Why does one make a blessing on oil? In what circumstances? The gemara brings various items that are part of trees but aren’t the fruit of the tree and questions what blessing one should make on them? Is something that protects the fruit considered like the fruit itself? if so, is it true even if it’s at the early stage of growth?

Berakhot 36

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

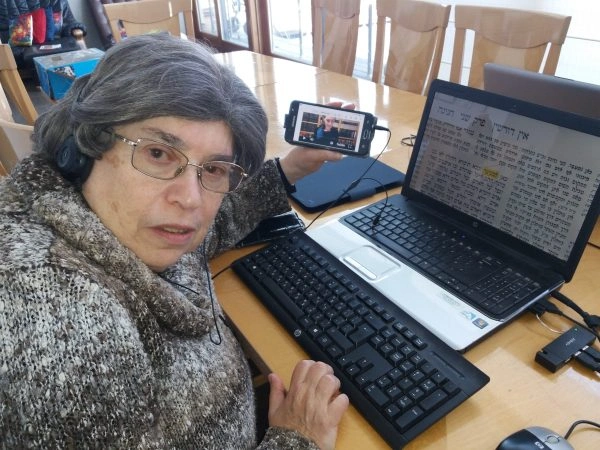

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Berakhot 36

דְּכוּלְּהוּ שִׁלְקֵי.

in which all boiled vegetables were boiled. A certain amount of oil is added to anigeron.

אִם כֵּן, הָוֵה לֵיהּ אֲנִיגְרוֹן עִיקָּר וְשֶׁמֶן טָפֵל, וּתְנַן, זֶה הַכְּלָל: כֹּל שֶׁהוּא עִיקָּר וְעִמּוֹ טְפֵלָה, מְבָרֵךְ עַל הָעִיקָּר וּפוֹטֵר אֶת הַטְּפֵלָה!

However, if so, here too, anigeron is primary and oil is secondary, and we learned in a mishna: This is the principle: Any food that is primary, and it is eaten with food that is secondary, one recites a blessing over the primary food, and that blessing exempts the secondary from the requirement to recite a blessing before eating it. One need recite a blessing only over the anigeron.

הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן — בְּחוֹשֵׁשׁ בִּגְרוֹנוֹ. דְּתַנְיָא: הַחוֹשֵׁשׁ בִּגְרוֹנוֹ לֹא יְעָרְעֶנּוּ בְּשֶׁמֶן תְּחִלָּה בְּשַׁבָּת, אֲבָל נוֹתֵן שֶׁמֶן הַרְבֵּה לְתוֹךְ אֲנִיגְרוֹן וּבוֹלֵעַ.

The Gemara reconciles: With what are we dealing here? With one who has a sore throat, which he is treating with oil. As it was taught in a baraita: One who has a sore throat should not, ab initio, gargle oil on Shabbat for medicinal purposes, as doing so would violate the decree prohibiting the use of medicine on Shabbat. However, he may, even ab initio, add a large amount of oil to the anigeron and swallow it. Since it is common practice to swallow oil either alone or with a secondary ingredient like anigeron for medicinal purposes, in this case one recites: Who creates fruit of the tree.

פְּשִׁיטָא! מַהוּ דְתֵימָא: כֵּיוָן דְּלִרְפוּאָה קָא מְכַוֵּין לָא לְבָרֵיךְ עֲלֵיהּ כְּלָל, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן כֵּיוָן דְּאִית לֵיהּ הֲנָאָה מִינֵּיהּ, בָּעֵי בָּרוֹכֵי.

The Gemara challenges: This is obvious that one must recite a blessing. The Gemara responds: Lest you say: Since he intends to use it for medicinal purposes, let him not recite a blessing over it at all, as one does not recite a blessing before taking medicine. Therefore, it teaches us that, since he derived pleasure from it, he must recite a blessing over it.

קִמְחָא דְחִיטֵּי, רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר: ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״, וְרַב נַחְמָן אָמַר: ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיֶה בִּדְבָרוֹ״.

The Gemara clarifies: If one was eating plain wheat flour, what blessing would he recite? Rav Yehuda said that one recites: Who creates fruit of the ground, and Rav Naḥman said that one recites: By Whose word all things came to be.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא לְרַב נַחְמָן: לָא תִּפְלוֹג עֲלֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוּדָה, דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן וּשְׁמוּאֵל קָיְימִי כְּווֹתֵיהּ. דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל, וְכֵן אָמַר רַבִּי יִצְחָק אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: שֶׁמֶן זַיִת מְבָרְכִין עָלָיו ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָעֵץ״. אַלְמָא: אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִשְׁתַּנִּי — בְּמִלְּתֵיהּ קָאֵי. הָא נָמֵי, אַף עַל גַּב דְּאִשְׁתַּנִּי — בְּמִלְּתֵיהּ קָאֵי.

Rava said to Rav Naḥman: Do not disagree with Rav Yehuda, as Rabbi Yoḥanan and Shmuel hold in accordance with his opinion, even though they addressed another topic. As Rav Yehuda said that Shmuel said, and so too Rabbi Yitzḥak said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: One recites the blessing: Who creates fruit of the tree, over olive oil. Consequently, even though the olive has changed into olive oil, the formula of the blessing remains as it was. This too, even though the wheat has changed into flour, its blessing remains as it was: Who creates fruit of the ground.

