Raba distinguishes between two cases of hearing half a shofar blast – in one he allows it (one who hears half a blast in a pit and half out of the pit) but not in the other (half before dawn and half after dawn). Why? In the case where it is permitted, the Gemara questions this based on other sources that seem to indicate that one cannot hear half a shofar blast. Raba statement is reinterpreted since the original understanding was rejected. Can one fulfill the mitzva of shofar if the shofar was taken from an animal sanctified for a sacrifice? On what does it depend? Different answers are brought. Rava concludes that all is permitted as when one fulfills a mitzva it is not considered that one benefitted. Therefore, one can hear a shofar from a person or a shofar to whom he vowed not to derive benefit from. Do mitzvot require intent? If not, then if one forced a person to eat matza, one fulfilled the mitzva and likewise if one blew a shofar for the music, one would fulfill the mitzva. Are these cases exactly the same? Rava said that mitzvot do not require intent. Several sources are brought to question this statement of Rava, one of them being the case in our Mishna of passing a shul when the shofar is being blown.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

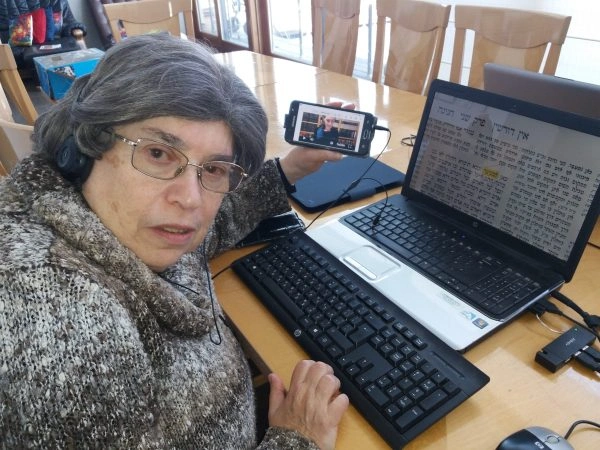

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Rosh Hashanah 28

שָׁמַע מִקְצָת תְּקִיעָה בַּבּוֹר וּמִקְצָת תְּקִיעָה עַל שְׂפַת הַבּוֹר — יָצָא. מִקְצָת תְּקִיעָה קוֹדֶם שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר וּמִקְצָת תְּקִיעָה לְאַחַר שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר — לֹא יָצָא.

If one heard part of the blast in the pit and part of the blast at the edge of the pit, he has fulfilled his obligation. But if he heard part of the blast before dawn, when it is not yet time to sound the shofar, and part of the blast after dawn, he has not fulfilled his obligation.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: מַאי שְׁנָא הָתָם — דְּבָעֵינָא כּוּלַּהּ תְּקִיעָה בְּחִיּוּבָא, וְלֵיכָּא. הָכָא נָמֵי — בָּעֵינָא כּוּלַּהּ תְּקִיעָה בְּחִיּוּבָא, וְלֵיכָּא!

Abaye said to him: What is different there, in the case of one who heard part of the blast before dawn and part of it after dawn? If you say that there the entire blast needs to be heard in a time of obligation, and when he hears part of the blast before dawn and part after dawn it is not all within the same time of obligation, here too, in the case of the pit, the entire blast needs to be in a place where one can fulfill his obligation, and when he hears part of the blast in a pit and part at the edge, it is not all within a place where he can fulfill his obligation.

הָכִי הַשְׁתָּא?! הָתָם — לַיְלָה לָאו זְמַן חִיּוּבָא הוּא כְּלָל, הָכָא — בּוֹר מְקוֹם חִיּוּבָא הוּא לְאוֹתָן הָעוֹמְדִין בַּבּוֹר.

The Gemara rejects this argument: How can these cases be compared? There, night is not a time of obligation at all, and sounding the shofar then has no meaning whatsoever, but here, a pit is a place of obligation for those standing in the pit. That is to say, the part of the blast that was heard in the pit is not inherently invalid, but merely disqualified due to an external factor, so that it is possible to connect it with the part of the blast that was heard at the edge of the pit.

לְמֵימְרָא דְּסָבַר רַבָּה: שָׁמַע סוֹף תְּקִיעָה בְּלֹא תְּחִילַּת תְּקִיעָה — יָצָא, וּמִמֵּילָא: תְּחִילַּת תְּקִיעָה בְּלֹא סוֹף תְּקִיעָה — יָצָא.

