Why was it necessary for the verses in the Torah to specify that an animal is killed even if it killed a minor? Is this the case also if it was a shor tam? If an animal kills without intent to kill or with intent to kill an animal and killed a person and other such cases, the animal is not killed, but Rav and Shmuel have a debate about whether or not the ransom needs to be paid. The Gemara brings in the opinion of Rabbi Shimon who holds that even if a person tried to kill someone but killed someone else instead, he is not punished by death. Apparently, the tana of our Mishna does not agree with his approach. Rabbi Yehuda disagrees with Rabbi Shimon. From where in the Torah is each opinion derived? Once an animal is sentenced to death, it is forbidden to benefit from it. Therefore, if one sells it, the sale is invalid and likewise if one dedicates it to the Temple, it is not sacred and if one slaughters it, the meat is forbidden. However, before the sentence, all those acts are valid.

Bava Kamma 44

Share this shiur:

Bava Kamma

Masechet Bava Kamma is sponsored by the Futornick Family in loving memory of their fathers and grandfathers, Phillip Kaufman and David Futornick.

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

Bava Kamma

Masechet Bava Kamma is sponsored by the Futornick Family in loving memory of their fathers and grandfathers, Phillip Kaufman and David Futornick.

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

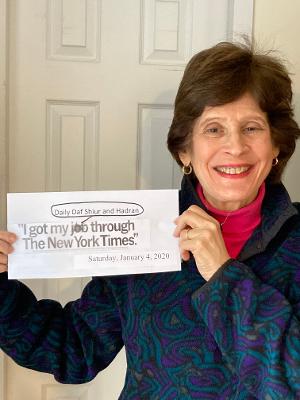

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Bava Kamma 44

שׁוֹר בְּאָדָם – שֶׁעָשָׂה בּוֹ קְטַנִּים כִּגְדוֹלִים, אֵינוֹ דִּין שֶׁחַיָּיב עַל הַקְּטַנִּים כִּגְדוֹלִים?

then in the case of an ox killing a person, where the Torah renders small oxen like large ones with regard to this act, as a young calf that kills a person is killed just as an adult ox that kills a person, is it not logical that the Torah renders it liable for killing minors, i.e., a boy or a girl, just as for killing adults? Why is it necessary for the verse to teach this halakha?

לֹא, אִם אָמַרְתָּ אָדָם בְּאָדָם – שֶׁכֵּן חַיָּיב בְּאַרְבָּעָה דְּבָרִים, תֹּאמַר בְּשׁוֹר – שֶׁאֵינוֹ חַיָּיב בְּאַרְבָּעָה דְּבָרִים? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״אוֹ בֵן יִגָּח אוֹ בַת יִגָּח״ – לְחַיֵּיב עַל הַקְּטַנִּים כִּגְדוֹלִים.

The Gemara rejects this claim: No, this cannot be derived by logic alone. If you say that a person who kills a person is liable even when the victim is a minor, this may be due to the extra severity in the case of a human assailant, as he is liable to pay four types of indemnity for causing injury; pain, humiliation, medical costs, and loss of livelihood, in addition to payment for the actual damage. Shall you also say that this is the halakha with regard to an ox, whose owner is not liable to pay these four types of indemnity? Clearly, this halakha cannot be derived merely through logical comparison between the two cases. Therefore, the verse states: “Whether it has gored a son or has gored a daughter,” to render it liable for minors as well as adults.

וְאֵין לִי אֶלָּא בְּמוּעָדִין, בְּתָם מִנַּיִן?

And I have derived this halakha only with regard to forewarned oxen; from where do I derive that in the case of an innocuous ox, it is killed if it kills a boy or a girl?

דִּין הוּא – הוֹאִיל וְחִיֵּיב בְּאִישׁ וְאִשָּׁה, וְחִיֵּיב בְּבֵן וּבַת; מָה כְּשֶׁחִיֵּיב בְּאִישׁ וְאִשָּׁה – לֹא חִלַּקְתָּ בּוֹ בֵּין תָּם לְמוּעָד; אַף כְּשֶׁחִיֵּיב בְּבֵן וּבַת – לֹא תַּחְלוֹק בּוֹ בֵּין תָּם לְמוּעָד.