מִי דָּמֵי? הָתָם — לֵית לֵיהּ עִלּוּיָא אַחֲרִינָא, הָכָא — אִית לֵיהּ עִלּוּיָא אַחֲרִינָא בְּפַת.

The Gemara responds: Is it comparable? There, the olive oil has no potential for additional enhancement, while here, the flour has the potential for additional enhancement as bread. Since oil is the olive’s finished product, one should recite the same blessing over it as over the tree itself. Wheat flour, on the other hand, is used to bake bread, so the flour is a raw material for which neither the blessing over wheat nor the blessing over bread is appropriate. Only the blessing: By Whose word all things came to be is appropriate.

וְכִי אִית לֵיהּ עִלּוּיָא אַחֲרִינָא לָא מְבָרְכִינַן עֲלֵיהּ ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״ אֶלָּא ״שֶׁהַכֹּל״? וְהָא אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא אָמַר רַב מַתְנָא אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: אַקָּרָא חַיָּיא וְקִמְחָא דִשְׂעָרֵי מְבָרְכִינַן עֲלַיְיהוּ ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיָה בִּדְבָרוֹ״. מַאי לָאו דְּחִיטֵּי בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה!

The Gemara asks: When it has a potential for additional enhancement, one does not recite: Who creates fruit of the ground; rather one recites: By Whose word all things came to be? Didn’t Rabbi Zeira say that Rav Mattana said that Shmuel said: Over a raw gourd and over barley flour, one recites the blessing: By Whose word all things came to be. What, is that not to say that over wheat flour one recites: Who creates fruit of the ground? Over barley flour, which people do not typically eat, it is appropriate to recite: By Whose word all things came to be. Over wheat flour, it is appropriate to recite: Who creates fruit of the ground.

לָא, דְּחִיטֵּי נָמֵי ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיָה בִּדְבָרוֹ״.

This argument is rejected: No, one also recites: By Whose word all things came to be, over wheat flour.

וְלַשְׁמְעִינַן דְּחִיטֵּי וְכׇל שֶׁכֵּן דִּשְׂעָרֵי!

The Gemara asks: Then let the Sages teach us that this halakha applies with regard to wheat flour, and all the more so regarding barley flour as well.

אִי אַשְׁמְעִינַן דְּחִיטֵּי הֲוָה אָמֵינָא הָנֵי מִילֵּי דְּחִיטֵּי, אֲבָל דִּשְׂעָרֵי לָא לְבָרֵיךְ עֲלֵיהּ כְּלָל, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara responds: It was necessary to teach us that one must recite a blessing even before eating barley flour. Had the Sages taught us this halakha with regard to wheat, I would have said: This applies only with regard to wheat flour, but over barley flour, let one not recite a blessing at all. Therefore, it teaches us that one recites a blessing over barley flour.

וּמִי גָּרַע מִמֶּלַח וְזָמִית, דִּתְנַן עַל הַמֶּלַח וְעַל הַזָּמִית אוֹמֵר ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיֶה בִּדְבָרוֹ״. אִצְטְרִיךְ, סָלְקָא דַעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא מֶלַח וְזָמִית עָבֵיד אִינָשׁ דְּשָׁדֵי לְפוּמֵּיהּ, אֲבָל קִמְחָא דִשְׂעָרֵי הוֹאִיל וְקָשֶׁה לְקוּקְיָאנֵי, לָא לְבָרֵיךְ עֲלֵיהּ כְּלָל, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן כֵּיוָן דְּאִית לֵיהּ הֲנָאָה מִינֵּיהּ בָּעֵי בָּרוֹכֵי.

The Gemara challenges this explanation. How could one have considered that possibility? Is it inferior to salt and salt water [zamit]? As we learned in a mishna that over salt and salt water one recites: By Whose word all things came to be, and all the more so it should be recited over barley flour. This question is rejected: Nevertheless, it was necessary to teach the halakha regarding barley flour, as it might enter your mind to say: Although one occasionally places salt or salt water into his mouth, barley flour, which is damaging to one who eats it and causes intestinal worms, let one recite no blessing over it at all. Therefore, it teaches us, since one derives pleasure from it, he must recite a blessing.

קוֹרָא, רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר: ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״, וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר: ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיֶה בִּדְבָרוֹ״.

Another dispute over the appropriate blessing is with regard to the heart of palm [kura], which is a thin membrane covering young palm branches that was often eaten. Rav Yehuda said that one should recite: Who creates fruit of the ground. And Shmuel, Rav Yehuda’s teacher, said that one should recite: By Whose word all things came to be.

רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״, פֵּירָא הוּא. וּשְׁמוּאֵל אָמַר ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיָה בִּדְבָרוֹ״, הוֹאִיל וְסוֹפוֹ לְהַקְשׁוֹת.

