Arakhin 7

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

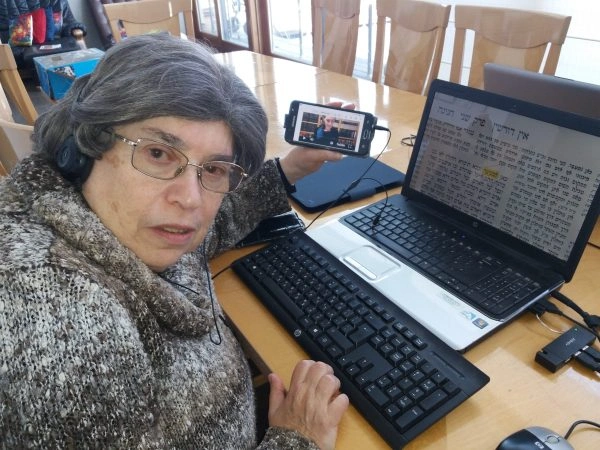

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Arakhin 7

מִכְּלָל דְּתַנָּא קַמָּא סָבַר: נִיתַּן לַחֲזָרַת עֲמִידַת בֵּית דִּין?!

The Gemara asks: If so, can one conclude by inference that the first tanna holds that one who is being taken to be executed can be brought back to stand before the court for judgment? This is clearly erroneous, as the court is not permitted to delay his execution.

אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: בְּמִלְוָה עַל פֶּה גּוֹבֶה מִן הַיּוֹרְשִׁין קָמִיפַּלְגִי, תַּנָּא קַמָּא סָבַר: מִלְוָה עַל פֶּה גּוֹבֶה מִן הַיּוֹרְשִׁין, וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר סָבַר: אֵינוֹ גּוֹבֶה מִן הַיּוֹרְשִׁין.

Rav Yosef says: Everyone agrees that his execution may not be delayed. Rather, they disagree as to whether or not one who is owed money from a loan by oral agreement can collect from the heirs. The first tanna holds that one who is owed money from a loan by oral agreement can collect from the heirs, and therefore the injured party can collect from the heirs after the execution. But Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar holds that one who is owed money from a loan by oral agreement cannot collect from the heirs, and therefore the heirs are exempt from payment for the injury.

רַבָּה אָמַר: דְּכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא מִלְוָה עַל פֶּה אֵינוֹ גּוֹבֶה מִן הַיּוֹרְשִׁין, וְהָכָא בְּמִלְוָה הַכְּתוּבָה בַּתּוֹרָה כִּכְתוּבָה בִּשְׁטָר קָמִיפַּלְגִי, תַּנָּא קַמָּא סָבַר: כִּכְתוּבָה בִּשְׁטָר דָּמְיָא, וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן אֶלְעָזָר סָבַר: לָאו כִּכְתוּבָה בִּשְׁטָר דָּמְיָא.

Rabba said: Actually, everyone agrees that one who is owed money from a loan by oral agreement cannot collect from the heirs; and here the tanna’im disagree with regard to whether a loan that is written in the Torah, e.g., one’s obligation to pay if he causes damage, is considered as though it is written in a document. The first tanna holds that a loan that is written in the Torah is considered as though it is written in a document, and may be collected from the heirs. And Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar holds that it is not considered as though it is written in a document, and therefore it may not be collected.

מֵיתִיבִי: הַחוֹפֵר בּוֹר בִּרְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים, וְנָפַל עָלָיו שׁוֹר וַהֲרָגוֹ — פָּטוּר, וְלֹא עוֹד, אֶלָּא שֶׁאִם מֵת הַשּׁוֹר — יוֹרְשֵׁי בַּעַל הַבּוֹר חַיָּיבִין לְשַׁלֵּם דְּמֵי שׁוֹר לִבְעָלָיו!

The Gemara raises an objection against the opinion that one cannot collect a loan that is written in the Torah from the heirs, from a baraita (Tosefta, Bava Kamma 6:2): If one was digging a pit in the public thoroughfare, and an ox fell on the digger of the pit and killed him, the owner of the ox is exempt from paying damages, as the digger of the pit should not have dug the pit. Moreover, if the ox died as a result of the fall, the heirs of the owner of the pit are liable to pay the value of the ox to its owner. This shows that an obligation that is written in the Torah, such as compensation for damage, is collected from heirs.