The baraita asks: Could this not be derived through logical inference? Since the Torah renders an ox liable to be killed for killing a man or a woman, and likewise renders it liable to be killed for killing a boy or a girl; then just as when it renders it liable to be killed for killing a man or a woman you do not differentiate between an innocuous ox and a forewarned ox, as both are stoned, so too, when it renders an ox liable to be killed for killing a boy or a girl do not differentiate between an innocuous ox and a forewarned ox.

וְעוֹד, קַל וָחוֹמֶר – מָה אִישׁ וְאִשָּׁה, שֶׁכֵּן הוֹרַע כֹּחָם בִּנְזָקִין – לֹא חִלַּקְתָּ בּוֹ בֵּין תָּם לְמוּעָד; בֵּן וּבַת, שֶׁיִּפָּה כֹּחָם בִּנְזָקִין – אֵינוֹ דִּין שֶׁלֹּא תַּחְלוֹק בָּהֶן בֵּין תָּם לְמוּעָד?

And furthermore, it can be inferred a fortiori: If with regard to a man or a woman, whose power is diminished with regard to damages because adults who cause damage are liable to pay, but nevertheless you do not differentiate between an innocuous ox and a forewarned ox that kills them; then with regard to a boy or girl, whose power is enhanced with regard to damages because they are not liable to pay for damage they cause, is it not logical that you should not differentiate between an innocuous ox and a forewarned ox that kills them?

אָמַרְתָּ: וְכִי דָּנִין קַל מֵחָמוּר לְהַחְמִיר עָלָיו? אִם הֶחְמִיר בְּמוּעָד הֶחָמוּר, תַּחְמִיר בְּתָם הַקַּל?

The baraita answers that you could say in response: But does one derive the halakha of a lenient matter from a stringent matter in order to be more stringent with regard to it? If the Torah is stringent with regard to the case of a forewarned ox, which is a stringent matter, rendering it liable to be killed for killing a minor, does that mean that you should be stringent with regard to an innocuous ox, which is a relatively lenient matter?

וְעוֹד: אִם אָמַרְתָּ בְּאִישׁ וְאִשָּׁה – שֶׁכֵּן חַיָּיבִין בְּמִצְוֹת, תֹּאמַר בְּבֵן וּבַת – שֶׁפְּטוּרִין מִן הַמִּצְוֹת?

And furthermore, there is another reason to reject the earlier opinion: If you say that an innocuous ox is liable to be killed for killing a man or a woman, as they are obligated to observe the mitzvot, which gives them importance, does that mean that you should say the same with regard to a boy or a girl, who are exempt from the mitzvot?

תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״אוֹ בֵן יִגָּח אוֹ בַת יִגָּח״ – נְגִיחָה בְּתָם נְגִיחָה בְּמוּעָד, נְגִיחָה לְמִיתָה נְגִיחָה לִנְזָקִין.

Since this halakha could not have been derived through logic alone, the verse states: “Whether it has gored a son or has gored a daughter,” stating the phrase “has gored” twice, to teach that it is referring both to the goring of an innocuous ox and to the goring of a forewarned ox, and both to goring that causes death and to goring that causes injury. In all these cases the owner of the ox is liable even if the ox gores a minor.

מַתְנִי׳ שׁוֹר שֶׁהָיָה מִתְחַכֵּךְ בַּכּוֹתֶל – וְנָפַל עַל הָאָדָם; נִתְכַּוֵּין לַהֲרוֹג אֶת הַבְּהֵמָה – וְהָרַג אֶת הָאָדָם; לְגוֹי – וְהָרַג בֶּן יִשְׂרָאֵל; לִנְפָלִים – וְהָרַג בֶּן קַיָּימָא; פָּטוּר.

MISHNA: If an ox was rubbing against a wall, and as a result the wall fell on a person and killed him; or if the ox intended to kill another animal but killed a person; or if it intended to kill a gentile but killed a Jew; or intended to kill a non-viable baby but killed a viable person; in all these cases the ox is exempt from being killed.

גְּמָ׳ אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: פָּטוּר מִמִּיתָה, וְחַיָּיב בְּכוֹפֶר. וְרַב אָמַר: פָּטוּר מִזֶּה וּמִזֶּה.

GEMARA: Shmuel says: The ox is exempt from being put to death, since it did not intend to kill, but its owner is liable to pay ransom. And Rav says: They are exempt from this liability and from that liability.