Rav Yehuda said: Who creates fruit of the ground; it is a fruit. And Shmuel said: By Whose word all things came to be, since it will ultimately harden and it is considered part of the tree, not a fruit.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ שְׁמוּאֵל לְרַב יְהוּדָה: שִׁינָּנָא, כְּווֹתָךְ מִסְתַּבְּרָא, דְּהָא צְנוֹן סוֹפוֹ לְהַקְשׁוֹת וּמְבָרְכִינַן עֲלֵיהּ ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״. וְלָא הִיא: צְנוֹן נָטְעִי אִינָשֵׁי אַדַּעְתָּא דְפוּגְלָא, דִּקְלָא לָא נָטְעִי אִינָשֵׁי אַדַּעְתָּא דְקוֹרָא.

Shmuel said to Rav Yehuda: Shinnana. It is reasonable to rule in accordance with your opinion, as a radish ultimately hardens if left in the ground; nevertheless, one who eats it while it is soft recites over it: Who creates fruit of the ground. In any case, despite this praise, the Gemara states: That is not so; people plant a radish with the soft radish in mind. However, people do not plant palm trees with the heart of palm in mind and therefore it cannot be considered a fruit.

וְכׇל הֵיכָא דְּלָא נָטְעִי אִינָשֵׁי אַדַּעְתָּא דְּהָכִי לָא מְבָרְכִינַן עֲלֵיהּ? וַהֲרֵי צָלָף, דְּנָטְעִי אִינָשֵׁי אַדַּעְתָּא דְפִרְחָא, וּתְנַן: עַל מִינֵי נִצְפָּה, עַל הֶעָלִין וְעַל הַתְּמָרוֹת אוֹמֵר ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״, וְעַל הָאֲבִיּוֹנוֹת וְעַל הַקַּפְרֵיסִין אוֹמֵר ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָעֵץ״.

In response to this, the Gemara asks: And whenever people do not plant with that result in mind, one does not recite a blessing over it? What of the caper-bush that people plant with their fruit in mind, and we learned in a mishna that with regard to the parts of the caper-bush [nitzpa], over the leaves and young fronds, one recites: Who creates fruit of the ground, and over the berries and buds he recites: Who creates fruit of the tree. This indicates that even over leaves and various other parts of the tree that are secondary to the fruit, the blessing is: Who creates fruit of the ground, and not: By Whose word all things came to be.

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק: צָלָף נָטְעִי אִינָשֵׁי אַדַּעְתָּא דְשׁוּתָא, דִּקְלָא לָא נָטְעִי אִינָשֵׁי אַדַּעְתָּא דְקוֹרָא. וְאַף עַל גַּב דְּקַלְּסֵיהּ שְׁמוּאֵל לְרַב יְהוּדָה, הִלְכְתָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דִּשְׁמוּאֵל.

Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak said that there is still a difference: Caper-bushes, people plant them with their leaves in mind; palm trees, people do not plant them with the heart of palm in mind. Therefore, no proof may be brought from the halakha in the case of the caper-bush to the halakha in the case of the of the palm. The Gemara concludes: Although Shmuel praised Rav Yehuda, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Shmuel.

אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: צָלָף שֶׁל עׇרְלָה בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ זוֹרֵק אֶת הָאֲבִיּוֹנוֹת וְאוֹכֵל אֶת הַקַּפְרֵיסִין. לְמֵימְרָא דַּאֲבִיּוֹנוֹת פֵּירֵי וְקַפְרֵיסִין לָאו פֵּירֵי? וּרְמִינְהוּ: עַל מִינֵי נִצְפָּה, עַל הֶעָלִים וְעַל הַתְּמָרוֹת אוֹמֵר ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״, וְעַל הָאֲבִיּוֹנוֹת וְעַל הַקַּפְרֵיסִין אוֹמֵר ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָעֵץ״!

Incidental to this discussion, the Gemara cites an additional halakha concerning the caper-bush. Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: A caper-bush during the first three years of its growth [orla] outside of Eretz Yisrael, when its fruits are prohibited by rabbinic and not Torah law, one throws out the berries, the primary fruit, but eats the buds. The Gemara raises the question: Is that to say that the berries are fruit of the caper, and the bud is not fruit? The Gemara raises a contradiction from what we learned in the mishna cited above: With regard to the parts of the caper-bush [nitzpa], over the leaves and young fronds, one recites: Who creates fruit of the ground, and over the berries, and buds he recites: Who creates fruit of the tree. Obviously, the buds are also considered the fruit of the caper-bush.

הוּא דְּאָמַר כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא. דִּתְנַן, רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: צָלָף מִתְעַשֵּׂר תְּמָרוֹת וַאֲבִיּוֹנוֹת וְקַפְרֵיסִין. רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: אֵין מִתְעַשֵּׂר אֶלָּא אֲבִיּוֹנוֹת בִּלְבַד, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהוּא פֶּרִי.

The Gemara responds: Rav’s statement is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva, as we learned in a mishna that Rabbi Eliezer says: A caper-bush is tithed from its component parts, its young fronds, berries and buds, as all these are considered its fruit. And Rabbi Akiva says: Only the berries alone are tithed, because it alone is considered fruit. It was in accordance with this opinion, that Rav prohibited only the eating of the berries during the caper-bush’s years of orla.