The Gemara asks: Is this to say that Rabba maintains that if one heard the end of a blast without hearing the beginning of the blast, he has fulfilled his obligation? Because in the case where one heard the beginning of the blast in a pit, he is considered to have heard only the end of the shofar blast, which he heard at the edge of the pit. And it therefore follows that if one heard the beginning of a blast without hearing the end of the blast, he has also fulfilled his obligation.

תָּא שְׁמַע: תָּקַע בָּרִאשׁוֹנָה, וּמָשַׁךְ בַּשְּׁנִיָּה כִּשְׁתַּיִם — אֵין בְּיָדוֹ אֶלָּא אַחַת. וְאַמַּאי? תִּסְלַק לֵהּ בְּתַרְתֵּי! פַּסּוֹקֵי תְּקִיעָתָא מֵהֲדָדֵי לָא פָּסְקִינַן.

Come and hear a proof that this is not so, for we learned in the mishna: If one blew the initial tekia of the first set of tekia-terua-tekia, and then drew out the second tekia so that it spans the length of two tekiot, it counts as only one tekia, and is not considered two tekiot, i.e., the concluding tekia of the first set, and the initial tekia of the second set. But why is this so? If we consider part of a blast as a complete one, let it count as two tekiot. The Gemara explains: If one hears only the beginning or the end of a shofar blast, he has indeed fulfilled his obligation, but nevertheless, we do not divide a shofar blast into two.

תָּא שְׁמַע: הַתּוֹקֵעַ לְתוֹךְ הַבּוֹר אוֹ לְתוֹךְ הַדּוּת אוֹ לְתוֹךְ הַפִּיטָס, אִם קוֹל שׁוֹפָר שָׁמַע — יָצָא, וְאִם קוֹל הֲבָרָה שָׁמַע — לֹא יָצָא. וְאַמַּאי? לִיפּוֹק בִּתְחִילַּת תְּקִיעָה מִקַּמֵּי דְּלִיעַרְבַּב קָלָא!

The Gemara raises another difficulty: Come and hear that which was taught in a mishna: If one sounds a shofar into a pit, or into a cistern, or into a large jug, if he clearly heard the sound of the shofar, he has fulfilled his obligation; but if he heard the sound of an echo, he has not fulfilled his obligation. But why is this so? If indeed half a blast is considered a blast, let him fulfill his obligation with the beginning of the blast, before the sound of the shofar is confused with the echo, since he heard the beginning of the blast clearly.

כִּי קָאָמַר רַבָּה — בְּתוֹקֵעַ וְעוֹלֶה לְנַפְשֵׁיהּ.

The Gemara answers: Indeed, half a blast is not considered a blast, and Rabba’s statement must be understood differently. When Rabba spoke, he was speaking not about other people hearing the blast, but about one who was sounding the shofar for himself in a pit and emerged from the pit as he was blowing. He has fulfilled his obligation, because he was located in the same place as the sound of the shofar at all times, and so he heard the entire blast clearly.

אִי הָכִי, מַאי לְמֵימְרָא? מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: זִמְנִין דְּמַפֵּיק רֵישֵׁיהּ וְאַכַּתִּי שׁוֹפָר בְּבוֹר, וְקָא מִיעַרְבַּב קָלָא — קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara asks: If so, what is the purpose of Rabba’s statement? The halakha in this case should be obvious, as there is no reason that the blast should be disqualified. The Gemara answers: Lest you say that his head might sometimes emerge from the pit while the shofar itself is still in the pit, and the sound may become confused with its echo, and so he would not fulfill his obligation. Therefore, Rabba teaches us that we are not concerned about this, and the obligation is considered to have been fulfilled.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: בְּשׁוֹפָר שֶׁל עוֹלָה — לֹא יִתְקַע, וְאִם תָּקַע — יָצָא. בְּשׁוֹפָר שֶׁל שְׁלָמִים — לֹא יִתְקַע, וְאִם תָּקַע — לֹא יָצָא.

§ Rav Yehuda said: One should not blow with the shofar of an animal consecrated as a burnt-offering, but if he nevertheless transgressed and blew, he has fulfilled his obligation. One should also not blow with the shofar of an animal consecrated as a peace-offering, and if he nevertheless transgressed and blew, he has not fulfilled his obligation.

מַאי טַעְמָא? עוֹלָה בַּת מְעִילָה הִיא, כֵּיוָן דְּמָעַל בַּהּ — נָפְקָא לַהּ לְחוּלִּין. שְׁלָמִים דְּלָאו בְּנֵי מְעִילָה נִינְהוּ — אִיסּוּרָא הוּא דְּרָכֵיב בְּהוּ, וְלָא נָפְקִי לְחוּלִּין.