וְאַמַּאי? הָא תָּם הוּא! כִּדְאָמַר רַב: בְּמוּעָד לִיפּוֹל עַל בְּנֵי אָדָם בְּבוֹרוֹת, הָכָא נָמֵי – בְּמוּעָד לְהִתְחַכֵּךְ עַל בְּנֵי אָדָם בִּכְתָלִים.

The Gemara asks about Shmuel’s opinion: And why is he liable to pay ransom? Isn’t the ox innocuous with regard to this action? The Gemara answers: As Rav says in a different context, it is referring to an ox that was forewarned with regard to falling on people in pits. Here too, it is referring to an ox that was forewarned with regard to rubbing against walls, causing them to fall on people.

אִי הָכִי, בַּר קְטָלָא הוּא! בִּשְׁלָמָא הָתָם – דַּחֲזָא יְרוֹקָא וּנְפַל, אֶלָּא הָכָא – מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר?

The Gemara asks: If so, if it was forewarned with regard to this behavior, it clearly intended to kill the person and is therefore subject to being put to death, contrary to the ruling in the mishna. The Gemara explains: Granted there, in the case where the ox was forewarned with regard to falling on people in pits, it could be that it saw a vegetable on the edge of the pit and subsequently fell in, without any intention to kill. But here, where it rubbed against a wall, causing it to fall on a person, and was forewarned with regard to this behavior, what is there to say in its defense?

הָכָא נָמֵי – בְּמִתְחַכֵּךְ בַּכּוֹתֶל לַהֲנָאָתוֹ. וּמְנָא יָדְעִינַן? דְּבָתַר דִּנְפַל קָא מִתְחַכַּךְ בֵּיהּ.

The Gemara answers: Here also the case is where it rubbed against the wall for its pleasure and not in order to kill. The Gemara asks: And from where do we know that it did not intend to kill? The Gemara answers: Because even after the wall fell it was still rubbing against it, which proves that this was its intention.

וְאַכַּתִּי צְרוֹרוֹת נִינְהוּ! אָמַר רַב מָרִי בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב כָּהֲנָא: דְּקָאָזֵיל מִינֵּיהּ מִינֵּיהּ.

The Gemara asks: But still, is it not a case of pebbles? Is this case not analogous to damage caused by pebbles inadvertently propelled from under the feet of an animal while it is walking, which is not considered damage caused directly by the ox, but rather, damage caused indirectly? Ransom is not imposed for such indirect killing. Rav Mari, son of Rav Kahana, said: It is a case where the wall gradually gave way under the pressure applied by the ox, and so while the ox was still pushing the wall it collapsed and killed the person.

תַּנְיָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל – וּתְיוּבְתָּא דְּרַב: יֵשׁ חַיָּיב בְּמִיתָה וּבְכוֹפֶר, וְיֵשׁ חַיָּיב בְּכוֹפֶר וּפָטוּר מִמִּיתָה, וְיֵשׁ חַיָּיב בְּמִיתָה וּפָטוּר מִן הַכּוֹפֶר, וְיֵשׁ פָּטוּר מִזֶּה וּמִזֶּה.

It is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Shmuel, and this baraita is a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Rav: There are cases where the ox is liable to be put to death and the owner is liable to pay ransom, and there are cases where the owner is liable to pay ransom but the ox is exempt from being put to death, and there are cases where the ox is liable to be put to death but the owner is exempt from paying ransom, and there are cases where they are exempt from this punishment and from that one.

הָא כֵּיצַד? מוּעָד בְּכַוָּונָה – חַיָּיב בְּמִיתָה וּבְכוֹפֶר. מוּעָד שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה – חַיָּיב בְּכוֹפֶר וּפָטוּר מִמִּיתָה. תָּם בְּכַוָּונָה – חַיָּיב בְּמִיתָה וּפָטוּר מִכּוֹפֶר. תָּם שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה – פָּטוּר מִזֶּה וּמִזֶּה.