אָמַר רַבִּי אִילָא אָמַר רַב: כְּשֶׁעָמַד בַּדִּין, וְהָא ״הֲרָגוֹ״ קָתָנֵי! אָמַר רַב אַדָּא בַּר אַהֲבָה: כְּשֶׁעֲשָׂאוֹ טְרֵיפָה.

Rabbi Ila said that Rav said: The baraita is dealing with a case where the digger of the pit stood trial for the damage before he died, and once judgment is rendered by a court the resulting financial obligation is comparable to a written loan, not one that is written in the Torah. The Gemara raises an objection: But it is taught in the baraita that the ox killed him. Rav Adda bar Ahava said: The baraita does not mean that the ox literally killed him, rather, that it rendered him as one who has a wound that will cause him to die within twelve months [tereifa], and there was enough time before his death to sentence him to pay damages.

וְהָאָמַר רַב נַחְמָן, תָּנֵי חַגָּא: מֵת וּקְבָרוֹ! וְהִילְכְתָא דְּיָיתְבִי דַּיָּינֵי אַפּוּמָּא דְבֵירָא.

The Gemara raises an objection: But doesn’t Rav Naḥman say that Ḥagga teaches a slightly different version of the baraita, that if the digger of the pit died from the impact of the ox, and the ox effectively buried him in the ground at the bottom of the pit, his heirs have to pay damages to the owner of the ox? In this scenario, how could it be possible for the digger to stand trial? The Gemara answers: The halakha in the baraita, that the owner of the ox collects from the heirs of the digger, is dealing with a case where judges sat at the opening of the pit and rendered the digger liable to pay damages before he died.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: הַיּוֹצֵא לֵיהָרֵג — מַזִּין עָלָיו מִדַּם חַטָּאתוֹ וּמִדַּם אֲשָׁמוֹ, חָטָא בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה — אֵין נִזְקָקִין לוֹ. מַאי טַעְמָא? אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: מִפְּנֵי שֶׁאֵין מְעַנִּין אֶת דִּינוֹ.

§ The Sages taught another baraita on the same topic: With regard to one taken to be executed, they sprinkle for his sake on the altar from the blood of his sin offering and from the blood of his guilt offering, which he brought earlier. But if he sinned at that time, obligating him to bring a sin offering or a guilt offering, the court does not attend to his obligation, and his execution is not delayed so that he can sacrifice the offering. The Gemara asks: What is the reason for this? Rav Yosef said: It is because the court may not afflict him by forcing him to wait for his judgment, his execution, until the offering is sacrificed.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: אִי הָכִי, אֲפִילּוּ רֵישָׁא נָמֵי! כְּגוֹן שֶׁהָיָה זִבְחוֹ זָבוּחַ בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה.

Abaye said to Rav Yosef: If so, if the offering is not sacrificed in order to avoid afflicting the sentenced by delaying his execution, then this should apply even in the first clause as well, where he had already brought the offering. Why does the court delay his execution until the blood is sprinkled? Rav Yosef answered: The first clause is referring to a case where his offering was already slaughtered at that time, and all that remained to be done was the sprinkling of the blood. Delaying the execution for such a short time is not a problem.

אֲבָל אֵין זִבְחוֹ זָבוּחַ, מַאי? לָא? אַדְּתָנֵי ״חָטָא בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה אֵין נִזְקָקִין לוֹ״, לִיפְלוֹג וְלִיתְנֵי בְּדִידַהּ: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — שֶׁהָיָה זֶבַח זָבוּחַ בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה, אֲבָל אֵין זֶבַח זָבוּחַ — לֹא!

The Gemara asks: But then in a case where he set aside his offering but it was not yet slaughtered, what is the halakha? Is it true that they do not delay his execution in order to sacrifice the offering? If so, instead of teaching a new case and stating: But if he sinned at that time and thereby became obligated to sacrifice a sin offering or a guilt offering, the court does not attend to his obligation, let the baraita distinguish and teach a distinction within the case of where he already brought the offering itself: In what case is this statement, that the blood is sprinkled, said? When his offering was already slaughtered at that time. But if his offering was not yet slaughtered, his execution is not delayed.