The Gemara explains: What is the reason for this distinction? A burnt-offering is subject to misuse of consecrated objects before being offered, and once one misuses it for mundane purposes, it becomes non-sacred, so that the one who blows with its shofar fulfills his obligation. In contrast, peace-offerings are not subject to misuse of consecrated objects before being offered, since in the case of sacrifices of lesser sanctity, misuse is restricted to the fats and other portions that are offered on the altar, and even this applies only after the sprinkling of the blood. Since one is not considered to be misusing peace-offerings when utilizing them for mundane purposes, the prohibition remains intact and they do not become non-sacred. Therefore, one who blows the shofar of an animal consecrated as a peace-offering does not fulfill his obligation.

מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רָבָא: אֵימַת מָעַל — לְבָתַר דְּתָקַע, כִּי קָא תָּקַע — בְּאִיסּוּרָא תָּקַע.

Rava strongly objects to this argument: When does he commit misuse? After he has sounded it, for only then has he misused the consecrated animal. If so, when he sounds it, he is sounding with something that is still prohibited, even in the case of the animal that was consecrated as a burnt-offering, and so he should not be able to fulfill his obligation with it.

אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבָא: אֶחָד זֶה וְאֶחָד זֶה — לֹא יָצָא. הֲדַר אָמַר: אֶחָד זֶה וְאֶחָד זֶה — יָצָא. מִצְוֹת לָאו לֵיהָנוֹת נִיתְּנוּ.

Rather, Rava said: Both this one, the shofar of a burnt-offering, and the other one, the shofar of a peace-offering, are governed by the same halakha: If he sounded them, he has not fulfilled his obligation. Later, Rava retracted his statement and then said the opposite: Both this one, the shofar of a burnt-offering, and the other one, the shofar of a peace-offering, are governed by the same halakha: If he sounded them, he has fulfilled his obligation. The reason for this is that mitzvot were not given for benefit. That is to say, the fulfillment of a mitzva is not in itself considered a benefit, and in the absence of benefit, one is not liable for misuse.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: בְּשׁוֹפָר שֶׁל עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה — לֹא יִתְקַע, וְאִם תָּקַע — יָצָא. בְּשׁוֹפָר שֶׁל עִיר הַנִּדַּחַת — לֹא יִתְקַע, וְאִם תָּקַע — לֹא יָצָא. מַאי טַעְמָא: עִיר הַנִּדַּחַת כַּתּוֹתֵי מְיכַתַּת שִׁיעוּרֵיהּ.

Rav Yehuda said further: One should not sound a shofar that was used for idol worship, but if he nevertheless transgressed and sounded it, he has fulfilled his obligation. One should also not sound a shofar from a city whose residents were incited to idolatry, where the majority of inhabitants committed idolatry, but if he nevertheless transgressed and sounded it, he has not fulfilled his obligation. What is the reason for this last ruling? With regard to any object found in a city whose residents were incited to idolatry, its size as required for the mitzva is seen by halakha as crushed into powder. Since a shofar from a city whose residents were incited to idolatry is destined for burning, it is considered as if it is already burnt, and it therefore lacks the requisite measurement for fulfilling the mitzva.

אָמַר רָבָא: הַמּוּדָּר הֲנָאָה מֵחֲבֵירוֹ — מוּתָּר לִתְקוֹעַ לוֹ תְּקִיעָה שֶׁל מִצְוָה. הַמּוּדָּר הֲנָאָה מִשּׁוֹפָר — מוּתָּר לִתְקוֹעַ בּוֹ תְּקִיעָה שֶׁל מִצְוָה.

Rava said: If one is prohibited by vow from deriving benefit from another, i.e., if he took a vow not to receive any benefit whatsoever from a certain person, that other person is nevertheless permitted to sound a blast for him so that he fulfills the mitzva, in accordance with the principle that the fulfillment of a mitzva is not in itself considered a benefit. For the same reason, if one is prohibited by vow from deriving benefit from a particular shofar, he is nevertheless permitted to sound a blast with it so that he may fulfill the mitzva.

וְאָמַר רָבָא: הַמּוּדָּר הֲנָאָה מֵחֲבֵירוֹ — מַזֶּה עָלָיו מֵי חַטָּאת בִּימוֹת הַגְּשָׁמִים, אֲבָל לֹא בִּימוֹת הַחַמָּה. הַמּוּדָּר הֲנָאָה מִמַּעְיָן — טוֹבֵל בּוֹ טְבִילָה שֶׁל מִצְוָה בִּימוֹת הַגְּשָׁמִים, אֲבָל לֹא בִּימוֹת הַחַמָּה.