How so? In a case where a forewarned ox kills a person intentionally, the ox is liable to be put to death and the owner is liable to pay ransom; if a forewarned ox kills unintentionally, the owner is liable to pay ransom but the ox is exempt from being put to death; if an innocuous ox kills intentionally, the ox is liable to be put to death but the owner is exempt from paying ransom; and if an innocuous ox kills unintentionally, they are exempt from this punishment and from that one. The baraita states explicitly that although a forewarned ox that kills a person unintentionally is exempt from being put to death, its owner is liable to pay ransom, in accordance with Shmuel’s opinion, and in contrast with Rav’s opinion.

וְהַנְּזָקִין שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה – רַבִּי יְהוּדָה מְחַיֵּיב, וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן פּוֹטֵר.

The baraita adds: And for injuries caused by an ox unintentionally, from which the victim is not killed, Rabbi Yehuda deems the owner liable to pay for the injury and Rabbi Shimon exempts him.

מַאי טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי יְהוּדָה? יָלֵיף מִכּוֹפְרוֹ; מָה כּוֹפְרוֹ – שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה חַיָּיב, אַף הַנְּזָקִין נָמֵי – שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה חַיָּיב.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason for the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda? The Gemara answers: He derives the halakha with regard to injury caused by the ox from the halakha with regard to its owner’s ransom payment. Just as with regard to its owner’s ransom payment he is liable even if the ox gores unintentionally, so too, with regard to injuries he is also liable even if it gores unintentionally.

וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן יָלֵיף מִקְּטָלֵיהּ דְּשׁוֹר, מָה קְטָלֵיהּ – שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה פָּטוּר, אַף נְזָקִין – שֶׁלֹּא בְּכַוָּונָה פָּטוּר.

And Rabbi Shimon derives his opinion from the halakha of the putting to death of an ox by the court: Just as with regard to its being put to death, if it kills a person unintentionally it is exempt, so too, if it causes injuries unintentionally its owner is exempt from payment.

וְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה נָמֵי, נֵילַף מִקְּטָלֵיהּ! דָּנִין תַּשְׁלוּמִין מִתַּשְׁלוּמִין, וְאֵין דָּנִין תַּשְׁלוּמִין מִמִּיתָה.

The Gemara questions the above explanation: And let Rabbi Yehuda also derive the halakha concerning an ox unintentionally causing injury from the halakha of its being put to death. The Gemara answers: In his opinion, we can derive a halakha with regard to payment for injury from the halakha of ransom, which is another halakha with regard to payment. But we cannot derive a halakha with regard to payment from a halakha concerning death.

וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן נָמֵי, נֵילַף מִכּוֹפְרוֹ! דָּנִין חִיּוּבֵיהּ דְּשׁוֹר מֵחִיּוּבֵיהּ דְּשׁוֹר, לְאַפּוֹקֵי כּוֹפֶר דְּחִיּוּבֵיהּ דִּבְעָלִים הוּא.

Conversely, the Gemara asks: And let Rabbi Shimon also derive the halakha here from the halakha concerning its owner’s ransom payment. The Gemara answers: We can derive a halakha with regard to the liability of an ox from a halakha with regard to the liability of an ox, to the exclusion of the payment of ransom, which is the liability of the owner. Compensation for injury is considered the ox’s liability, as it is the ox that caused the injury, whereas the ransom paid is for the owner’s atonement. Therefore, the halakha concerning injury cannot be derived from the halakha of ransom, as they are dissimilar.

נִתְכַּוֵּין לַהֲרוֹג אֶת הַבְּהֵמָה וְהָרַג אֶת הָאָדָם [וְכוּ׳] – פָּטוּר. הָא נִתְכַּוֵּין לַהֲרוֹג אֶת זֶה, וְהָרַג אֶת זֶה – חַיָּיב, מַתְנִיתִין דְּלָא כְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן. דְּתַנְיָא, רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: אֲפִילּוּ נִתְכַּוֵּין לַהֲרוֹג אֶת זֶה, וְהָרַג אֶת זֶה – פָּטוּר.

§ The mishna teaches that if an ox intended to kill another animal but killed a person, or if it intended to kill a person for whom it would not be liable to be put to death but killed a person for whom it would be liable, it is exempt. The Gemara infers: If the ox intended to kill this person, for whom it would be liable, but killed that person instead, it is still liable. Accordingly, the mishna is not in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Shimon, as it is taught in a baraita that Rabbi Shimon says: Even if the ox intended to kill this person but killed that person, it is exempt.