הָכִי נָמֵי קָאָמַר: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים — שֶׁהָיָה זֶבַח זָבוּחַ בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה, אֲבָל אֵין זֶבַח זָבוּחַ — נַעֲשָׂה כְּמִי שֶׁחָטָא בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה, וְאֵין נִזְקָקִין לוֹ.

The Gemara answers: That is indeed what he is saying: In what case is this statement said? When his offering was already slaughtered at that time. But if his offering was not yet slaughtered, it is considered as though he sinned at that time, and therefore the court does not attend to his obligation.

מַתְנִי׳ הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁיָּצְאָה לֵיהָרֵג, אֵין מַמְתִּינִין לָהּ עַד שֶׁתֵּלֵד. הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁיָּשְׁבָה עַל הַמַּשְׁבֵּר, מַמְתִּינִין לָהּ עַד שֶׁתֵּלֵד. הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁנֶּהֶרְגָה, נֶהֱנִין בִּשְׂעָרָהּ. בְּהֵמָה שֶׁנֶּהֶרְגָה, אֲסוּרָה בַּהֲנָאָה.

MISHNA: In the case of a pregnant woman who is taken by the court to be executed, the court does not wait to execute her until she gives birth. Rather, she is killed immediately. But with regard to a woman taken to be executed who sat on the travailing chair [hamashber] in the throes of labor, the court waits to execute her until she gives birth. In the case of a woman who was killed through court-imposed capital punishment, one may derive benefit from her hair. But in the case of an animal that was killed through court-imposed execution, e.g., for goring a person, deriving benefit from the animal is prohibited.

גְּמָ׳ פְּשִׁיטָא, גּוּפַהּ הִיא! אִיצְטְרִיךְ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא: הוֹאִיל וּכְתִיב ״כַּאֲשֶׁר יָשִׁית עָלָיו בַּעַל הָאִשָּׁה״, מָמוֹנָא דְבַעַל הוּא, וְלָא לַיפְסְדֵיהּ מִינֵּיהּ, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

GEMARA: Isn’t it obvious that the court executes the pregnant woman rather than waiting? After all, it is part of her body. The Gemara answers: It was necessary for the mishna to teach this, as it might enter your mind to say that since it is written: “And if men strive together, and hurt a woman with child, so that her offspring depart…he shall be fined, as the woman’s husband shall place upon him” (Exodus 21:22), the fetus is considered to be the property of the husband. If so, the court should wait until she gives birth before executing her, and not cause him to lose the fetus. Consequently, the mishna teaches us that the court does not take this factor into account.

וְאֵימָא הָכִי נָמֵי! אָמַר רַבִּי אֲבָהוּ אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אָמַר קְרָא ״וּמֵתוּ גַּם שְׁנֵיהֶם״ — לְרַבּוֹת אֶת הַוָּולָד.

The Gemara asks: But why not say that indeed the court should delay her execution until she gives birth? Rabbi Abbahu says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says: The verse states: “If a man be found lying with a woman married to a husband, then they shall also both of them die, the man that lay with the woman, and the woman” (Deuteronomy 22:22). The amplifying term “both of them” serves to add her fetus, teaching that it dies together with her.

וְהַאי מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ, עַד שֶׁיְּהוּ שְׁנֵיהֶן שָׁוִין, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה! כִּי קָאָמְרִינַן מִ״גַּם״.

The Gemara asks: But this phrase is required for the following halakha: Neither of the two adulterers mentioned in the verse is punished until both of them are equal, i.e., they have both reached majority. This is the statement of Rabbi Yoshiya. The Gemara answers: When you say that the child also dies, it is derived from the word “also,” whereas the halakha that they must be equal is learned from the term “both of them.”

יָשְׁבָה עַל הַמַּשְׁבֵּר וְכוּ׳. מַאי טַעְמָא? כֵּיוָן דְּעָקַר, גּוּפָא אַחֲרִינָא הוּא.

