Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Summary

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

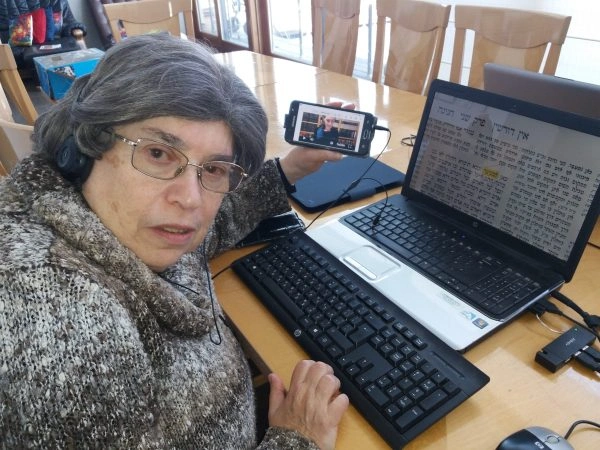

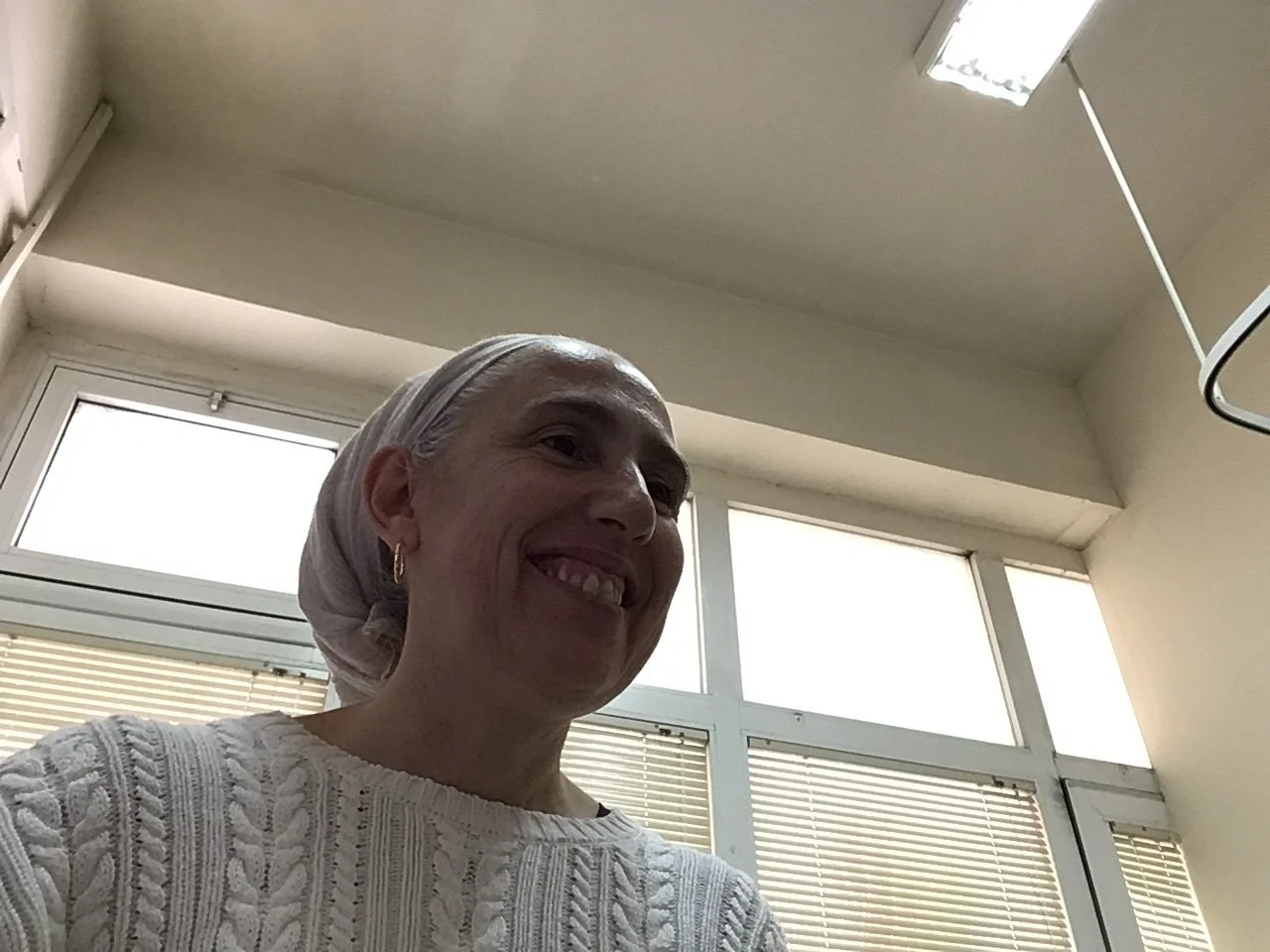

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Pesachim 5

דְּהָא אִיתַּקַּשׁ הַשְׁבָּתַת שְׂאוֹר לַאֲכִילַת חָמֵץ, וַאֲכִילַת חָמֵץ לַאֲכִילַת מַצָּה.