וְנֵימָא: ״הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא״! אִי אָמַר הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא אֲפִילּוּ בָּאָרֶץ, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן: כׇּל הַמֵּיקֵל בָּאָרֶץ — הֲלָכָה כְּמוֹתוֹ בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ, אֲבָל בָּאָרֶץ — לָא.

The Gemara asks: If this is the case, why did Rav issue what seemed to be an independent ruling regarding orla? He should have simply said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva, from which we could have drawn a practical halakhic conclusion regarding orla as well. The Gemara responds: Had Rav said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva, I would have said that the halakha is in accordance with his opinion even in Eretz Yisrael. Therefore, he teaches us by stating the entire halakha, that there is a principle: Anyone who is lenient in a dispute with regard to the halakhot of orla in Eretz Yisrael, the halakha is in accordance with his opinion outside of Eretz Yisrael, but not in Eretz Yisrael.

וְנֵימָא: ״הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ״, דְּכׇל הַמֵּיקֵל בָּאָרֶץ — הֲלָכָה כְּמוֹתוֹ בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ. אִי אָמַר הָכִי, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא הָנֵי מִילֵּי גַּבֵּי מַעְשַׂר אִילָן, דְּבָאָרֶץ גּוּפָא מִדְּרַבָּנַן, אֲבָל גַּבֵּי עׇרְלָה, דְּבָאָרֶץ מִדְּאוֹרָיְיתָא, אֵימָא בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ נָמֵי נִגְזוֹר, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara questions this: If so, then let Rav say: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva outside of Eretz Yisrael as anyone who is lenient in a dispute with regard to the halakhot of orla in Eretz Yisrael, the halakha is in accordance with his opinion outside of Eretz Yisrael. The Gemara answers: Had he said that, I would have said: That only applies with regard to the tithing of trees, which even in Eretz Yisrael itself is an obligation by rabbinic law; but with regard to orla, which is prohibited in Eretz Yisrael by Torah law, say that we should issue a decree prohibiting orla even outside of Eretz Yisrael. Therefore, he teaches us that even with regard to orla, the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva.

רָבִינָא אַשְׁכְּחֵיהּ לְמָר בַּר רַב אָשֵׁי דְּקָא זָרֵיק אֲבִיּוֹנוֹת וְקָאָכֵיל קַפְרֵיסִין. אֲמַר לֵיהּ: מַאי דַעְתָּךְ, כְּרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא דְּמֵיקֵל? וְלֶעֱבֵיד מָר כְּבֵית שַׁמַּאי דִּמְקִילִּי טְפֵי! דִּתְנַן: צָלָף, בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: כִּלְאַיִם בַּכֶּרֶם. וּבֵית הַלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: אֵין כִּלְאַיִם בַּכֶּרֶם. אֵלּוּ וְאֵלּוּ מוֹדִים שֶׁחַיָּיב בְּעׇרְלָה.

On this topic, the Gemara relates: Ravina found Mar bar Rav Ashi throwing away the berries and eating the buds of an orla caper-bush. Ravina said to Mar bar Rav Ashi: What is your opinion, that you are eating the buds? If it is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Akiva, who is lenient, then you should act in accordance with the opinion of Beit Shammai, who are even more lenient. As we learned in a mishna with regard to the laws of forbidden mixtures of diverse kinds that Beit Shammai say: A caper-bush is considered a diverse kind in the vineyard, as it is included in the prohibition against planting vegetables in a vineyard. Beit Hillel say: A caper-bush is not considered a diverse kind in a vineyard. Nevertheless, these and those, Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, agree that the caper-bush is obligated in the prohibition of orla.

הָא גוּפָא קַשְׁיָא: אָמְרַתְּ צָלָף בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים כִּלְאַיִם בַּכֶּרֶם, אַלְמָא מִין יָרָק הוּא, וַהֲדַר תָּנֵי: אֵלּוּ וְאֵלּוּ מוֹדִים שֶׁחַיָּיב בְּעׇרְלָה, אַלְמָא מִין אִילָן הוּא!

Before dealing with the problem posed by Ravina to Mar bar Rav Ashi, the Gemara notes an internal contradiction in this mishna. This mishna itself is problematic: You said that Beit Shammai say: A caper-bush is considered a diverse kind in a vineyard; apparently, they hold that it is a type of vegetable bush, and then you taught: These and those, Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, agree that the caper-bush is obligated in the prohibition of orla; apparently, it is a type of tree.