מַאי טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן? דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״הַשּׁוֹר יִסָּקֵל וְגַם בְּעָלָיו יוּמָת״ – כְּמִיתַת בְּעָלִים, כָּךְ מִיתַת הַשּׁוֹר; מָה בְּעָלִים – עַד דְּמִיכַּוֵּין לֵיהּ, אַף שׁוֹר נָמֵי – עַד דְּמִיכַּוֵּין לֵיהּ.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason for the opinion of Rabbi Shimon? The Gemara answers that it is because the verse states: “The ox shall be stoned, and its owner also shall be put to death” (Exodus 21:29); the juxtaposition of the ox and its owner indicates that as the death of the owner, i.e., a person, for killing another person, so is the death of the ox for killing a person. In other words, the two halakhot are applied in the same circumstances. Specifically, just as the owner, i.e., a person, is not liable to receive court-imposed capital punishment unless he intends to kill the person whom he ultimately kills, so too, an ox is not put to death either, unless it intends to kill the one whom it ultimately kills.

וּבְעָלִים גּוּפַיְיהוּ מְנָלַן? דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״וְאָרַב לוֹ וְקָם עָלָיו״ – עַד שֶׁיִּתְכַּוֵּין לוֹ.

The Gemara asks: And with regard to the owner himself, from where do we derive that he is not liable unless he killed the one whom he intended to kill? It is as the verse states: “And he lay in wait for him, and rose against him, and struck him mortally and he died” (Deuteronomy 19:11). From the term “for him,” Rabbi Shimon derives that the killer is not liable unless he intends to kill him, i.e., the one whom he ultimately killed.

וְרַבָּנַן, הַאי ״וְאָרַב לוֹ״ מַאי עָבְדִי לֵיהּ? אָמְרִי דְּבֵי רַבִּי יַנַּאי: פְּרָט לַזּוֹרֵק אֶבֶן לְגוֹ.

The Gemara asks: And what do the Rabbis, who deem the killer liable in that case and who therefore disagree with Rabbi Shimon’s opinion, do with this phrase: “And he lay in wait for him”? How do they interpret it? The Gemara answers that the Sages of the school of Rabbi Yannai say that this phrase excludes from liability one who throws a stone into an area where there are several people, some of whom are people for whom he would not be liable to receive court-imposed capital punishment, e.g., gentiles, and a stone killed a person for whom he would receive court-imposed capital punishment.

הֵיכִי דָמֵי? אִילֵּימָא דְּאִיכָּא תִּשְׁעָה גּוֹיִם וְאֶחָד יִשְׂרָאֵל בֵּינֵיהֶם – תִּיפּוֹק לֵיהּ דְּרוּבָּא גּוֹיִם נִינְהוּ; אִי נָמֵי פַּלְגָא וּפַלְגָא – סְפֵק נְפָשׁוֹת לְהָקֵל!

The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of this case? If we say that there are nine gentiles in the crowd and one Jew among them, even without the verse derive the exemption from the fact that a majority of them are gentiles. Alternatively, even if half the people are gentiles and half are Jews, derive the exemption from the principle that when there is uncertainty concerning capital law, the halakha is to be lenient.

לָא צְרִיכָא, דְּאִיכָּא תִּשְׁעָה יִשְׂרְאֵלִים וְאֶחָד גּוֹי. דְּאַף עַל גַּב דְּרוּבָּא יִשְׂרְאֵלִים נִינְהוּ; כֵּיוָן דְּאִיכָּא חֲדא גּוֹי בֵּינַיְיהוּ – הָוֵי לֵיהּ קָבוּעַ, וְכׇל קָבוּעַ כְּמֶחֱצָה עַל מֶחֱצָה דָּמֵי, וְסָפֵק נְפָשׁוֹת לְהָקֵל.

The Gemara answers: No, the verse is necessary in a case where there are nine Jews and one gentile. Although a majority of them are Jews, the thrower is exempt from liability because there is one gentile among them who is considered fixed in his place, and the legal status of any item fixed in its place is like that of an uncertainty that is equally balanced; and when there is uncertainty concerning capital law the halakha is to be lenient. This is what the Rabbis derive from the phrase: “And he lay in wait for him.”