The time for the removal of leaven is juxtaposed to the time when the eating of leavened bread is prohibited. When the prohibition against eating leaven goes into effect, the obligation to remove leaven is in effect as well. And furthermore, the time of the prohibition against the eating of leavened bread is juxtaposed to the time for the eating of matza, as its prohibition takes effect from the time that the mitzva to eat matza takes effect.

הַשְׁבָּתַת שְׂאוֹר לַאֲכִילַת חָמֵץ, דִּכְתִיב: ״שִׁבְעַת יָמִים שְׂאֹר לֹא יִמָּצֵא בְּבָתֵּיכֶם כִּי כָּל אֹכֵל מַחְמֶצֶת וְנִכְרְתָה״.

The Gemara elaborates: The removal of leaven is juxtaposed to the eating of leavened bread, as they appear in the same verse, as it is written: “Seven days leaven shall not be found in your houses, as anyone who eats that which is leavened, that soul shall be cut off from the congregation of Israel” (Exodus 12:19).

וַאֲכִילַת חָמֵץ לַאֲכִילַת מַצָּה, דִּכְתִיב: ״כָּל מַחְמֶצֶת לֹא תֹאכֵלוּ בְּכֹל מוֹשְׁבֹתֵיכֶם תֹּאכְלוּ מַצּוֹת (וְגוֹ׳)״, וּכְתִיב בֵּיהּ בְּמַצָּה: ״בָּעֶרֶב תֹּאכְלוּ מַצּוֹת״.

And the prohibition against the eating of leavened bread is juxtaposed to the eating of matza, as both appear in the same verse, as it is written: “You shall not eat anything that is leavened; in all of your dwellings you shall eat matzot, etc.” (Exodus 12:20), and it is written with regard to matza: “On the first day, on the fourteenth day in the evening you shall eat matzot” (Exodus 12:18). Since the halakha that leaven is prohibited on the first night of Passover is derived from this source, there is no need for an additional derivation.

וְאֵימָא לְרַבּוֹת לֵיל אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר לְבִיעוּר? ״בַּיּוֹם״ כְּתִיב.

The Gemara asks: And say that the verse: “Yet on the first day you shall remove leaven from your houses” comes to include the night of the fourteenth in the obligation to remove leaven, which would mean that one must remove all leaven from his house on the night of the fourteenth. The Gemara rejects this suggestion: That is not possible, as “on the day” is written.

וְאֵימָא מִצַּפְרָא! ״אַךְ״ חִלֵּק.

The Gemara continues to ask: And say that leaven must be removed immediately from the morning of the fourteenth. The Gemara answers: That is also incorrect, as the verse says, “Yet on the first day”; and the word yet divides. The connotation of the word yet is one of restriction. In this context, it teaches that leaven is prohibited not for the entire day, but only for part of it. One is obligated to remove leaven only for the second half of the fourteenth of Nisan, not for the first half of the day.

דְּבֵי רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל תָּנָא: מָצִינוּ אַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר שֶׁנִּקְרָא רִאשׁוֹן, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״בָּרִאשׁוֹן בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר יוֹם לַחֹדֶשׁ״. רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק אָמַר: רִאשׁוֹן — דְּמֵעִיקָּרָא מַשְׁמַע, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״הָרִאשׁוֹן אָדָם תִּוָּלֵד״.

The school of Rabbi Yishmael taught: We found that the fourteenth day is called: First, as it is stated: “On harishon, on the fourteenth day of the month” (Exodus 12:18). Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said: It is evident from the verse itself that it is referring to the removal of leaven on the fourteenth, as rishon means previous. In this context, first means the day that precedes the others, i.e., the day before the Festival begins, as the verse stated: “Are you first [rishon] man born? Or were you brought forth before the hills?” (Job 15:7). Based on the parallelism between the two parts of the verse, the word rishon here means before; the one preceding all others.

אֶלָּא מֵעַתָּה, ״וּלְקַחְתֶּם לָכֶם בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן״, הָכִי נָמֵי רִאשׁוֹן דְּמֵעִיקָּרָא מַשְׁמַע?