§ The mishna teaches: With regard to a woman taken to be executed who sat on the travailing chair in the throes of labor, the court waits to execute her until she gives birth. The Gemara asks: What is the reason for delaying the execution in this case? The Gemara answers: Once the fetus uproots from its place and begins to leave the woman’s body, it is considered an independent body and may not be killed together with the mother.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הָאִשָּׁה הַיּוֹצְאָה לֵיהָרֵג, מַכִּין אוֹתָהּ כְּנֶגֶד בֵּית הֵרָיוֹן, כְּדֵי שֶׁיָּמוּת הַוָּולָד תְּחִילָּה, כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא תָּבֹא לִידֵי נִיוּוּל. לְמֵימְרָא דְּהִיא קָדְמָה וּמֵתָה בְּרֵישָׁא? וְהָא קַיְימָא לַן דְּוָולָד מָיֵית בְּרֵישָׁא!

Rav Yehuda says that Shmuel says: In the case of a pregnant woman who is taken by the court to be executed, one strikes her opposite the womb, i.e., on the abdomen, so that the fetus dies first and so that she not suffer disgrace as a result of publicly bleeding from labor. The Gemara asks: Is this to say that according to Shmuel if a pregnant woman dies, she dies first, before the fetus? It is clear that this is Shmuel’s assumption, as he mandates killing the fetus before the mother, lest the live fetus bring about the onset of labor as a reaction to the woman’s death. Were the fetus to perish first, before the woman, there would be no need for this. But this is difficult, as we maintain that the fetus dies first.

דִּתְנַן: תִּינוֹק בֶּן יוֹמוֹ נוֹחֵל וּמַנְחִיל, וְאָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: נוֹחֵל בְּנִכְסֵי הָאֵם לְהַנְחִיל לָאַחִין מִן הָאָב.

As we learned in a mishna (Nidda 43b–44a): A baby boy, one day old, inherits the estate of his relatives who died on the day of his birth, and if he dies, he bequeaths that inheritance to his relatives. And Rav Sheshet says: This mishna is teaching that a day-old child inherits his mother’s property when she died after he was born, to bequeath it to his heirs who are not the mother’s heirs, e.g., to his paternal brothers.

דַּוְוקָא בֶּן יוֹם אֶחָד, אֲבָל עוּבָּר — לָא, דְּהוּא מָיֵית בְּרֵישָׁא, וְאֵין הַבֵּן יוֹרֵשׁ אֶת אִמּוֹ בְּקֶבֶר לְהַנְחִיל לָאַחִין מִן הָאָב!

The Gemara explains the difficulty: It is specifically in a case where the boy is one day old that he inherits and bequeaths, but a fetus who died while still in the womb does not inherit and bequeath. The reason is that we presume that the fetus died first, before its mother, and a son does not inherit through his mother while in the grave, in order to bequeath her property to his paternal brothers.

הָנֵי מִילֵּי לְגַבֵּי מִיתָה, אַיְּידֵי דְּוָולָד זוּטְרָא חַיּוּתֵיהּ, עָיְילָא טִיפָּה דְּמַלְאַךְ הַמָּוֶת וּמְחַתֵּךְ לְהוּ לְסִימָנִין, אֲבָל נֶהֶרְגָה — הִיא מֵתָה בְּרֵישָׁא.

The Gemara answers: This matter, i.e., the presumption that the fetus dies first, applies only in a case of natural death. In such a situation, since the fetus’s vitality is minimal, the Angel of Death’s drop of poison enters his body and cuts the two organs that must be severed in ritual slaughter, i.e., the windpipe and the gullet [simanim], thereby killing him before his mother. But in a case where the mother was killed, e.g., if she was executed, she dies first.

וְהָא הֲוָה עוֹבָדָא, וּפַרְכֵּיס עַד תְּלָת פִּרְכּוּסֵי! מִידֵּי דְּהָוֵי אַזְּנַב הַלְּטָאָה דִּמְפַרְכֶּסֶת.

The Gemara asks: Is it true that the fetus always dies first when the mother dies naturally? But there was an incident where the mother died naturally and the fetus made three spasmodic motions afterward. The Gemara answers: That is just as it is with the tail of the lizard, which jerks after being severed from the lizard; it is just a spasmodic motion, which does not indicate that it is still alive.

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁיָּשְׁבָה עַל הַמַּשְׁבֵּר וּמֵתָה בְּשַׁבָּת, מְבִיאִין סַכִּין וּמְקָרְעִים אֶת כְּרֵיסָהּ, וּמוֹצִיאִין אֶת הַוָּולָד. פְּשִׁיטָא, מַאי עָבֵיד?

