The gemara concludes the questions regarding various methods of extrapolations – whether one can learn one and then another in the realm of kodashim. The verses mentioning pouring the extra blood into the base of the altar are extrapolated.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

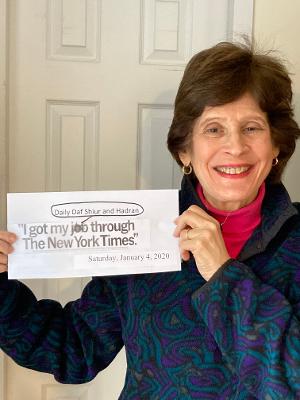

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Zevachim 51

מְטַהֶרֶת טְרֵיפָתָהּ מִטּוּמְאָתָהּ; אַף מְלִיקָה, שֶׁמַּכְשַׁרְתָּהּ בַּאֲכִילָה – תְּטַהֵר טְרֵיפָתָהּ מִטּוּמְאָתָהּ.

and it purifies its tereifa from its impurity, so too its pinch-ing, which permits bird offerings with regard to consumption, should purify its tereifa from its impurity.

רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: דַּיָּהּ כְּנִבְלַת בְּהֵמָה טְהוֹרָה – שֶׁשְּׁחִיטָתָהּ מְטַהַרְתָּהּ, וְלֹא מְלִיקָתָהּ.

Rabbi Yosei says: Although one can derive from the case of an animal that slaughter purifies the tereifa of a bird from its impurity, that derivation cannot be extended to pinching. The same restriction that applies to every a fortiori inference, namely, that a halakha derived by means of an a fortiori inference is no more stringent than the source from which it is derived, applies here: It is sufficient for the halakhic status of the carcass of a bird that is a tereifa to be like that of the carcass of an animal of a kosher species that is a tereifa; i.e., that only its slaughter purifies it, but not its pinching.

וְלָא הִיא; הָתָם תֶּיהְוֵי הִיא, מִשְּׁחִיטָה דְּחוּלִּין קָאָתְיָין.

The Gemara rejects this proof: And that is not so. Let it remain there, i.e., one cannot learn from it, as that is a case that comes from the slaughter of non-sacred animals. The halakha of the pinching of a consecrated bird is derived through a paradigm from the halakha of the slaughter of a non-sacred bird, and the halakha of the slaughter of a non-sacred bird is derived through an a fortiori inference from the halakha of the slaughter of a non-sacred animal. Outside of the realm of consecrated matters there is no question that a matter derived via one of the hermeneutical principles can then teach its halakha via another principle. The entire question under discussion is only with regard to the realm of consecrated matters.

דָּבָר הַלָּמֵד בְּבִנְיַן אָב, מַהוּ שֶׁיְּלַמֵּד בְּהֶיקֵּשׁ וּבִגְזֵירָה שָׁוָה וּבְקַל וָחוֹמֶר וּבְבִנְיַן אָב?

§ The Gemara asks: What is the halakha as to whether a matter derived via a paradigm can teach its halakha to another matter via a juxtaposition or via a verbal analogy or via an a fortiori inference or via a paradigm?

פְּשׁוֹט מִיהָא חֲדָא – מִפְּנֵי מָה אָמְרוּ: לָן בַּדָּם – כָּשֵׁר? שֶׁהֲרֵי לָן בָּאֵימוּרִין כָּשֵׁר. לָן בְּאֵימוּרִין כָּשֵׁר – שֶׁהֲרֵי לָן בַּבָּשָׂר כָּשֵׁר.

The Gemara states: Resolve at least one of those questions. The Gemara cites a lengthy baraita before stating the resolution inferred from that baraita. For what reason did the Sages say that in the case of blood left overnight it is fit, i.e., if blood of an offering had been left overnight and was then placed on the altar it need not be removed? This is as it is in the case of sacrificial portions, where if they are left overnight they are fit. From where is it derived that in the case of sacrificial portions which are left overnight, they are fit? This is as it is in the case of meat, where if it is left overnight it is fit, because the meat of a peace offering may be eaten for two days and one night.

יוֹצֵא – הוֹאִיל וְיוֹצֵא כָּשֵׁר בְּבָמָה.

From where is it derived that if an offering that has left the Temple courtyard is then placed on the altar it need not be removed? This is derived by a paradigm, since an offering that leaves its area is fit in the case of an offering brought on a private altar.

טָמֵא – הוֹאִיל וְהוּתַּר בַּעֲבוֹדַת צִיבּוּר.

From where is it derived that if an offering that has become ritually impure is placed on the altar it need not be removed? This is derived by a paradigm, since one is permitted to offer an impure offering in the case of communal rites, i.e., communal offerings. In cases of necessity, the communal offerings may be sacrificed even if they are ritually impure.

חוּץ לִזְמַנּוֹ – הוֹאִיל וּמְרַצֶּה לְפִיגּוּלוֹ.