The Gemara asks: But if that is so, consider a verse written with regard to Sukkot: “And you shall take for yourselves on the first [harishon] day the fruit of a beautiful tree, branches of palm trees, and boughs of thick trees, and willows of the brook” (Leviticus 23:40). So too, in this case, does harishon mean the day previous to the Festival? Clearly, one is not obligated to take the four species on the fourteenth of Tishrei, the eve of Sukkot.

שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דִּכְתִיב: ״וּשְׂמַחְתֶּם לִפְנֵי ה׳ אֱלֹהֵיכֶם שִׁבְעַת יָמִים״, מָה ״שְׁבִיעִי״ — שְׁבִיעִי לֶחָג, אַף ״רִאשׁוֹן״ — רִאשׁוֹן לֶחָג.

The Gemara rejects this contention. There it is different, as it is written immediately thereafter: “And you shall rejoice before the Lord your God seven days” (Leviticus 23:40). Just as the seventh of these seven days is the seventh day of the Festival, so too, the first of these days is the first day of the Festival itself, not the day before Sukkot. However, where it is not explicitly stated, rishon means the day before the Festival.

הָכָא נָמֵי כְּתִיב: ״אַךְ בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן תַּשְׁבִּיתוּ שִׁבְעַת יָמִים מַצּוֹת תֹּאכֵלוּ״! אִם כֵּן, נִכְתּוֹב קְרָא ״רִאשׁוֹן״, ״הָרִאשׁוֹן״ לְמָה לִי? שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ לִכְדַאֲמַרַן.

The Gemara raises a difficulty. Here too, it is written with regard to Passover: “Yet on the first [harishon] day you shall remove leaven from your houses”; “for seven days you shall eat matza” (Exodus 12:15). Just as seventh here is referring to the seventh day of the Festival, so too, rishon must refer to the first day of the Festival. The Gemara answers: If so, let the verse write rishon; why do I need the addition of the definite article, harishon? Learn from it, as we said: Harishon means the day before the Festival.

אִי הָכִי הָתָם נָמֵי, ״הָרִאשׁוֹן״ לְמָה לִי? וְתוּ, הָתָם דִּכְתִיב: ״בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן שַׁבָּתוֹן וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי שַׁבָּתוֹן״, אֵימַר ״רִאשׁוֹן״ דְּמֵעִיקָּרָא מַשְׁמַע? שָׁאנֵי הָתָם דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי שַׁבָּתוֹן״, מָה ״שְׁמִינִי״ — שְׁמִינִי דְּחַג, אַף ״רִאשׁוֹן״ — רִאשׁוֹן דְּחַג.

The Gemara raises an objection: If so, there too, with regard to Sukkot, why do I need the verse to say harishon? And furthermore, there it is written: “On the first [harishon] day a solemn rest and on the eighth day a solemn rest” (Leviticus 23:39). Here too, say that first means previous, the day preceding the Festival. The Gemara rejects this suggestion: It is different there, as the verse said: “And on the eighth day a solemn rest,” from which it can be inferred that just as the eighth means the eighth day of the Festival, so too, rishon is referring to the first day of the Festival.

״הָרִאשׁוֹן״ לְמָה לִי? לְמַעוֹטֵי חוּלּוֹ שֶׁל מוֹעֵד. חוּלּוֹ שֶׁל מוֹעֵד מֵ״רִאשׁוֹן״ וּ״שְׁמִינִי״ נָפְקָא!

The Gemara repeats its earlier question: Why do I need the verse to say harishon? The Gemara answers: The definite article comes to exclude the intermediate days of the Festival. It is not prohibited to perform labor on these days, as the full-fledged sanctity of the Festival does not apply to them. The Gemara says: The status of the intermediate days is derived from the words first and eighth. The fact that the verse mentions only the first and the eighth days as Festivals clearly indicates that the days between them are not Festivals.

אִיצְטְרִיךְ: סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא, הוֹאִיל דִּכְתַב רַחֲמָנָא: ״וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי״, וָיו מוֹסִיף עַל עִנְיָן רִאשׁוֹן, דַּאֲפִילּוּ בְּחוּלּוֹ שֶׁל מוֹעֵד, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara answers: Nevertheless, a special verse was necessary to exclude the intermediate Festival days, as otherwise it could enter your mind to say that since the Merciful One writes: “And on the eighth day,” the principle: The letter vav adds to the previous matter, applies. When a phrase begins with the conjunction vav, meaning and, it is a continuation of the previous matter rather than a new topic. Based on this principle, I might have said that one must treat even the intermediate days as full-fledged Festival days. Therefore, the definite article teaches us not that this is not so.