מַתְנִי׳ שׁוֹר הָאִשָּׁה, וְשׁוֹר הַיְּתוֹמִים, שׁוֹר הָאַפּוֹטְרוֹפּוֹס, שׁוֹר הַמִּדְבָּר, שׁוֹר הַהֶקְדֵּשׁ, שׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת וְאֵין לוֹ יוֹרְשִׁין – הֲרֵי אֵלּוּ חַיָּיבִין מִיתָה. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: שׁוֹר הַמִּדְבָּר, שׁוֹר הַהֶקְדֵּשׁ, שׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת – פְּטוּרִין מִן הַמִּיתָה, לְפִי שֶׁאֵין לָהֶם בְּעָלִים.

MISHNA: With regard to an ox belonging to a woman, and similarly an ox belonging to orphans, and an ox belonging to orphans that is in the custody of their steward, and a desert ox, which is ownerless, and an ox that was consecrated to the Temple treasury, and an ox belonging to a convert who died and has no heirs, rendering the ox ownerless; all of these oxen are liable to be put to death for killing a person. Rabbi Yehuda says: A desert ox, a consecrated ox, and an ox belonging to a convert who died are exempt from being put to death, since they have no owners.

גְּמָ׳ תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״שׁוֹר״ ״שׁוֹר״ שִׁבְעָה – לְהָבִיא שׁוֹר הָאִשָּׁה, שׁוֹר הַיְּתוֹמִים, שׁוֹר הָאַפּוֹטְרוֹפּוֹס, שׁוֹר הַמִּדְבָּר, שׁוֹר הַהֶקְדֵּשׁ, שׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת וְאֵין לוֹ יוֹרְשִׁין. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: שׁוֹר הַמִּדְבָּר, שׁוֹר הַהֶקְדֵּשׁ, שׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת וְאֵין לוֹ יוֹרְשִׁין – פְּטוּרִין מִן הַמִּיתָה, לְפִי שֶׁאֵין לָהֶם בְּעָלִים.

GEMARA: The Sages taught: In the passage discussing an ox that kills a person (Exodus 21:28–32), the Torah states: “An ox,” “an ox,” repeating this word seven times, to include an additional six cases, in addition to the classic case of an ox goring and killing a person. They are: An ox belonging to a woman, an ox belonging to orphans, an ox belonging to orphans that is in the custody of a steward, a desert ox, a consecrated ox, and an ox belonging to a convert who died and has no heirs. Rabbi Yehuda says: A desert ox, a consecrated ox, and an ox belonging to a convert who died and has no heirs are all exempt from being put to death, since they have no owners.

אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: פּוֹטֵר הָיָה רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אֲפִילּוּ נָגַח וּלְבַסּוֹף הִקְדִּישׁ, נָגַח וּלְבַסּוֹף הִפְקִיר.

Rav Huna says: Rabbi Yehuda would deem the ox exempt even if it gored and killed and its owner ultimately consecrated it, or if it gored and he ultimately renounced his ownership over it, since at the time of the trial in court the ox does not have an owner.

מִמַּאי? מִדְּקָתָנֵי תַּרְתֵּי – שׁוֹר הַמִּדְבָּר, וְשׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת וְאֵין לוֹ יוֹרְשִׁין. שׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת מַאי נִיהוּ? דְּכֵיוָן דְּאֵין לוֹ יוֹרְשִׁין – הֲוָה לֵיהּ שׁוֹר הֶפְקֵר; הַיְינוּ שׁוֹר הַמִּדְבָּר, הַיְינוּ שׁוֹר הַגֵּר שֶׁמֵּת וְאֵין לוֹ יוֹרְשִׁין! אֶלָּא לָאו הָא קָמַשְׁמַע לַן – דַּאֲפִילּוּ נָגַח וּלְבַסּוֹף הִקְדִּישׁ, נָגַח וּלְבַסּוֹף הִפְקִיר? שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ.