הָא לָא קַשְׁיָא: בֵּית שַׁמַּאי סַפּוֹקֵי מְסַפְּקָא לְהוּ, וְעָבְדִי הָכָא לְחוּמְרָא וְהָכָא לְחוּמְרָא. מִכׇּל מָקוֹם, לְבֵית שַׁמַּאי הָוֵה לֵיהּ סָפֵק עׇרְלָה, וּתְנַן: סָפֵק עׇרְלָה — בְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אָסוּר, וּבְסוּרְיָא מוּתָּר. וּבְחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ יוֹרֵד

The Gemara responds: This is not difficult; Beit Shammai are uncertain whether the caper-bush is a vegetable bush or a tree, and here, regarding diverse kinds, they act stringently and here, regarding orla, they act stringently. In any case, according to Beit Shammai the caper-bush has the status of uncertain orla, and we learned the consensus halakha in a mishna: Uncertain orla in Eretz Yisrael is forbidden to eat, and in Syria it is permitted, and we are not concerned about its uncertain status. Outside of Eretz Yisrael, the gentile owner of a field may go down into his field

וְלוֹקֵחַ — וּבִלְבַד שֶׁלֹּא יִרְאֶנּוּ לוֹקֵט.

and take from the orla fruit, and as long as the Jew does not see him gather it, he may purchase the fruit from the gentile. If so, then outside of Eretz Yisrael, one may act in accordance with the opinion of Beit Shammai who hold that the caper-bush has the status of uncertain orla, and eat even the berries without apprehension.

רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא בִּמְקוֹם רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר עָבְדִינַן כְּוָתֵיהּ, וּבֵית שַׁמַּאי בִּמְקוֹם בֵּית הִלֵּל — אֵינָהּ מִשְׁנָה.

The Gemara answers: The general rule that outside of Eretz Yisrael one acts in accordance with the lenient opinion in a dispute within Eretz Yisrael applies when Rabbi Akiva expresses a more lenient opinion in place of Rabbi Eliezer, and we act in accordance with his opinion. And however, when Beit Shammai express an opinion where Beit Hillel disagree, their opinion is considered as if it were not in the mishna, and is completely disregarded.

וְתִיפּוֹק לֵיהּ דְּנַעֲשָׂה שׁוֹמֵר לַפְּרִי, וְרַחֲמָנָא אָמַר: ״וַעֲרַלְתֶּם עׇרְלָתוֹ אֶת פִּרְיוֹ״, אֶת הַטָּפֵל לְפִרְיוֹ, וּמַאי נִיהוּ — שׁוֹמֵר לַפְּרִי.

The Gemara approaches this matter from a different perspective: Let us derive the halakha that buds are included in the prohibition of orla from the fact that the bud serves as protection for the fruit, and the Torah says: “When you enter the land and plant any tree for food you shall regard its fruit [et piryo] as orla” (Leviticus 19:23), and et piryo is interpreted to mean that which is secondary to the fruit. What is that? That section of the plant which is protection for the fruit. The buds should be prohibited as orla, since they protect the fruit.

אָמַר רָבָא: הֵיכָא אָמְרִינַן דְּנַעֲשָׂה שׁוֹמֵר לַפְּרִי — הֵיכָא דְּאִיתֵיהּ בֵּין בְּתָלוּשׁ בֵּין בִּמְחוּבָּר, הָכָא בִּמְחוּבָּר — אִיתֵיהּ, בְּתָלוּשׁ — לֵיתֵיהּ.

Rava said: Where do we say that a section of the plant becomes protection for the fruit? That is specifically when it exists both when the fruit is detached from the tree and when it is still connected to the tree. However, here, it exists when the fruit is connected to the tree, but when it is detached it does not, and since the protection falls off of the fruit when it is picked, it is no longer considered protection.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי: פִּיטְמָא שֶׁל רִמּוֹן מִצְטָרֶפֶת, וְהַנֵּץ שֶׁלּוֹ אֵין מִצְטָרֵף. מִדְּקָאָמַר הַנֵּץ שֶׁלּוֹ אֵין מִצְטָרֵף, אַלְמָא דְּלָאו אוֹכֶל הוּא. וּתְנַן גַּבֵּי עׇרְלָה: קְלִיפֵּי רִמּוֹן וְהַנֵּץ שֶׁלּוֹ, קְלִיפֵּי אֱגוֹזִים וְהַגַּרְעִינִין חַיָּיבִין בְּעׇרְלָה.

Abaye raised a challenge based on what we learned with regard to the halakhot of ritual impurity: The crown of a pomegranate joins together with the pomegranate as a unified entity with regard to calculating the requisite size in order to become ritually impure. And its flower, however, does not join together with the pomegranate in that calculation. From the fact that it says that the pomegranate’s flower does not join, consequently the flower is secondary to the fruit and is not considered food. And we learned in a mishna regarding the laws of orla: The rinds of a pomegranate and its flower, nutshells, and pits of all kinds, are all obligated in the prohibition of orla. This indicates that the criteria dictating what is considered protection of a fruit and what is considered the fruit itself with regard to ritual impurity, are not the same criteria used with regard to orla, as is illustrated by the case of the pomegranate flower. Therefore, even if the buds are not regarded as protecting the fruit with regard to ritual impurity, they may still be considered fruit with regard to orla.

אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבָא: הֵיכָא אָמְרִינַן דְּנַעֲשָׂה לְהוּ שׁוֹמֵר לְפֵירֵי — הֵיכָא דְּאִיתֵיהּ בִּשְׁעַת גְּמַר פֵּירָא, הַאי קַפְרֵס לֵיתֵיהּ בִּשְׁעַת גְּמַר פֵּירָא.