וְלָא לִכְתּוֹב רַחֲמָנָא לָא וָיו וְלָא הֵא?! וְתוּ, הָתָם דִּכְתִיב: ״בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן מִקְרָא קֹדֶשׁ יִהְיֶה לָכֶם״ — רִאשׁוֹן דְּמֵעִיקָּרָא מַשְׁמַע?!

The Gemara asks: And let the Merciful One write in the Torah neither the conjunction vav nor the definite article heh. Since they neutralize each other, as explained above, the same result could have been achieved by omitting both. And furthermore, there, in its description of Passover, it is written: “On the first [harishon] day you shall have a sacred convocation; you shall do no servile work” (Leviticus 23:7). Does first mean previous, the day preceding the Festival, in this case too? Labor is permitted on the eve of the Festival.

אֶלָּא, הָנֵי שְׁלֹשָׁה ״רִאשׁוֹן״ מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְכִדְתָנֵי דְּבֵי רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל. דְּתָנָא דְּבֵי רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל: בִּשְׂכַר שְׁלֹשָׁה ״רִאשׁוֹן״, זָכוּ לִשְׁלֹשָׁה ״רִאשׁוֹן״: לְהַכְרִית זַרְעוֹ שֶׁל עֵשָׂו, לְבִנְיַן בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, וְלִשְׁמוֹ שֶׁל מָשִׁיחַ.

Rather, the Gemara explains that those three times the word rishon is mentioned with regard to the Festivals are necessary for that which the school of Rabbi Yishmael taught. As the school of Rabbi Yishmael taught: In reward for the three times the word rishon is stated with regard to the Festivals observed by the Jewish people, they were entitled to three matters also referred to as rishon: To eradicate the descendants of Esau, to the construction of the Temple, and to the name of Messiah.

לְהַכְרִית זַרְעוֹ שֶׁל עֵשָׂו, דִּכְתִיב: ״וַיֵּצֵא הָרִאשׁוֹן אַדְמוֹנִי כֻּלּוֹ כְּאַדֶּרֶת שֵׂעָר״. וּלְבִנְיַן בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, דִּכְתִיב: ״כִּסֵּא כָבוֹד מָרוֹם מֵרִאשׁוֹן מְקוֹם מִקְדָּשֵׁנוּ״. וְלִשְׁמוֹ שֶׁל מָשִׁיחַ, דִּכְתִיב: ״רִאשׁוֹן לְצִיּוֹן הִנֵּה הִנָּם״.

The tanna provides the sources for his statement. To eradicate the descendants of Esau, as it is written: “And the first [harishon] came forth red, all over like a hairy mantle; and they called his name Esau” (Genesis 25:25). And to the construction of the Temple, as it is written: “The Throne of Glory, on High from the beginning [merishon], the place of our Temple” (Jeremiah 17:12). And the Jewish people were also entitled to the name of Messiah, as it is written: “A harbinger [rishon] to Zion I will give: Behold, behold them; and to Jerusalem a messenger of good tidings” (Isaiah 41:27). However, harishon stated with regard to Passover is referring to the day before the Festival.

רָבָא אָמַר, מֵהָכָא: ״לֹא תִשְׁחַט עַל חָמֵץ דַּם זִבְחִי״ — לֹא תִּשְׁחַט הַפֶּסַח וַעֲדַיִן חָמֵץ קַיָּים.

Rava said: The halakha that leaven is prohibited from midday on the fourteenth of Nisan is derived from here: “You shall not slaughter the blood of My offering over leavened bread; neither shall the offering of the feast of the Passover be left to the morning” (Exodus 34:25). This verse means that you shall not slaughter the Paschal lamb while your leavened bread is still intact. In other words, all leaven must be removed before the time the Paschal lamb may be slaughtered.

וְאֵימָא: כָּל חַד וְחַד כִּי שָׁחֵיט! זְמַן שְׁחִיטָה אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא.

The Gemara raises a difficulty: And say that the verse means that each and every person must ensure that he has no leaven in his possession when he slaughters his own Paschal lamb, and there is no fixed time for this prohibition. The Gemara answers: The Merciful One states the time of the slaughter of the Paschal lamb, which begins at the end of the sixth hour. In other words, this verse is referring to a particular point in time, rather than the individual act of slaughtering the Paschal lamb.