§ Rav Naḥman says that Shmuel says: In the case of a woman who sat on the travailing chair in the throes of labor, and died on Shabbat, one brings a knife, and tears open her abdomen, and removes the fetus, as it might still be alive, and it could be possible to save its life. The Gemara asks: But isn’t it obvious that this is permitted? After all, what is the person who cuts her abdomen doing?

מְחַתֵּךְ בְּבָשָׂר הוּא! אָמַר רַבָּה: לֹא נִצְרְכָה לְהָבִיא סַכִּין דֶּרֶךְ רְשׁוּת הָרַבִּים.

It is merely cutting flesh, and there is no reason why it should be prohibited. Rabba said: No, the halakha concerning cutting open her abdomen is necessary only to teach that it is permitted to bring a knife by way of the public thoroughfare for that purpose, despite the fact that this constitutes a prohibited labor by Torah law.

וּמַאי קָמַשְׁמַע לַן, דְּמִסְּפֵיקָא מְחַלְּלִינַן שַׁבְּתָא? תְּנֵינָא: מִי שֶׁנָּפְלָה עָלָיו מַפּוֹלֶת, סָפֵק הוּא שָׁם, סָפֵק אֵינוֹ שָׁם, סָפֵק חַי, סָפֵק מֵת, סָפֵק נׇכְרִי, סָפֵק יִשְׂרָאֵל — מְפַקְּחִין עָלָיו אֶת הַגַּל!

The Gemara asks: And what does this teach us? Does it teach that even in a case of uncertainty we desecrate Shabbat for the chance of saving a life? But we already learned this in a mishna (Yoma 83a): With regard to one upon whom a rockslide fell, and there is uncertainty as to whether he is there under the debris or whether he is not there, and there is also uncertainty as to whether he is still alive or whether he is dead, and finally there is uncertainty as to whether the person under the debris is a gentile or a Jew, one clears the pile from atop him on Shabbat.

מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: הָתָם הוּא דַּהֲוָה לֵיהּ חֲזָקָה דְּחַיּוּתָא, אֲבָל הָכָא דְּלָא הֲוָה לֵיהּ חֲזָקָה דְּחַיּוּתָא מֵעִיקָּרָא — אֵימָא לָא, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara answers: It is necessary to teach that one may bring a knife in the case of a woman, lest you say that it is specifically there that one may desecrate Shabbat, as the person who was buried under the rockslide had a presumptive status of being alive and therefore he is assumed to still be alive. But here, where the child had no prior presumptive status of being alive, as he was not yet born, you might say that one may not desecrate Shabbat in order to save his life. Therefore, it is necessary for Shmuel to teach us that even here one may desecrate Shabbat for the possibility of saving the fetus’s life.

הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁנֶּהֶרְגָה וְכוּ׳. וְאַמַּאי? אִיסּוּרֵי הֲנָאָה נִינְהוּ! אָמַר רַב: בְּאוֹמֶרֶת ״תְּנוּ שְׂעָרִי לְבִתִּי״. אִילּוּ אָמְרָה ״תְּנוּ יָדִי לְבִתִּי״, מִי יָהֲבִינַן לַהּ?!

§ The mishna taught: In the case of a woman who was killed through court-imposed capital punishment, one may derive benefit from her hair. The Gemara asks: But why is it permitted? After all, a corpse and its hair are items from which deriving benefit is prohibited. Rav said that this is referring to a case where she says before she dies: Give my hair to my daughter. The Gemara asks: Is the prohibition contingent on the deceased’s wishes? Were she to say: Give my hand to my daughter, would we give the hand to her?

אָמַר רַב: בְּפֵאָה נׇכְרִית, טַעְמָא דְּאָמְרָה ״תְּנוּ״, הָא לֹא אָמְרָה ״תְּנוּ״ — גּוּפַהּ הוּא וּמִיתְּסַר.

Rather, Rav said: This is not referring to the actual hair of the deceased, but to a wig [pe’a nokhrit], which is not part of the deceased’s body. The Gemara infers from Rav’s statement that the reason it is permitted is that she said to give her wig to her daughter, thereby indicating that she did not consider it part of her body. But if she did not say to give her wig to her daughter, it is considered part of her body, and it is forbidden to derive benefit from it.