Rather, Rava said another explanation: Where do we say that a section of the plant becomes protection for the fruit? Where it exists when the fruit is ripe. This bud does not exist when the fruit is ripe, because it falls off beforehand.

אִינִי?! וְהָאָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ: הָנֵי מְתַחֲלֵי דְעׇרְלָה אֲסִירִי, הוֹאִיל וְנַעֲשׂוּ שׁוֹמֵר לְפֵירֵי. וְשׁוֹמֵר לְפֵירֵי אִימַּת הָוֵי — בְּכוּפְרָא, וְקָא קָרֵי לֵיהּ ״שׁוֹמֵר לְפֵירֵי״.

The Gemara challenges this explanation as well: Is that so? Didn’t Rav Naḥman say that Rabba bar Avuh said: Those orla date coverings are prohibited, because they became protection for the fruit. And when do these coverings serve as protection for the fruit? When the fruit is still young; and he, nevertheless, calls them protection for the fruit. This indicates that in order to be considered protection for the fruit it need not remain until the fruit is fully ripened. The question remains: Why are the buds not accorded the same status as the berries of the caper-bush?

רַב נַחְמָן סָבַר לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי, דִּתְנַן רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: סְמָדַר אָסוּר מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהוּא פֶּרִי. וּפְלִיגִי רַבָּנַן עֲלֵיהּ.

The Gemara explains that Rav Naḥman held in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei, as we learned in a mishna that Rabbi Yosei says: The grape-bud, i.e., a cluster of grapes in its earliest stage, immediately after the flowers dropped from the vine, is prohibited due to orla, because it is already considered a fruit. According to this opinion, even the date coverings that exist in the earliest stage of the ripening process are nevertheless considered protection for the fruit and prohibited due to orla. The Rabbis disagree with him, explaining that fruit at that stage is not considered fruit; and, therefore, the date coverings and caper-bush buds are not considered protection for the fruit and are not prohibited due to orla.

מַתְקִיף לַהּ רַב שִׁימִי מִנְּהַרְדְּעָא: וּבִשְׁאָר אִילָנֵי מִי פְּלִיגִי רַבָּנַן עֲלֵיהּ? וְהָתְנַן: מֵאֵימָתַי אֵין קוֹצְצִין אֶת הָאִילָנוֹת בַּשְּׁבִיעִית — בֵּית שַׁמַּאי אוֹמְרִים: כׇּל הָאִילָנוֹת מִשֶּׁיּוֹצִיאוּ, וּבֵית הִלֵּל אוֹמְרִים: הֶחָרוּבִין מִשֶּׁיְּשַׁרְשְׁרוּ, וְהַגְּפָנִים מִשֶּׁיְּגָרְעוּ, וְהַזֵּיתִים מִשֶּׁיָּנֵיצוּ, וּשְׁאָר כׇּל הָאִילָנוֹת מִשֶּׁיּוֹצִיאוּ.

Rav Shimi of Neharde’a strongly objects to this halakha: Do the Rabbis disagree with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei with regard to the fruits of all other trees besides grapes, that even in the very first stage of ripening, they are considered fruit? Didn’t we learn in a mishna: With regard to fruit, which grows during the Sabbatical year, the Torah says: “And the Shabbat of the land shall be to you for eating” (Leviticus 25:6). The Sages inferred, for eating, and not for loss. Because one is prohibited from discarding fruit grown during the Sabbatical year, the question is raised: From when may one no longer cut trees during the Sabbatical year as he thereby damages the fruit? Beit Shammai say: All trees, from when the blossoms fall off and fruit begins to emerge in its earliest stage. And Beit Hillel say: There is a distinction between different types of trees. Carob trees may not be cut from when they form chains of carobs, vines may not be cut misheyegaru, explained below, olives from when they blossom, and all other trees from when fruit emerges.

וְאָמַר רַב אַסִּי: הוּא בּוֹסֶר, הוּא גֵּרוּעַ, הוּא פּוֹל הַלָּבָן. פּוֹל הַלָּבָן סָלְקָא דַעְתָּךְ?! אֶלָּא אֵימָא: שִׁיעוּרוֹ כְּפוֹל הַלָּבָן. מַאן שָׁמְעַתְּ לֵיהּ דְּאָמַר בּוֹסֶר אִין, סְמָדַר לָא — רַבָּנַן, וְקָתָנֵי שְׁאָר כׇּל הָאִילָנוֹת — מִשֶּׁיּוֹצִיאוּ?

And Rav Asi said: Sheyegaru in our mishna is to be understood: It is an unripe grape, it is a grape kernel, it is a white bean. Before this is even explained, the Gemara expresses its astonishment: Does it enter your mind that the grape is, at any stage, a white bean? Rather, say: Its size, that of an unripe grape, is equivalent to the size of a white bean. In any case, whom did you hear that said: An unripe grape, yes, is considered fruit, while a grape-bud, no, is not considered fruit? Wasn’t it the Rabbis who disagree with Rabbi Yosei, and it is taught that, according to these Sages, one is forbidden to cut all other trees from when fruit emerges. This indicates that even they agree that from the very beginning of the ripening process, the fruit is forbidden due to orla. The question remains: Why are the buds permitted?

אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבָא: הֵיכָא אָמְרִינַן דְּהָוֵי שׁוֹמֵר לְפֵרֵי — הֵיכָא דְּכִי שָׁקְלַתְּ לֵיהּ לְשׁוֹמֵר מָיֵית פֵּירָא. הָכָא כִּי שָׁקְלַתְּ לֵיהּ — לָא מָיֵית פֵּירָא.

Rather, Rava said a different explanation: Where do we say that a section of the plant becomes protection for the fruit? Where if you remove the protection, the fruit dies. Here, in the case of the caper-bush, when you remove the bud, the fruit does not die.

הֲוָה עוֹבָדָא וְשַׁקְלוּהּ לְנֵץ דְּרִמּוֹנָא, וִיבַשׁ רִמּוֹנָא, וְשַׁקְלוּהּ לְפִרְחָא דְבִיטִיתָא — וְאִיקַּיַּים בִּיטִיתָא.

In fact, there was an incident and they removed the flower of a pomegranate, and the pomegranate withered. And they removed the flower of the fruit of a caper-bush and the fruit of the caper-bush survived. Therefore, buds are not considered protection for the fruit.

(וְהִלְכְתָא כְּמָר בַּר רַב אָשֵׁי דְּזָרֵיק אֶת הָאֲבִיּוֹנוֹת וְאָכֵיל אֶת הַקַּפְרֵיסִין. וּמִדִּלְגַבֵּי עׇרְלָה לָאו פֵּירָא נִינְהוּ, לְגַבֵּי בְּרָכוֹת נָמֵי לָאו פֵּירָא נִינְהוּ, וְלָא מְבָרְכִינַן עֲלֵיהּ ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָעֵץ״, אֶלָּא ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״.)

The Gemara concludes: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Mar bar Rav Ashi, who discarded the berries and ate the buds. And since they are not considered fruit with regard to orla, they are also not considered fruit with regard to blessings, and one does not recite over them: Who creates fruit of the tree, but rather: Who creates fruit of the ground.

פִּלְפְּלֵי, רַב שֵׁשֶׁת אָמַר: ״שֶׁהַכֹּל״, רָבָא אָמַר: לָא כְלוּם. וְאָזְדָא רָבָא לְטַעְמֵיהּ, דְּאָמַר רָבָא: כַּס פִּלְפְּלֵי בְּיוֹמָא דְכִפּוּרֵי — פָּטוּר, כַּס זַנְגְּבִילָא בְּיוֹמָא דְכִפּוּרֵי — פָּטוּר.

The question arose with regard to the blessing over peppers. Rav Sheshet said: One who eats peppers must recite: By Whose word all things came to be. Rava said: One need not recite a blessing at all. This is consistent with Rava’s opinion that eating peppers is not considered eating, as Rava said: One who chews on peppers on Yom Kippur is exempt, one who chews on ginger on Yom Kippur is exempt. Eating sharp spices is an uncommon practice, and is therefore not considered to be eating, which is prohibited by Torah law on Yom Kippur.

מֵיתִיבִי, הָיָה רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: מִמַּשְׁמַע שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ״וַעֲרַלְתֶּם עׇרְלָתוֹ אֶת פִּרְיוֹ״ אֵינִי יוֹדֵעַ שֶׁעֵץ מַאֲכָל הוּא? אֶלָּא מָה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״עֵץ מַאֲכָל״ — לְהָבִיא עֵץ שֶׁטַּעַם עֵצוֹ וּפִרְיוֹ שָׁוֶה, וְאֵיזֶהוּ? — זֶה הַפִּלְפְּלִין. לְלַמֶּדְךָ שֶׁהַפִּלְפְּלִין חַיָּיבִין בְּעׇרְלָה, וּלְלַמֶּדְךָ שֶׁאֵין אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל חֲסֵרָה כְּלוּם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״אֶרֶץ אֲשֶׁר לֹא בְמִסְכֵּנֻת תֹּאכַל בָּהּ לֶחֶם לֹא תֶחְסַר כֹּל בָּהּ״.

The Gemara raised an objection to this based on what was taught in a baraita, that regarding the verse: “When you enter the land and plant any tree for food you shall regard its fruit as orla” (Leviticus 19:23), Rabbi Meir would say: By inference from that which is stated: “You shall regard its fruit as orla,” don’t I know that it is referring to a tree that produces food? Rather, for what purpose does the verse state: “Any tree for food”? To include a tree whose wood and fruit have the same taste. And which tree is this? This is the pepper tree. And this comes to teach you that the peppers, and even the wood portions, are edible and are therefore obligated in the prohibition of orla, and to teach that Eretz Yisrael lacks nothing, as it is stated: “A land where you shall eat bread without scarceness, you shall lack nothing” (Deuteronomy 8:9). Obviously, peppers are fit for consumption.

לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָא בְּרַטִּיבְתָּא, הָא בְּיַבִּשְׁתָּא.