תַּנְיָא נָמֵי הָכִי: ״אַךְ בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן תַּשְׁבִּיתוּ שְּׂאֹר מִבָּתֵּיכֶם״ — מֵעֶרֶב יוֹם טוֹב. אוֹ אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא בְּיוֹם טוֹב עַצְמוֹ? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״לֹא תִשְׁחַט עַל חָמֵץ דַּם זִבְחִי״ — לֹא תִּשְׁחַט אֶת הַפֶּסַח וַעֲדַיִין חָמֵץ קַיָּים, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל.

The Gemara adds that some of the aforementioned opinions were also taught in a baraita: “Yet on the first day you shall remove leaven from your houses” (Exodus 12:15). This prohibition is in effect from the eve of the Festival. Or perhaps that is not the case, but it applies only to the Festival itself. The verse states: “You shall not slaughter the blood of My offering over leavened bread” (Exodus 34:25), meaning that you shall not slaughter the Paschal lamb while your leavened bread is still intact. This is the statement of Rabbi Yishmael.

רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ, הֲרֵי הוּא אוֹמֵר: ״אַךְ בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן תַּשְׁבִּיתוּ שְּׂאֹר מִבָּתֵּיכֶם״, וּכְתִיב: ״כָּל מְלָאכָה לֹא (תַעֲשׂוּ)״, וּמָצִינוּ לַהַבְעָרָה שֶׁהִיא אַב מְלָאכָה.

Rabbi Akiva says: There is no need for this proof, as it says: “Yet on the first day you shall remove leaven from your houses,” and it is written: “And on the first day there shall be to you a sacred convocation, and on the seventh day a sacred convocation; you shall perform no manner of work on them” (Exodus 12:16). And we found that kindling a fire is a primary category of prohibited labor. Since the fire in which the leaven is burned is not for the preparation of food, kindling it is not performed for the purpose of the Festival. Therefore, it is prohibited to burn the leaven on the Festival itself. Consequently, one must burn the leaven on the day before the Festival.

רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ, הֲרֵי הוּא אוֹמֵר: ״אַךְ בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן תַּשְׁבִּיתוּ שְּׂאֹר מִבָּתֵּיכֶם״ — מֵעֶרֶב יוֹם טוֹב. אוֹ אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא בְּיוֹם טוֹב — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״אַךְ״, חִלֵּק. וְאִי בְּיוֹם טוֹב עַצְמוֹ, מִי שְׁרֵי? הָא אִיתַּקַּשׁ הַשְׁבָּתַת שְׂאוֹר לַאֲכִילַת חָמֵץ, וַאֲכִילַת חָמֵץ לַאֲכִילַת מַצָּה! אָמַר רָבָא:

Rabbi Yosei says: There is no need for that proof either, as it says: “Yet on the first day you shall remove leaven from your houses.” This prohibition applies from the eve of the Festival. Or perhaps that is not the case, but it applies only to the Festival itself. The verse states: Yet, which comes to divide the day into two parts; the first half, when leaven is permitted, and the second half, when it is prohibited. And if this verse is referring to the first day of the Festival itself, is leaven permitted on the actual Festival? As explained above, the removal of leaven is juxtaposed to the eating of leavened bread, and the eating of leavened bread is juxtaposed to the eating of matza. Rava said:

שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ מִדְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא תְּלָת. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: אֵין בִּיעוּר חָמֵץ אֶלָּא שְׂרֵיפָה, וּשְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: הַבְעָרָה לְחַלֵּק יָצָאת, וּשְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: לָא אָמְרִינַן הוֹאִיל וְהוּתְּרָה הַבְעָרָה לְצוֹרֶךְ — הוּתְּרָה נָמֵי שֶׁלֹּא לְצוֹרֶךְ.

Learn from the statement of Rabbi Akiva three halakhot. Learn from it that the removal of leavened bread can be performed only by means of burning. Rabbi Akiva bases his opinion on the fact that it is prohibited to kindle a fire on the Festival.

And second, learn from it that the prohibition against kindling a fire on Shabbat was specifically singled out in the Torah to divide the various primary categories of labor and to establish liability for performance of each of them. The dissenting opinion is that kindling is singled out to teach that there is no capital punishment for performing that primary category of labor.

And third, learn from it that we do not say: Since it is permitted to kindle a fire for the purpose of preparing food, it is also permitted to light a fire not for the purpose of preparing food, e.g., to burn leaven.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״שִׁבְעַת יָמִים שְׂאֹר לֹא יִמָּצֵא בְּבָתֵּיכֶם״. מַה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר? וַהֲלֹא כְּבָר נֶאֱמַר: ״לֹא יֵרָאֶה לְךָ שְׂאֹר [וְלֹא יֵרָאֶה לְךָ חָמֵץ] בְּכׇל גְּבֻלֶךָ״!