וְהָא מִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ לְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא, דְּבָעֵי רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא: שְׂעַר נָשִׁים צִדְקָנִיּוֹת מַהוּ?

The Gemara explains why this implication is problematic: But didn’t Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, raise this as a dilemma? As Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina raised a dilemma: With regard to the hair of righteous women in a city whose residents were incited to idolatry and, therefore, all of their property must be burned, what is the halakha? Is it considered their property and burned, or part of their body and not burned?

וְאָמַר רָבָא: בְּפֵאָה נׇכְרִית לָא קָמִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ, כִּי קָמִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ לְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בְּרַבִּי חֲנִינָא דִּתְלֵי בְּסִיכְּתָא.

And Rava said: Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, was not referring to actual hair, but rather he raised his dilemma with regard to a wig. This is difficult according to the opinion of Rav, as his ruling indicates that a wig should be considered part of a woman’s body unless she stipulated otherwise. The Gemara answers: When Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, raised his dilemma as to whether a wig is considered part of the body, he was referring specifically to a case where the wig was hanging on a peg. The dilemma is whether it is considered part of her clothing, which, like her body, is not burned, or whether it is considered like any other property of hers, since she was not wearing it at the time.

הָכָא דִּמְחַבַּר בַּהּ, טַעְמָא דְּאָמְרָה ״תְּנוּ״, הָא לֹא אָמְרָה ״תְּנוּ״ — גּוּפַהּ הוּא וּמִיתְּסַר.

On the other hand, here Rav is referring to a wig that is actually attached to her. In such a case, one may correctly infer that the reason that it is permitted is that the deceased said to give her wig to her daughter, thereby indicating that she did not consider it part of her body. But if she did not say to give her wig to her daughter, it is considered to be part of her body and is prohibited.

קַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ לְרַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק, וְהָא דּוּמְיָא דִּבְהֵמָה קָתָנֵי, מָה הָתָם גּוּפַיהּ — אַף הָכָא נָמֵי גּוּפַיהּ!

This claim, that the mishna is dealing with a wig rather than natural hair, is difficult for Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak. He explains the difficulty: The mishna teaches the issue of the prohibition of the woman’s hair as being similar to the other prohibition it mentions, that of the animal. Just as there, in the case of the animal, it is referring to deriving benefit from its body, so too here, it must be referring to benefit from her body itself, not from a wig.

אֶלָּא אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן: זוֹ מִיתָתָהּ אוֹסַרְתָּהּ, וְזוֹ גְּמַר דִּינָה אוֹסַרְתָּהּ.

Rather, Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak says: The mishna is referring to natural hair, and there is a distinction between the hair of an animal and that of a woman. In the case of this woman, it is her death that causes her to be forbidden. Therefore, the hair, which does not undergo any change when she dies, remains permitted. But in the case of that animal, the verdict causes it to be forbidden, even before it is killed. It is prohibited to derive benefit from the animal as soon as the verdict is issued. Therefore, the hair that is attached to the animal is forbidden as well.

תָּנֵי לֵוִי כְּוָותֵיהּ דְּרַב, תָּנֵי לֵוִי כְּוָותֵיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק. תָּנֵי לֵוִי כְּוָותֵיהּ דְּרַב: הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁיּוֹצְאָה לֵיהָרֵג וְאָמְרָה: ״תְּנוּ שְׂעָרִי לְבִתִּי״ — נוֹתְנִין, מֵתָה — אֵין נוֹתְנִין, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהַמֵּת אָסוּר בַּהֲנָאָה.

Levi teaches a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rav, and Levi also teaches a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak. The Gemara elaborates: Levi teaches a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rav: In the case of a woman who was being taken to be killed and who said: Give my hair to my daughter, one gives it to the daughter. If she died without instructing that it be given to her daughter, one does not give it to the daughter, because it is forbidden to derive benefit from a corpse.

פְּשִׁיטָא! אֶלָּא שֶׁנּוֹיֵי הַמֵּת אָסוּר בַּהֲנָאָה.

The Gemara asks: Isn’t it obvious that this is the reason her hair is prohibited? The Gemara explains that this is referring not to the hair itself, but rather to a wig, and the baraita is teaching that it is forbidden to derive benefit even from the adornments of the deceased, such as a wig.