The Gemara responds: This is not difficult, as there is a distinction between two different cases. This, where Rabbi Meir spoke of peppers fit for consumption, is referring to a case when it is damp and fresh; and this, where chewing on pepper is not considered eating on Yom Kippur and does not require a blessing, is referring to a case when it is dry.

אָמְרִי לֵיהּ רַבָּנַן לְמָרִימָר: כַּס זַנְגְּבִילָא בְּיוֹמָא דְכִפּוּרֵי פָּטוּר? וְהָא אָמַר רָבָא: הַאי הִמְלְתָא דְּאָתְיָא מִבֵּי הִנְדּוּאֵי — שַׁרְיָא, וּמְבָרְכִינַן עֲלַהּ ״בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה״. לָא קַשְׁיָא: הָא בְּרַטִּיבְתָּא, הָא בְּיַבִּשְׁתָּא.

With regard to this discussion of chewing pepper on Yom Kippur, the Gemara cites what the Sages said to Mareimar: Why is one who chews ginger on Yom Kippur exempt? Didn’t Rava say: One is permitted to eat the ginger that comes from India, and over it, one recites: Who creates fruit of the ground. With regard to blessing, it is considered edible; therefore, with regard to chewing on Yom Kippur, it should be considered edible as well. The Gemara responds: This is not difficult. This, where a blessing is recited, is referring to a case when it is damp and fresh; this, where no blessing is recited, is referring to a case when it is dry.

חֲבִיץ קְדֵרָה וְכֵן דַּיְיסָא, רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר: ״שֶׁהַכֹּל נִהְיֶה בִּדְבָרוֹ״. רַב כָּהֲנָא אָמַר: ״בּוֹרֵא מִינֵי מְזוֹנוֹת״. בְּדַיְיסָא גְּרֵידָא כּוּלֵּי עָלְמָא לָא פְּלִיגִי דְּ״בוֹרֵא מִינֵי מְזוֹנוֹת״. כִּי פְּלִיגִי בְּדַיְיסָא כְּעֵין חֲבִיץ קְדֵרָה, רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר ״שֶׁהַכֹּל״, סָבַר דּוּבְשָׁא עִיקָּר. רַב כָּהֲנָא אָמַר ״בּוֹרֵא מִינֵי מְזוֹנוֹת״, סָבַר סְמִידָא עִיקָּר. אָמַר רַב יוֹסֵף: כְּוָתֵיהּ דְּרַב כָּהֲנָא מִסְתַּבְּרָא, דְּרַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: כֹּל שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ מֵחֲמֵשֶׁת הַמִּינִין מְבָרְכִין עָלָיו ״בּוֹרֵא מִינֵי מְזוֹנוֹת״.

The Gemara cites a similar dispute with regard to the blessing be recited over ḥavitz, a dish consisting of flour, oil, and honey cooked in a pot as well as pounded grain. Rav Yehuda said that one recites: By Whose word all things came to be. Rav Kahana said that one recites: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment. The Gemara explains: With regard to pounded grain alone, everyone agrees that one recites: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment. When they argue, it is with regard to pounded grain mixed with honey, in the manner of a ḥavitz cooked in a pot. Rav Yehuda said that one recites: By Whose word all things came to be, as he held that the honey is primary, and on honey one recites: By Whose word all things came to be. Rav Kahana said that one recites: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment, as he held that the flour, as is the case with all products produced from grain, is primary, and therefore one recites: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment. Rav Yosef said: It is reasonable to say in accordance with the opinion of Rav Kahana, as Rav and Shmuel both said: Anything that has of the five species of grain in it, one recites over it: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment, even if it is mixed with other ingredients.

גּוּפָא: רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ כֹּל שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ מֵחֲמֵשֶׁת הַמִּינִין מְבָרְכִין עָלָיו ״בּוֹרֵא מִינֵי מְזוֹנוֹת״. וְאִיתְּמַר נָמֵי, רַב וּשְׁמוּאֵל דְּאָמְרִי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ: כֹּל שֶׁהוּא מֵחֲמֵשֶׁת הַמִּינִין מְבָרְכִין עָלָיו בּוֹרֵא מִינֵי מְזוֹנוֹת.

With regard to the halakha of the blessing recited over the five species of grain, the Gemara clarifies the matter itself. Rav and Shmuel both said: Anything that has of the five species of grain in it, one recites over it: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment. Elsewhere, it was stated that Rav and Shmuel both said: Anything that is from the five species of grain, one recites over it: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment. This is problematic, as these statements appear redundant.

וּצְרִיכָא, דְּאִי אַשְׁמְעִינַן ״כֹּל שֶׁהוּא״ הֲוָה אָמֵינָא מִשּׁוּם דְּאִיתֵיהּ בְּעֵינֵיהּ, אֲבָל עַל יְדֵי תַּעֲרוֹבוֹת — לָא.

The Gemara explains: Both statements are necessary, as had he taught us only: Anything that is from the five species of grain, one recites over it: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment, I would have said that is because the grain is in its pure, unadulterated form, but if one eats it in the context of a mixture, no, one does not recite: Who creates the various kinds of nourishment.