The Sages taught in a baraita: “Seven days leaven shall not be found in your houses” (Exodus 12:19). To what purpose does the verse state this prohibition? Wasn’t it already stated: “And no leaven shall be seen with you, neither shall there be leavened bread seen with you, in all your borders” (Exodus 13:7)?

לְפִי שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״לֹא יֵרָאֶה לְךָ שְׂאֹר״ — שֶׁלְּךָ אִי אַתָּה רוֹאֶה, אֲבָל אַתָּה רוֹאֶה שֶׁל אֲחֵרִים וְשֶׁל גָּבוֹהַּ. יָכוֹל יַטְמִין וִיקַבֵּל פִּקְדוֹנוֹת מִן הַגּוֹי — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״לֹא יִמָּצֵא״.

The baraita answers: Because it is stated: “And no leaven shall be seen with you,” which teaches that your own leaven you may not see, but you may see leaven that belongs to others, i.e., gentiles, and leaven consecrated to God. In light of this halakha, I might have thought that one may conceal leaven in one’s home or accept deposits of leaven from a gentile. Therefore, the verse states: “Shall not be found,” meaning that one may not retain any type of leaven in one’s house at all.

אֵין לִי אֶלָּא בְּגוֹי שֶׁלֹּא כִּיבַּשְׁתּוֹ, וְאֵין שָׁרוּי עִמְּךָ בֶּחָצֵר. גּוֹי שֶׁכִּיבַּשְׁתּוֹ, וְשָׁרוּי עִמְּךָ בֶּחָצֵר מִנַּיִן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״לֹא יִמָּצֵא בְּבָתֵּיכֶם״.

The tanna continues: Had only this verse been stated, I would have derived nothing other than this halakha with regard to a gentile whom you did not overcome and who does not dwell with you in the courtyard. With regard to a gentile whom you overcame and who dwells with you in the courtyard, from where do we know that he is also included in this prohibition? The verse states: “It shall not be found in your houses” at all, i.e., anywhere in one’s possession.

אֵין לִי אֶלָּא שֶׁבְּבָתֵּיכֶם. בְּבוֹרוֹת בְּשִׁיחִין וּבִמְעָרוֹת מִנַּיִן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״בְּכׇל גְּבֻלֶךָ״.

The baraita further states that from the verse: “It shall not be found in your houses,” I have derived nothing other than the fact that this prohibition applies to leaven that is actually in your houses. From where is it derived that this halakha applies even to leaven in pits, ditches, and caves? The verse states: In all your borders, i.e., anywhere that belongs to you.

וַעֲדַיִין אֲנִי אוֹמֵר: בַּבָּתִּים עוֹבֵר מִשּׁוּם בַּל יֵרָאֶה וּבַל יִמָּצֵא וּבַל יַטְמִין וּבַל יְקַבֵּל פִּקְדוֹנוֹת מִן הַגּוֹי. בַּגְּבוּלִין — שֶׁלְּךָ אִי אַתָּה רוֹאֶה, אֲבָל אַתָּה רוֹאֶה שֶׁל אֲחֵרִים וְשֶׁל גָּבוֹהַּ. מִנַּיִין לִיתֵּן אֶת הָאָמוּר שֶׁל זֶה בָּזֶה וְשֶׁל זֶה בָּזֶה?

And still I can say: If there is leaven in your houses, one violates the prohibition that leaven shall not be seen and the prohibition that it shall not be found, as well as the prohibitions of you shall not conceal and you shall not receive deposits from a gentile. Meanwhile, in your borders, outside your home, your own leaven you may not see, but you may see leaven that belongs to others, i.e., gentiles, and leaven consecrated to God. From where is it derived that it is proper to apply the prohibition that was said about this place to that place, and the prohibition that was said about that place to this place?

תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״שְׂאוֹר״ ״שְׂאוֹר״ לִגְזֵירָה שָׁוָה. נֶאֱמַר שְׂאוֹר בַּבָּתִּים: ״שְׂאֹר לֹא יִמָּצֵא בְּבָתֵּיכֶם״, וְנֶאֱמַר שְׂאֹר בַּגְּבוּלִין: ״לֹא יֵרָאֶה לְךָ שְׂאֹר״. מָה שְׂאוֹר הָאָמוּר בַּבָּתִּים — עוֹבֵר מִשּׁוּם בַּל יֵרָאֶה וּבַל יִמָּצֵא וּבַל יַטְמִין וּבַל יְקַבֵּל פִּקְדוֹנוֹת מִן הַגּוֹיִם, אַף שְׂאוֹר הָאָמוּר בַּגְּבוּלִין — עוֹבֵר מִשּׁוּם בַּל יֵרָאֶה וּבַל יִמָּצֵא וּבַל יַטְמִין וּבַל יְקַבֵּל פִּקְדוֹנוֹת מִן הַגּוֹיִם.

