Megilla on the same day, so too here, the large towns read the Megilla on the fourteenth, and the time for this type of settlement to read the Megilla is not the time for that type of settlement to read the Megilla. Therefore, the walled cities must advance their reading of the Megilla by two days to the day of assembly, Thursday.