And Rava said further: If one is prohibited by vow from deriving benefit from another, that other person may nevertheless sprinkle the waters of purification on him, i.e., water mixed with the ashes of the red heifer, which was used to purify people and objects that had contracted ritual impurity through contact with a corpse, in the rainy season, for at that time the sprinkling is performed only in order to fulfill a mitzva. But he may not do so in the summer season, since then he also benefits from the very fact that water is being sprinkled on him. Similarly, if one is prohibited by vow from deriving benefit from a particular spring, he may nevertheless immerse in it an immersion performed in order to fulfill a mitzva in the rainy season, but not in the summer season, since then he also derives benefit from the very fact that he has immersed in cold water.

שְׁלַחוּ לֵיהּ לַאֲבוּהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל: כְּפָאוֹ וְאָכַל מַצָּה — יָצָא. כְּפָאוֹ מַאן? אִילֵימָא כְּפָאוֹ שֵׁד, וְהָתַנְיָא: עִתִּים חָלִים עִתִּים שׁוֹטֶה, כְּשֶׁהוּא חָלִים — הֲרֵי הוּא כְּפִקֵּחַ לְכׇל דְּבָרָיו, כְּשֶׁהוּא שׁוֹטֶה — הֲרֵי הוּא כְּשׁוֹטֶה לְכׇל דְּבָרָיו!

§ It is related that the following ruling was sent from Eretz Yisrael to Shmuel’s father: If one was forcibly compelled to eat matza on Passover, he has fulfilled his obligation. The Gemara clarifies the matter: Who compelled him to eat the matza? If we say that a demon forced him, i.e., that he ate it in a moment of insanity, this is difficult. Isn’t it taught in a baraita: With regard to someone who is at times sane and at times insane, at the times when he is sane, he is considered halakhically competent for all purposes and is obligated in all the mitzvot. And when he is insane, he is considered insane for all purposes, and is therefore exempt from the mitzvot. If so, someone who was compelled by a demon to eat matza is not considered obligated to perform the mitzvot at all.

אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: שֶׁכְּפָאוּהוּ פָּרְסִיִּים. אָמַר רָבָא, זֹאת אוֹמֶרֶת: הַתּוֹקֵעַ לָשִׁיר — יָצָא.

Rav Ashi said: We are dealing with a case where the Persians compelled him to eat. Rava said: That is to say that one who sounds a shofar for the music, having no intent to fulfill the mitzva, fulfills his obligation, since the critical issue is hearing the blast and not the intent of the blower.

פְּשִׁיטָא, הַיְינוּ הָךְ! מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: הָתָם, אֱכוֹל מַצָּה אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא — וְהָא אֲכַל,

The Gemara asks: Isn’t it obvious that this is identical to that which was stated above, that one who was compelled to eat matza fulfills the mitzva even if he had no intention of doing so? The same should apply in the case of the shofar, that one who heard the blast of a shofar fulfills his obligation even if he had no intention of doing so. The Gemara answers: Lest you say that there is a difference between the two cases, there, the Merciful One says: Eat matza, and he indeed ate it, thereby fulfilling the mitzva.

אֲבָל הָכָא, ״זִכְרוֹן תְּרוּעָה״ כְּתִיב, וְהַאי מִתְעַסֵּק בְּעָלְמָא הוּא — קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן. אַלְמָא קָסָבַר רָבָא: מִצְוֹת אֵין צְרִיכוֹת כַּוָּונָה.

But here, with regard to a shofar, it is written: “A memorial of blasts” (Leviticus 23:24), which might have been understood as requiring conscious intent, and this one was merely acting unawares, without having any intent whatsoever of performing the mitzva. Therefore, Rava teaches us that the absence of intent does not invalidate fulfillment of the mitzva, even in the case of shofar. The Gemara concludes: Apparently, Rava maintains that the fulfillment of mitzvot does not require intent. That is to say, if one performs a mitzva, he fulfills his obligation even if he has no intention of doing so.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ: הָיָה קוֹרֵא בַּתּוֹרָה וְהִגִּיעַ זְמַן הַמִּקְרָא, אִם כִּוֵּון לִבּוֹ — יָצָא, וְאִם לָאו — לֹא יָצָא. מַאי לָאו, כִּוֵּון לִבּוֹ: לָצֵאת!

The Gemara raised an objection to this conclusion from what we learned in a mishna: If one was reading the passage of Shema in the Torah, and the time of reciting Shema arrived, if he focused his heart, he has fulfilled his obligation, but if not, he has not fulfilled his obligation. The Gemara reasons: What, is it not that he focused his heart to fulfill his obligation, and if he failed to do so, he has not fulfilled his duty, therefore implying that the fulfillment of mitzvot requires intent?