From where is it derived that in the case of an offering that was disqualified due to the intention of the priest who slaughtered it to consume it beyond its designated time [piggul], if it was placed on the altar it need not be removed? The halakha applies there since the sprinkling of its blood effects acceptance of the offering notwithstanding its status of piggul. The status of piggul takes effect only if the sacrificial rites involving that offering were otherwise performed properly. This indicates that it still has the status of an offering, so it need not be removed from the altar.

חוּץ לִמְקוֹמוֹ – הוֹאִיל וְהוּקַּשׁ לְחוּץ לִזְמַנּוֹ.

From where is it derived that in the case of an offering that was disqualified due to the intention of the priest who slaughtered it to consume it outside its designated area, if it was placed on the altar it need not be removed? This is derived by a paradigm, since it is juxtaposed to an offering that was slaughtered with intent to consume it beyond its designated time.

שֶׁקִּיבְּלוּ פְּסוּלִין וְזָרְקוּ דָּמָן – בְּהָנָךְ פְּסוּלִין דַּחֲזוּ לַעֲבוֹדַת צִיבּוּר.

From where is it derived that in the case of an offering for which priests who are disqualified collected and sprinkled its blood, if it was placed on the altar it need not be removed? This is derived from the halakha of these priests who are generally disqualified because they are impure, yet who are fit to perform the communal rites, i.e., to sacrifice communal offerings, when all the priests or the majority of the Jewish people are impure. In any event, the halakha of the sacrificial portions was derived via a paradigm from the halakha of meat that was left overnight, and then the halakha of blood was derived via a paradigm from the halakha of the sacrificial portions. Evidently, a matter derived via a paradigm can teach its halakha to another matter via a paradigm.

וְכִי דָּנִין דָּבָר שֶׁלֹּא בְּהֶכְשֵׁירוֹ, מִדָּבָר שֶׁבְּהֶכְשֵׁירוֹ?!

The Gemara questions the derivations of the baraita: But can one deduce the halakha of a matter that is not fit, i.e., sacrificial portions that are disqualified due to having been left overnight, from the halakha of a matter that is fit, i.e., the peace offering, which is permitted to be eaten for two days and one night? Similarly, how can the baraita derive the halakha of meat that was removed from the Temple courtyard from the halakha of a private altar, which has no sacred area surrounding it?

תַּנָּא מִ״זֹּאת תּוֹרַת הָעוֹלָה״ רִיבָּה סָמֵיךְ לֵיהּ.

The Gemara answers: The tanna relied on the verse: “Command Aaron and his sons, saying: This is the law of the burnt offering: It is that which goes up on its firewood upon the altar all night until the morning; and the fire of the altar shall thereby be kept burning” (Leviticus 6:2), which amplified it, teaching that many types of disqualified offerings may be left upon the altar. The derivations written in the baraita are mere supports for those halakhot.

שְׁיָרֵי הַדָּם כּוּ׳. מַאי טַעְמָא? אָמַר קְרָא: ״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבַּח הָעֹלָה אֲשֶׁר פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד״ – הַהוּא דְּפָגַע בְּרֵישָׁא.

§ The mishna teaches with regard to the sin offerings whose blood is presented inside the Sanctuary: As to the remainder of the blood which is left after the sprinklings, a priest would pour it onto the western base of the external altar. But if he did not place the remainder of the blood on the western base, it does not disqualify the offering. The Gemara asks: What is the reason that it must be poured on the western base? The Gemara answers: The verse states with regard to the bull offering of the High Priest: “And the priest shall sprinkle the blood upon the corners of the altar of sweet incense before the Lord, which is in the Tent of Meeting; and all the remaining blood of the bull he shall pour out at the base of the altar of burnt offering, which is at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (Leviticus 4:7). This means that he must pour it on that base which he encounters first when he leaves the Tent of Meeting, which is the western base.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבַּח הָעֹלָה״ – וְלֹא יְסוֹד מִזְבֵּחַ הַפְּנִימִי.

The Sages taught in a baraita: There are three verses that contain the same phrase. With regard to pouring the remainder of the blood of a bull offering of the High Priest, the verse states: “All the remaining blood of the bull he shall pour out at the base of the altar of burnt offering” (Leviticus 4:7). This teaches that it must be on the base of the external altar, but not on the base of the inner altar, where he had sprinkled the blood.

״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבַּח הָעֹלָה״ – אֵין לוֹ יְסוֹד לַפְּנִימִי עַצְמוֹ.

The baraita continues: With regard to the bull sacrificed for an unwitting communal sin the verse states: “And he shall sprinkle the blood upon the corners of the altar which is before the Lord, that is in the Tent of Meeting, and all the remaining blood shall he pour out at the base of the altar of burnt offering, which is at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (Leviticus 4:18). This teaches that the inner altar itself has no base at all.