תַּנְיָא כְּוָותֵיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק: הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁמֵּתָה — נֶהֱנִין בִּשְׂעָרָהּ, בְּהֵמָה שֶׁנֶּהֶרְגָה — אֲסוּרָה בַּהֲנָאָה; וּמָה הֶפְרֵשׁ בֵּין זֶה לָזֶה? זוֹ — מִיתָתָהּ אוֹסַרְתָּהּ, וְזוֹ — גָּמַר דִּינָה אוֹסַרְתָּהּ.

The Gemara further explains: It is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak, as follows: Whereas in the case of a woman who died, one may derive benefit from her hair, with regard to an animal that was put to death, it is forbidden to derive benefit from it. And what is the difference between this case and that one? In this case it is her death that causes her to be forbidden, but in that case the verdict causes the animal to be forbidden.

הֲדַרַן עֲלָךְ הַכֹּל מַעֲרִיכִין.

מַתְנִי׳ אֵין נֶעֱרָכִין פָּחוֹת מִסֶּלַע, וְלֹא יָתֵר עַל חֲמִשִּׁים סֶלַע. כֵּיצַד? נָתַן סֶלַע וְהֶעֱשִׁיר — אֵינוֹ נוֹתֵן כְּלוּם, פָּחוֹת מִסֶּלַע וְהֶעֱשִׁיר — נוֹתֵן חֲמִשִּׁים סֶלַע.

MISHNA: One cannot be charged for a valuation less than a sela, nor can one be charged more than fifty sela. How so? If one gave one sela and became wealthy, he is not required to give anything more, as he has fulfilled his obligation. If he gave less than a sela and became wealthy, he is required to give fifty sela, as he has not fulfilled his obligation.

הָיוּ בְּיָדָיו חָמֵשׁ סְלָעִים, רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: אֵינוֹ נוֹתֵן אֶלָּא אַחַת, וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: נוֹתֵן אֶת כּוּלָּן. אֵין נֶעֱרָכִין פָּחוֹת מִסֶּלַע, וְלֹא יָתֵר עַל חֲמִשִּׁים סֶלַע.

If there were five sela in the possession of the destitute person, and the valuation he undertook is more than five sela, how much should he pay? Rabbi Meir says: He gives only one sela and thereby fulfills his obligation. And the Rabbis say: He gives all five. One cannot be charged for a valuation less than a sela; nor can one be charged more than fifty sela.

גּמ׳ אֵין נֶעֱרָכִין פָּחוֹת מִסֶּלַע. מְנָלַן? דִּכְתִיב: ״וְכׇל עֶרְכְּךָ יִהְיֶה בְּשֶׁקֶל הַקֹּדֶשׁ״, כׇּל עֲרָכִין שֶׁאַתָּה מַעֲרִיךְ לֹא יְהוּ פְּחוּתִין מִשְׁקָל.

GEMARA: The mishna teaches: One cannot be charged for a valuation less than a sela. The Gemara asks: From where do we derive this principle? The Gemara answers: As it is written: “And all your valuations shall be according to the shekel of the Sanctuary” (Leviticus 27:25). This verse indicates that all valuations that you valuate shall not be less than a shekel, which is the equivalent of a sela. One does not fulfill his obligation by giving less than this amount.

וְלֹא יָתֵר עַל חֲמִשִּׁים סְלָעִים. דִּכְתִיב: ״חֲמִשִּׁים״.

The mishna further teaches: Nor can one be charged more than fifty sela. This is the highest valuation specified in the Torah, as it is written: “Then your valuation shall be for the male from twenty years old unto sixty years old, your valuation shall be fifty shekels of silver” (Leviticus 27:3).

הָיוּ בְּיָדָיו חֲמִשָּׁה כּוּ׳. מַאי טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי מֵאִיר? כְּתִיב ״חֲמִשִּׁים״ וּכְתִיב ״שֶׁקֶל״, אוֹ חֲמִשִּׁים אוֹ שֶׁקֶל.