לֹא: לִקְרוֹת. לִקְרוֹת?! הָא קָא קָרֵי! בְּקוֹרֵא לְהַגִּיהַּ.

The Gemara rejects this argument: No, the mishna means that he intended to read the passage. The Gemara asks in astonishment: To read? But he is already reading it, for the mishna explicitly states: If one was reading in the Torah. The Gemara answers: We are discussing one who was reading from a Torah scroll in order to correct it, uttering the words indistinctly. The mishna teaches that if such an individual intends to articulate the words correctly, he has fulfilled his obligation.

תָּא שְׁמַע: הָיָה עוֹבֵר אֲחוֹרֵי בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת, אוֹ שֶׁהָיָה בֵּיתוֹ סָמוּךְ לְבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת, וְשָׁמַע קוֹל שׁוֹפָר אוֹ קוֹל מְגִילָּה, אִם כִּוֵּון לִבּוֹ — יָצָא, וְאִם לָאו — לֹא יָצָא. מַאי לָאו, אִם כִּוֵּון לִבּוֹ לָצֵאת?

The Gemara raises another objection: Come and hear that which we learned in our mishna: If one was passing behind a synagogue, or his house was adjacent to the synagogue, and he heard the sound of the shofar or the sound of the Scroll of Esther, if he focused his heart, he has fulfilled his obligation, but if not, he has not fulfilled his obligation. What, is it not that he focused his heart to fulfill his obligation, and if he failed to do so, he has not fulfilled his duty, therefore implying that the fulfillment of mitzvot requires intent?

לֹא — לִשְׁמוֹעַ. לִשְׁמוֹעַ?! וְהָא שָׁמַע! סְבוּר, חֲמוֹר בְּעָלְמָא הוּא.

The Gemara rejects this argument: No, the mishna means that he intended to hear the sound of the shofar. The Gemara immediately asks: To hear? But he already hears it, since the mishna explicitly states: And he heard the sound of the shofar. The Gemara answers: We are discussing one who thinks that it is merely the sound of a donkey that he is hearing, and in this case, where the listener thinks that the sound was not that of a shofar, he does not fulfill his obligation. Therefore, the mishna teaches that it is sufficient that one have intent and know that he is hearing the sound of a shofar.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ: נִתְכַּוֵּון שׁוֹמֵעַ וְלֹא נִתְכַּוֵּון מַשְׁמִיעַ, מַשְׁמִיעַ וְלֹא נִתְכַּוֵּון שׁוֹמֵעַ — לֹא יָצָא, עַד שֶׁיִּתְכַּוֵּון שׁוֹמֵעַ וּמַשְׁמִיעַ. בִּשְׁלָמָא נִתְכַּוֵּון מַשְׁמִיעַ וְלֹא נִתְכַּוֵּון שׁוֹמֵעַ — כְּסָבוּר חֲמוֹר בְּעָלְמָא הוּא, אֶלָּא נִתְכַּוֵּון שׁוֹמֵעַ וְלֹא נִתְכַּוֵּון מַשְׁמִיעַ — הֵיכִי מַשְׁכַּחַתְּ לַהּ? לָאו בְּתוֹקֵעַ לָשִׁיר!

The Gemara raised an objection to this answer from a baraita: If the hearer of the shofar had intent, but the sounder of the shofar did not have intent, or if the sounder of the shofar had intent, but the hearer did not have intent, he has not fulfilled his obligation, until both the hearer and the sounder have intent. Granted, with regard to the case where the sounder had intent, but the hearer did not have intent, Rava can say that this is referring to a case where the hearer thinks that it is merely the sound of a donkey and he did not have intent to hear the sound of a shofar. But with regard to the case where the hearer had intent, but the sounder did not have intent, under what circumstances can this case be found? Is it not where he sounds a shofar for music and despite the intent of the hearer he has not fulfilled his obligation? This implies that unless the sounder of the shofar has intent to fulfill the mitzva the hearer does not fulfill his obligation.

דִּלְמָא דְּקָא מְנַבַּח נַבּוֹחֵי.

The Gemara rejects this argument: Perhaps the baraita is referring to a case where he sounded bark-like blasts with the shofar, i.e., he did not sound the shofar in the proper manner, but merely acted unawares without intent to perform the mitzva. The baraita teaches us that if he has intent to sound the blasts in the correct manner, he has fulfilled his obligation.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: אֶלָּא מֵעַתָּה, הַיָּשֵׁן בַּשְּׁמִינִי בַּסּוּכָּה — יִלְקֶה!