The Gemara asks: From where did Rav Huna derive this assertion? From the fact that Rabbi Yehuda teaches two cases, a desert ox and an ox belonging to a convert who died and has no heirs. What is the legal status of an ox belonging to a convert who died? Since he has no heirs it is considered to be an ownerless ox. Accordingly, the case of a desert ox is the same as the case of an ox belonging to a convert who died and has no heirs, and it does not seem necessary for the baraita to state both cases. Rather, does it not teach us this: That even if the ox gored and he ultimately consecrated it, or, if it gored and he ultimately renounced ownership over it, it is exempt, just as in a case where a convert’s ox gores and subsequently the owner dies? The Gemara concludes: Indeed, conclude from the baraita that this is the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda.

תַּנְיָא נָמֵי הָכִי, יָתֵר עַל כֵּן אָמַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: אֲפִילּוּ נָגַח וּלְבַסּוֹף הִקְדִּישׁ, נָגַח וּלְבַסּוֹף הִפְקִיר – פָּטוּר, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְהוּעַד בִּבְעָלָיו״ – ״וְהֵמִית וְגוֹ׳״, עַד שֶׁתְּהֵא מִיתָה וְהַעֲמָדָה בַּדִּין שָׁוִין כְּאֶחָד.

This assertion is also taught in a baraita: Moreover, Rabbi Yehuda said that even if it gored and he ultimately consecrated it, or if it gored and he ultimately renounced ownership over it, the ox is exempt, as it is stated: “And warning has been given [vehuad] to its owner…and it killed…the ox shall be stoned” (Exodus 21:29). It is derived from here that the owner of the ox is exempt unless the ox’s status as the owner’s property at the time of the death of the victim and at the time of the owner’s standing trial is the same, i.e., that the ox has an owner.

וּגְמַר דִּין לָא בָּעֵינַן? וְהָא ״הַשּׁוֹר יִסָּקֵל״ גְּמַר דִּין הוּא! אֶלָּא אֵימָא: עַד שֶׁתְּהֵא מִיתָה, וְהַעֲמָדָה בַּדִּין, וּגְמַר דִּין שָׁוִין כְּאֶחָד.

The Gemara asks: But don’t we require that the ox’s status be the same at the time of the verdict as well? And isn’t the phrase “the ox shall be stoned” also referring to the verdict? Rather, emend the statement and say that the owner of the ox is exempt unless the ox’s status as the owner’s property at the time of the death of the victim and at the time of the owner’s standing trial and at the time of the verdict are identical as one.

מַתְנִי׳ שׁוֹר שֶׁהוּא יוֹצֵא לִיסָּקֵל, וְהִקְדִּישׁוֹ בְּעָלָיו – אֵינוֹ מוּקְדָּשׁ. שְׁחָטוֹ – בְּשָׂרוֹ אָסוּר. וְאִם עַד שֶׁלֹּא נִגְמַר דִּינוֹ הִקְדִּישׁוֹ בְּעָלָיו – מוּקְדָּשׁ. וְאִם שְׁחָטוֹ – בְּשָׂרוֹ מוּתָּר.

MISHNA: With regard to an ox that is leaving court to be stoned for killing a person and its owner then consecrated it, it is not considered consecrated, i.e., the consecration does not take effect, since deriving benefit from the ox is prohibited and the ox is therefore worthless. If one slaughtered it, its flesh is forbidden to be eaten and it is prohibited to derive benefit from it. But if its owner consecrated it before its verdict the ox is considered consecrated, and if he slaughtered it its flesh is permitted.

מְסָרוֹ לְשׁוֹמֵר חִנָּם וּלְשׁוֹאֵל לְנוֹשֵׂא שָׂכָר וּלְשׂוֹכֵר – נִכְנְסוּ תַּחַת הַבְּעָלִים; מוּעָד – מְשַׁלֵּם נֶזֶק שָׁלֵם, וְתָם – מְשַׁלֵּם חֲצִי נֶזֶק.

If the owner of an ox conveyed it to an unpaid bailee, or to a borrower, or to a paid bailee, or to a renter, and it caused damage while in their custody, they enter into the responsibilities and liabilities in place of the owner. Therefore, if it was forewarned the bailee pays the full cost of the damage, and if it was innocuous he pays half the cost of the damage.

גְּמָ׳ תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: שׁוֹר שֶׁהֵמִית; עַד שֶׁלֹּא נִגְמַר דִּינוֹ – מְכָרוֹ

GEMARA: The Sages taught: With regard to an ox that killed a person, if its owner sold it before its verdict,