§ The mishna teaches that if there were five sela in the possession of the destitute person, Rabbi Meir says: He gives only one sela and thereby fulfills his obligation, and the Rabbis say: He gives all five. The Gemara asks: What is the reason for the opinion of Rabbi Meir? The Gemara answers: It is written with regard to a male between the ages of twenty and sixty: “Your valuation shall be fifty shekels of silver” (Leviticus 27:3), and the verses likewise specify the valuations for other individuals. And it is also written: “Your valuations shall be according to the shekel of the Sanctuary” (Leviticus 27:25). This teaches that the valuation is either fifty shekels for one who vows to donate the valuation of a man between twenty and sixty, or one shekel, if he cannot afford to pay fifty.

וְרַבָּנַן? הַהוּא, לְכׇל עֲרָכִין שֶׁאַתָּה מַעֲרִיךְ לֹא יְהוּ פְּחוּתִים מִשְׁקָל הוּא דַּאֲתָא, הֵיכָא דְּאִית לֵיהּ — אָמַר קְרָא: ״אֲשֶׁר תַּשִּׂיג יַד הַנּוֹדֵר״, וַהֲרֵי יָדוֹ מַשֶּׂגֶת.

And how do the Rabbis respond to this reasoning? According to the Rabbis, that second verse comes to teach that all valuations that you valuate shall not be less than a shekel, but in a case where the individual has more than a shekel, the verse states: “According to the means of him that vowed shall the priest value him” (Leviticus 27:8), and as he has the means to pay more than a shekel, he is required to pay the maximum that he can afford.

וְרַבִּי מֵאִיר? הָהוּא ״יַד הַנּוֹדֵר וְלֹא יַד הַנִּידָּר״ הוּא דַּאֲתָא, וְרַבָּנַן, לָאו מִמֵּילָא שָׁמְעַתְּ מִינַּהּ דְּהֵיכָא דְּיָדוֹ מַשֶּׂגֶת שְׁקוֹל מִינֵּיהּ?

And how does Rabbi Meir respond to this reasoning? According to Rabbi Meir, that verse comes to teach that the charge is calculated according to the means of one who took the vow and not according to the means of the one about whom the vow was made. Consequently, if a poor man vowed to donate the valuation of a rich man, the amount to be paid is calculated according to what the poor man, not the rich man, can afford. And how do the Rabbis respond to this reasoning? They would say: Doesn’t it emerge by itself that you also learn from this verse that in a case where he has the means to pay more than a shekel, you should take from him the maximum that he can afford?

אָמַר רַב אַדָּא בַּר אַהֲבָה: הָיוּ בְּיָדָיו חָמֵשׁ סְלָעִים, וְאָמַר ״עֶרְכִּי עָלַי״, וְחָזַר וְאָמַר ״עֶרְכִּי עָלַי״, וְנָתַן אַרְבַּע לַשְּׁנִיָּה וְאֶחָד לָרִאשׁוֹנָה — יָצָא יְדֵי שְׁתֵּיהֶן.

§ The Gemara cites a ruling based upon the opinion of the Rabbis. Rav Adda bar Ahava says: If one had five sela in his possession and said: It is incumbent upon me to donate my valuation, and he then said again: It is incumbent upon me to donate my valuation, and he gave four sela for the second vow and one sela for the first vow, he has fulfilled his obligation to pay for both of the vows. Consequently, even if he becomes wealthy, he is not required to make any further payments.

מַאי טַעְמָא? בַּעַל חוֹב מְאוּחָר שֶׁקָּדַם וְגָבָה — מַה שֶּׁגָּבָה גָּבָה.

What is the reason for this? There is a principle that with regard to a creditor holding a promissory note dated later than the notes of other creditors, who collected his debt before the other creditors collected theirs, whatever he has collected he has collected, and it is not expropriated from him even if the debtor does not have the means to pay back all his creditors.

בְּעִידָּנָא דְּיָהֵיב לַשְּׁנִיָּה, מְשַׁעְבַּד לְרִאשׁוֹנָה. בְּעִידָּנָא דְּיָהֵיב לָרִאשׁוֹנָה, תּוּ לֵית לֵיהּ.

In this case, since at the time that he gave the four sela for the second vow, his possessions were liened for the payment of his first vow, it is as though he had no possessions at all with which to pay the second vow, and he therefore fulfilled the second vow even though he paid less than the full amount of money in his possession. Then, at the time he gave one sela for payment of the first vow, he in fact had no more than one sela, as he had given the other four sela in payment of the second vow, and therefore he fulfills his obligation by paying one sela.