The tanna answers that the verse states the term leaven with regard to houses and the term leaven with regard to borders as a verbal analogy. It states leaven with regard to houses: “Seven days leaven shall not be found in your houses,” and it states leaven with regard to borders: “Neither shall there be leaven seen with you.” Just as for the leaven stated with regard to houses one transgresses the prohibition that leaven shall not be seen and the prohibition that it shall not be found, and the prohibitions of one shall not conceal and one shall not receive deposits from a gentile, so too, for the leaven stated with regard to borders, one transgresses the prohibition that leaven shall not be seen and the prohibition that it shall not be found, and the prohibitions of one shall not conceal and one shall not receive deposits from a gentile.

וּמָה שְׂאוֹר הָאָמוּר בַּגְּבוּלִין — שֶׁלְּךָ אִי אַתָּה רוֹאֶה, אֲבָל אַתָּה רוֹאֶה שֶׁל אֲחֵרִים וְשֶׁל גָּבוֹהַּ, אַף שְׂאוֹר הָאָמוּר בַּבָּתִּים — שֶׁלְּךָ אִי אַתָּה רוֹאֶה, אֲבָל אַתָּה רוֹאֶה שֶׁל אֲחֵרִים וְשֶׁל גָּבוֹהַּ.

The converse is also true: Just as concerning the leaven stated with regard to borders, your own leaven you may not see, but you may see leaven that belongs to others, i.e., gentiles, and leaven consecrated to God, so too, concerning the leaven stated with regard to houses: Your own leaven you may not see, but you may see leaven that belongs to others and leaven consecrated to God.

אָמַר מָר: אֵין לִי אֶלָּא בְּגוֹי שֶׁלֹּא כִּיבַּשְׁתּוֹ, וְאֵין שָׁרוּי עִמְּךָ בֶּחָצֵר. גּוֹי שֶׁכִּיבַּשְׁתּוֹ, וְשָׁרוּי עִמְּךָ בֶּחָצֵר מִנַּיִן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״לֹא יִמָּצֵא״.

The Gemara addresses several difficult aspects of this baraita. The Master said: I would have derived nothing other than this halakha with regard to a gentile whom you did not overcome and who does not dwell with you in the courtyard. With regard to a gentile whom you overcame and who dwells with you in the courtyard, from where is it derived that he is also included in this prohibition? The verse states: “It shall not be found in your houses.”

כְּלַפֵּי לְיָיא! אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: אֵיפוֹךְ.

The Gemara questions the logic of this proof. On the contrary; the prohibition regarding the leaven of a gentile who is subservient to and lives with a Jew is more obvious than the prohibition regarding the leaven of a gentile who is neither. The tanna should have started with the leaven belonging to a gentile who is subservient to a Jew. Abaye said: Reverse the order of the statement: I might have thought that only leaven owned by a gentile whom you overcame and who dwells with you in the courtyard is prohibited; but leaven owned by a gentile whom you did not overcome and who does not dwell with you in the courtyard is permitted.

רָבָא אָמַר: לְעוֹלָם לָא תֵּיפוֹךְ, וְאַרֵישָׁא קָאֵי: שֶׁלְּךָ אִי אַתָּה רוֹאֶה, אֲבָל אַתָּה רוֹאֶה שֶׁל אֲחֵרִים וְשֶׁל גָּבוֹהַּ. אֵין לִי אֶלָּא בְּגוֹי שֶׁלֹּא כִּיבַּשְׁתּוֹ, וְאֵין שָׁרוּי עִמְּךָ בֶּחָצֵר. גּוֹי שֶׁכִּיבַּשְׁתּוֹ, וְשָׁרוּי עִמְּךָ בֶּחָצֵר, מִנַּיִן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״לֹא יִמָּצֵא״.

Rava said: Actually, do not reverse the order, as this statement is not in fact a continuation of the previous one and instead it applies to the first clause of the baraita, which deals with the time when leaven is permitted. The entire statement should read as follows: Your own leaven you may not see, but you may see leaven that belongs to others, i.e., gentiles, and leaven consecrated to God, as one is not commanded to remove leaven that belongs to a gentile. I have derived nothing other than this halakha with regard to a gentile whom you did not overcome and who does not dwell with you in the courtyard, as the leaven belonging to that gentile is in no way tied to the Jew. With regard to a gentile whom you overcame and who dwells with you in the courtyard, from where is it derived that he is also included in this leniency? The verse states: “It shall not be found.”