Abaye said to Rava: However, if that is so, that the fulfillment of a mitzva does not require intent, one who sleeps in a sukka on the Eighth Day of Assembly should receive lashes for violating the prohibition against adding to mitzvot, since he is adding to the mitzva of: “You shall dwell in sukkot for seven days” (Leviticus 23:42). Since, according to Rava, even if one did not intend to observe the mitzva of sukka but slept in the sukka for a different reason, his sleeping in the sukka constitutes the fulfillment of a mitzva to dwell there, then, if one did so at an inappropriate time, he is considered to have transgressed the prohibition against adding to the mitzvot. Yet the Sages instituted that in the Diaspora one must observe Sukkot for eight days.

אָמַר לוֹ, שֶׁאֲנִי אוֹמֵר: מִצְוֹת אֵינוֹ עוֹבֵר עֲלֵיהֶן אֶלָּא בִּזְמַנָּן.

Rava said to him: This is because I say that mitzvot can be transgressed only by adding to them in their prescribed times. But if one adds to a mitzva outside of the period of obligation for the mitzva, there is no violation of the prohibition against adding to mitzvot. On the Eighth Day of Assembly there is no longer a mitzva to sleep in the sukka. Therefore, sleeping in the sukka on that day does not constitute a prohibited act.

מֵתִיב רַב שֶׁמֶן בַּר אַבָּא: מִנַּיִן לְכֹהֵן שֶׁעוֹלֶה לַדּוּכָן, שֶׁלֹּא יֹאמַר: הוֹאִיל וְנָתְנָה לִי תּוֹרָה רְשׁוּת לְבָרֵךְ אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל אוֹסִיף בְּרָכָה אַחַת מִשֶּׁלִּי, כְּגוֹן: ״ה׳ אֱלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵיכֶם יוֹסֵף עֲלֵיכֶם״ — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״לֹא תוֹסִיפוּ עַל הַדָּבָר״. וְהָא הָכָא, כֵּיוָן דְּבָרֵיךְ לֵיהּ — עָבְרָה לֵיהּ זִמְנֵיהּ, וְקָתָנֵי דְּעָבַר!

Rav Shemen bar Abba raised an objection from that which was taught in a baraita: From where is it derived that a priest who went up to the platform to recite the Priestly Blessing should not say: Since the Torah granted me permission to bless the Jewish people, I will add a blessing of my own, which is not part of the Priestly Blessing stated in the Torah, for example: “May the Lord God of your fathers make you a thousand times as many as you are” (Deuteronomy 1:11)? It is derived from the verse that states: “You shall not add to the word which I command you” (Deuteronomy 4:2). But here, since the priest already recited the Priestly Blessing, the time of the mitzva has passed, and according to Rava, after the prescribed time for performing a mitzva, one does not transgress the prohibition against adding to mitzvot, yet it nevertheless teaches that he has transgressed.

הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן — בִּדְלָא סַיֵּים.

The Gemara answers: With what are we dealing here? With a case where he did not complete the fixed text of the blessing but added to it in the middle.

וְהָתַנְיָא סִיֵּים! סִיֵּים בְּרָכָה אַחַת.

The Gemara raises an objection: Isn’t it taught explicitly in a parallel baraita: If he completed the Priestly Blessing. The Gemara answers: The baraita means that he completed one blessing, i.e., the first verse of the Priestly Blessing, but he still has two more blessings to recite.

וְהָתַנְיָא: סִיֵּים כׇּל בִּרְכוֹתָיו! שָׁאנֵי הָכָא, כֵּיוָן דְּאִלּוּ מִתְרְמֵי לֵיהּ צִבּוּרָא אַחֲרִינָא, הָדַר מְבָרֵךְ — כּוּלֵּיהּ יוֹמָא זִמְנֵיהּ הוּא.

The Gemara raises a further difficulty: Isn’t it taught in another baraita dealing with the same issue: If he completed all of his blessings. The Gemara explains: Here, with regard to the Priestly Blessings, it is different, since if he encounters another congregation, he may recite the blessings again, from which we learn that the entire day is the prescribed time of the mitzva. Therefore, even if he added a blessing of his own only after he finished reciting all three verses of the Priestly Blessing, he is still considered to have added to the mitzva in its prescribed time, and he therefore transgresses the prohibition against adding to mitzvot.

וּמְנָא תֵּימְרָא — דִּתְנַן: הַנִּיתָּנִין בְּמַתָּנָה אַחַת, שֶׁנִּתְעָרְבוּ בַּנִּיתָּנִין מַתָּנָה אַחַת — יִנָּתְנוּ מַתָּנָה אַחַת. מַתַּן אַרְבַּע בְּמַתַּן אַרְבַּע — יִנָּתְנוּ בְּמַתַּן אַרְבַּע.