״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבַּח הָעֹלָה״ – תֵּן יְסוֹד לַמִּזְבֵּחַ שֶׁל עוֹלָה.

Finally, the verse states with regard to the sin offering of a king: “And the priest shall take of the blood of the sin offering with his finger and place it upon the corners of the altar of burnt offering, and the remaining blood thereof shall he pour out at the base of the altar of the burnt offering” (Leviticus 4:25). This teaches that you must give a base to the altar of the burnt offering, i.e., that the remainder of any blood placed on the altar must be poured on the base.

אוֹ אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא מִזְבְּחָהּ שֶׁל עוֹלָה – יְהֵא לַיְסוֹד? אָמַר רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל: קַל וָחוֹמֶר; מָה שִׁירַיִים, שֶׁאֵין מְכַפְּרִין – טְעוּנִין יְסוֹד; תְּחִלַּת עוֹלָה, שֶׁמְּכַפֶּרֶת – אֵינוֹ דִּין שֶׁטְּעוּנָה יְסוֹד?!

The baraita continues: Or perhaps it is not so, but rather the verse serves to teach that any sprinkling of blood on the corners of the altar of the burnt offering will be done on a part of the altar where there is a base. Rabbi Yishmael said: There is no need for the verse to teach that halakha, because it can be derived via an a fortiori inference: Just as the remainder of the blood, which does not effect atonement, requires pouring on the base of the altar, with regard to the initial sprinkling of the blood of a burnt offering, which effects atonement, is it not logical that it requires a part of the altar where there is a base?

אָמַר רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא: מָה שִׁירַיִים, שֶׁאֵין מְכַפְּרִין וְאֵין בָּאִין לְכַפָּרָה – טְעוּנָה יְסוֹד; תְּחִלַּת עוֹלָה, שֶׁמְּכַפֶּרֶת וּבָאָה לְכַפָּרָה – אֵינוֹ דִּין שֶׁטְּעוּנָה יְסוֹד?

Similarly, Rabbi Akiva said: Just as the remainder of the blood, which does not effect atonement and does not come for atonement, nevertheless requires pouring on the base of the altar, with regard to the initial sprinkling of the blood of a burnt offering, which effects atonement and comes for atonement, is it not logical that it requires a part of the altar where there is a base?

אִם כֵּן, מָה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבַּח הָעֹלָה״? תֵּן יְסוֹד לְמִזְבְּחָהּ שֶׁל עוֹלָה.

The baraita concludes: If so, why must the verse state: “At the base of the altar of burnt offering” (Leviticus 4:25)? It is to teach that you must give a base to the altar of the burnt offering, i.e., that the remainder of the blood of the offering must be poured on the base.

אָמַר מָר: ״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבֵּחַ״ – וְלֹא יְסוֹד מִזְבֵּחַ הַפְּנִימִי. הָא מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְגוּפֵיהּ! מֵ״אֲשֶׁר פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד״ נָפְקָא.

The Gemara discusses this baraita. The Master says: The verse states: “At the base of the altar of burnt offering, which is at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (Leviticus 4:18). This teaches that it must be on the base of the external altar, but not the base of the inner altar. The Gemara asks: Isn’t that necessary for the matter itself, to teach that the remainder of the blood must be poured onto the base of the external altar? The Gemara answers: That halakha is derived from: “Which is at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (Leviticus 4:18), referring to the external altar. Therefore, the verse mentions the altar of burnt offering to exclude the base of the inner altar.

״אֶל יְסוֹד מִזְבַּח הָעוֹלָה״ –

The baraita teaches with regard to the sin offering of a king: The verse states: “And the priest shall take of the blood of the sin offering with his finger, and place it upon the corners of the altar of burnt offering, and the remaining blood thereof shall he pour out at the base of the altar of burnt offering” (Leviticus 4:25).

תֵּן יְסוֹד לַמִּזְבֵּחַ שֶׁל עוֹלָה.

This teaches that you must give a base to the altar of the burnt offering, i.e., that the remainder of any blood placed on the altar must be poured on the base.

דְּאִי סָלְקָא דַעְתָּךְ כְּדִכְתִיב; הָנֵי לְמָה לִי קְרָא – לְשִׁירַיִם?! שִׁירַיִם הָא בָּרַאי עָבֵיד לְהוּ!

The Gemara explains: Because if it enters your mind that the verse states this simply to teach as it is written, concerning this offering alone, why do I need these verses with regard to the sin offering of a king? If you would answer: The verses are needed to teach the halakha that the remainder of the blood must be poured on the external altar rather than on the inner altar, then the question remains: Is there any need for the Torah to teach this about the remainder? But the sprinklings of blood themselves are performed on the external altar, so why would one think that the remainder of the blood should be poured on the inner altar?

וְכִי תֵּימָא דְּאָפֵיךְ מֵיפָךְ –

And if you would say that one might mistakenly say that the priest reverses the sprinklings,