וְהַאי תַּנָּא מְיהַדַּר אַהֶיתֵּירָא, וְנָסֵיב לֵהּ קְרָא לְאִיסּוּרָא?! מִשּׁוּם שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ״לְךָ״ ״לְךָ״ תְּרֵי זִימְנֵי.

The Gemara raises a difficulty: This tanna seeks permission for seeing the leaven of a gentile, and yet he cites a verse to establish a prohibition. The Gemara answers that the tanna did not cite proof from the phrase: It shall not be found. Due to the fact that it is stated: “No leaven shall be seen with you in all your borders” (Exodus 13:7) and “No leaven shall be seen with you in all your borders” (Deuteronomy 16:4) twice, one of them is superfluous and may be appended to: It shall not be found, creating the prohibition: It shall not be found with you. Only leaven belonging to a Jew is prohibited.

אָמַר מָר: יָכוֹל יַטְמִין וִיקַבֵּל פִּקְדוֹנוֹת מִן הַגּוֹיִם, תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״לֹא יִמָּצֵא״. הָא אָמְרַתְּ רֵישָׁא: שֶׁלְּךָ אִי אַתָּה רוֹאֶה, אֲבָל אַתָּה רוֹאֶה שֶׁל אֲחֵרִים וְשֶׁל גָּבוֹהַּ!

The Gemara continues its analysis of the baraita. The Master said: I might have thought that one may conceal leaven in one’s home or accept deposits of leaven from the gentiles. Therefore, the verse states: It shall not be found. The Gemara asks: But didn’t you say in the first clause of the baraita: Your own leaven you may not see, but you may see leaven that belongs to others and leaven consecrated to God, indicating that it is permitted to have leaven in one’s house if it belongs to a gentile?

לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָא — דְּקַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ אַחְרָיוּת, הָא — דְּלָא קַבֵּיל עֲלֵיהּ אַחְרָיוּת.

The Gemara answers: This is not difficult; in this case it is prohibited, as he accepted upon himself responsibility to pay for the leaven if it is destroyed. Therefore, it is considered as though the leaven belonged to him. In that case it is permitted, as he did not accept upon himself responsibility, and therefore the leaven remains the full-fledged property of the gentile.

כִּי הָא דְּאָמַר לְהוּ רָבָא לִבְנֵי מָחוֹזָא: בַּעִירוּ חֲמִירָא דִבְנֵי חֵילָא מִבָּתַּיְיכוּ. כֵּיוָן דְּאִילּוּ מִיגְּנֵב וְאִילּוּ מִיתְּבִיד בִּרְשׁוּתַיְיכוּ קָאֵי וּבָעִיתוּ לְשַׁלּוֹמֵי — כְּדִילְכוֹן דָּמֵי, וְאָסוּר.

That ruling is like that which Rava said to the residents of Meḥoza: Remove the leavened bread that belongs to the members of the gentile army from your houses. Gentile soldiers would bring flour with them and force the people in the city to prepare bread on their behalf. Rava explained the rationale for his ruling: Since if the flour were stolen or if it were lost, it stands in your possession and you would be required to pay for it, its legal status is as if it were yours, and it is prohibited to keep it during Passover.

הָנִיחָא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר דָּבָר הַגּוֹרֵם לְמָמוֹן — כְּמָמוֹן דָּמֵי. אֶלָּא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר לָאו כְּמָמוֹן דָּמֵי, מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר?

The Gemara raises a difficulty: This explanation works out well according to the one who said: The legal status of an object that effects monetary loss is like that of money. If an item is inherently or currently worthless, but if it is lost or stolen one would be obligated to pay to replace it, its legal status is like that of money. Therefore, the Jews’ responsibility for the leaven renders its legal status as if it belonged to them. However, according to the one who said: The legal status of an object that effects monetary loss is not like that of money, what can be said?

שָׁאנֵי הָכָא, דְּאָמַר ״לֹא יִמָּצֵא״.

The Gemara answers: It is different here, as the verse said: “It shall not be found,” indicating that leaven may not be found in any place, even if there is only a token connection between the leaven and the Jew in whose property it is situated, and even if he is not required to pay for it if it is lost or stolen.

אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: הָנִיחָא לְמַאן דְּאָמַר דָּבָר הַגּוֹרֵם לְמָמוֹן — לָאו כְּמָמוֹן דָּמֵי,

Some state a contrary version of the above discussion. This explanation works out well according to the one who said: The legal status of an object that effects monetary loss is not like that of money.