The Gemara comments: And from where do you say that if a mitzva may be performed again, the whole day is considered its prescribed time? As we learned in a mishna: If the blood of sacrifices that require only one sprinkling, such as the firstborn offering, became mingled with the blood of other sacrifices that require only one sprinkling, the mixture of blood is sprinkled once. Similarly, if the blood of sacrifices that require four sprinklings, such as burnt-offerings, became mingled with the blood of other sacrifices that require four sprinklings, the mixture is sprinkled four times.

מַתַּן אַרְבַּע בְּמַתַּן אַחַת, רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: יִנָּתְנוּ בְּמַתַּן אַרְבַּע, רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אוֹמֵר: יִנָּתְנוּ בְּמַתַּן אַחַת.

However, if the blood of an offering that requires four sprinklings became mingled with the blood of an offering that requires only one sprinkling, the tanna’im disagree: Rabbi Eliezer says: The mixture of blood is sprinkled four times. And Rabbi Yehoshua says: It is sprinkled once.

אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר: הֲרֵי הוּא עוֹבֵר עַל ״בַּל תִּגְרַע״! אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ: הֲרֵי הוּא עוֹבֵר עַל ״בַּל תּוֹסִיף״!

Rabbi Eliezer said to Rabbi Yehoshua: But if he sprinkles the blood only once, he thereby transgresses the prohibition: Do not diminish, which renders it prohibited to take away any element in the performance of a mitzva, as he has not sprinkled the blood of an offering requiring four sprinklings, i.e., the burnt-offering in the proper manner. Rabbi Yehoshua said to Rabbi Eliezer: But according to your position, that he must sprinkle the blood four times, he thereby transgresses the prohibition: Do not add, which renders it prohibited to add elements to a mitzva, e.g. an offering requiring one sprinkling, like the firstborn animal.

אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר: לֹא נֶאֱמַר ״בַּל תּוֹסִיף״ אֶלָּא כְּשֶׁהוּא בְּעַצְמוֹ. אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ: לֹא נֶאֱמַר ״בַּל תִּגְרַע״ אֶלָּא כְּשֶׁהוּא בְּעַצְמוֹ.

Rabbi Eliezer said to Rabbi Yehoshua: The prohibition: Do not add, is stated only in a case where the blood stands by itself, but not when it is part of a mixture. Rabbi Yehoshua said to Rabbi Eliezer: Likewise, the prohibition: Do not diminish, is stated only in a case where the blood stands by itself.

וְעוֹד אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ: כְּשֶׁלֹּא נָתַתָּ — עָבַרְתָּ עַל ״בַּל תִּגְרַע״ וְלֹא עָשִׂיתָ מַעֲשֶׂה בְּיָדֶךָ, כְּשֶׁנָּתַתָּ — עָבַרְתָּ עַל ״בַּל תּוֹסִיף״ וְעָשִׂיתָ מַעֲשֶׂה בְּיָדֶךָ.

Rabbi Yehoshua said further, in defense of his position: When you do not sprinkle four times, even if you transgress the prohibition: Do not diminish, you do not perform the act with your own hand, since it is merely an omission, not an action. Whereas when you sprinkle four times, you transgress the prohibition: Do not add, with regard to one of the sacrifices, and you perform the act with your own hand, i.e., you transgress the Torah’s command by means of a positive act. If one is forced to deviate from the words of the Torah, it is preferable to do so in a passive manner. The Gemara concludes the citation from the mishna.

וְהָא הָכָא, כֵּיוָן דְּיָהֵיב לֵיהּ מַתָּנָה מִבְּכוֹר — עָבְרָה לֵיהּ לְזִמְנֵיהּ, וְקָתָנֵי דְּעָבַר מִשּׁוּם ״בַּל תּוֹסִיף״. לָאו מִשּׁוּם דְּאָמְרִינַן: כֵּיוָן דְּאִילּוּ מִתְרְמֵי לֵיהּ בּוּכְרָא אַחֲרִינָא — הָדַר מַזֶּה מִינֵּיהּ, כּוּלֵּיהּ יוֹמָא זִמְנֵיהּ?!

The Gemara proceeds to derive from here that if the mitzva may be performed again the whole day is considered its prescribed time: And here, once he has already offered one sprinkling of the blood of the firstborn as required, its time has passed, since he has already completed the mitzva of sprinkling the blood of the firstborn, and it nevertheless teaches that he transgresses the prohibition: Do not add. Is it not because we say as follows: Since if he encounters another firstborn to be sacrificed, he would sprinkle of its blood again? If so, the entire day is considered the prescribed time for the mitzva of sprinkling.

מִמַּאי? דִּלְמָא קָסָבַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ מִצְוֹת עוֹבֵר עֲלֵיהֶן אֲפִילּוּ שֶׁלֹּא בִּזְמַנָּן.

The Gemara rejects this argument: From where do you conclude that this is so? Perhaps Rabbi Yehoshua maintains that mitzvot can be transgressed by adding to them even outside their prescribed times. Therefore, this source provides no proof.

אֲנַן הָכִי קָאָמְרִינַן: רַב שֶׁמֶן בַּר אַבָּא מַאי טַעְמָא שָׁבֵיק מַתְנִיתִין וּמוֹתֵיב מִבָּרַיְיתָא, לוֹתֵיב מִמַּתְנִיתִין! מַתְנִיתִין מַאי טַעְמָא לָא מוֹתֵיב? כֵּיוָן דְּאִילּוּ מִתְרְמֵי לֵיהּ בּוּכְרָא אַחֲרִינָא בָּעֵי מַזֶּה מִינֵּיהּ — כּוּלֵּיהּ יוֹמָא זִמְנֵיהּ הוּא, בָּרַיְיתָא נָמֵי, כֵּיוָן דְּאִי מִתְרְמֵי צִבּוּרָא אַחֲרִינָא הָדַר מְבָרֵךְ — כּוּלֵּיהּ יוֹמָא זִמְנֵיהּ.

The Gemara explains: This is what we were saying when we cited this mishna: What is the reason that Rav Shemen bar Abba set aside the mishna, which deals with the sprinkling of blood, and raised an objection from a baraita? He should have raised an objection from the mishna, which is more generally accepted. What is the reason that he does not raise an objection from the mishna? Since he knows that it can be argued as follows: Because if he encounters another firstborn he will be required to sprinkle its blood. Therefore the entire day is considered the prescribed time of the mitzva. If so, with regard to the baraita as well, it can be argued that because if he encounters another congregation, he may recite the Priestly Blessing again, the whole day is considered its prescribed time.

וְרַב שֶׁמֶן בַּר אַבָּא? הָתָם, לָא סַגִּי דְּלָא יָהֵיב. הָכָא, אִי בָּעֵי — מְבָרֵךְ, אִי בָּעֵי — לָא מְבָרֵךְ.

The Gemara asks: And what is the opinion of Rav Shemen bar Abba, who raised the objection from the baraita? The Gemara explains: There, it is not possible to refrain from sprinkling the blood of another firstborn that comes his way, so the entire day is certainly its prescribed time. But here, if he wishes, he may bless the other congregation, and if he wishes, he may refrain from blessing them, since he is obligated to recite the Priestly Blessing only once a day.

רָבָא אָמַר, לָצֵאת — לָא בָּעֵי כַּוָּונָה, לַעֲבוֹר — בָּעֵי כַּוָּונָה.

Rava himself said: There is no difficulty at all, since the fulfillment of a mitzva does not require intent, but the transgression of the prohibition: Do not add, or: Do not diminish, requires intent.

וְהָא מַתַּן דָּמִים לְרַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ, דְּלַעֲבוֹר וְלָא בָּעֵי כַּוָּונָה! אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבָא: לָצֵאת — לָא בָּעֵי כַּוָּונָה. לַעֲבוֹר, בִּזְמַנּוֹ — לָא בָּעֵי כַּוָּונָה, שֶׁלֹּא בִּזְמַנּוֹ — בָּעֵי כַּוָּונָה.

The Gemara raises a difficulty: But in the case of the sprinkling of blood, according to Rabbi Yehoshua, the transgression of the prohibition: Do not add, does not require intent, since he holds that if one added to the required sprinklings, he transgresses. Rather, Rava said: One must say as follows: The fulfillment of a mitzva does not require intent, and the transgression of the prohibition: Do not add, during the prescribed time of the mitzva, does not require intent, and the sprinkler of the blood therefore transgresses, as Rabbi Yehoshua maintains. However, the transgression of the prohibition: Do not add, when it is not in its prescribed time, e.g., in the case of sleeping in the sukka on the Eighth Day of Assembly, requires intent to fulfill the mitzva, and in the absence of such intent, there is no transgression.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַבִּי זֵירָא לְשַׁמָּעֵיהּ:

With regard to the intent required in order to fulfill the mitzva of shofar, Rabbi Zeira said to his servant: