More laws regarding different items joining together – orla and grain sown in a vineyard. Also different materials regarding impurities. In order to be olbigated for meilah, does one need to both benefit and also damage the item? On what does it depend? A braita brings several drashot regarding meilah from the verse in the Torah, including that if one sends a messenger to misuse consecrated property, the one who sent the messenger is obligated (even though usually we hold there is no messenger when it comes to sinning).

Meilah 18

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

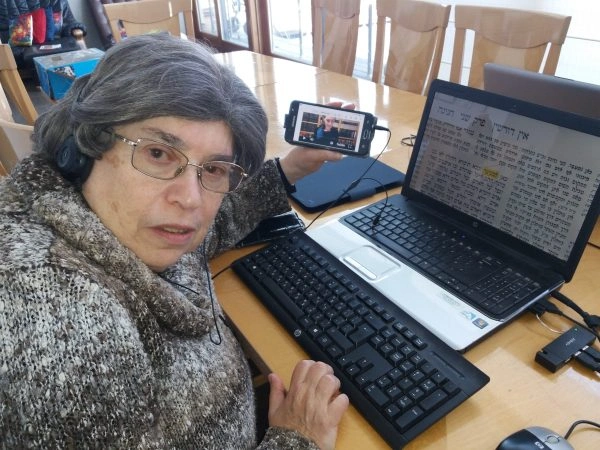

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Meilah 18

מַתְנִי׳ הָעׇרְלָה וְכִלְאֵי הַכֶּרֶם – מִצְטָרְפִין זֶה עִם זֶה. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: אֵין מִצְטָרְפִין.

MISHNA: The fruit of a tree during the first three years after its planting [orla] (see Leviticus 19:23), and diverse kinds,i.e., grain sown in a vineyard (see Deuteronomy 22:9) join together to constitute the requisite measure to prohibit a mixture that they are mixed into. This applies when the volume of the permitted produce is less than two hundred times the prohibited produce. Rabbi Shimon says: They do not join together.

גְּמָ׳ וּמִי צָרִיךְ רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן לְצָרוֹפֵי? וְהָתַנְיָא, רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: כׇּל שֶׁהוּא לְמַכּוֹת? תְּנִי: אֵין צְרִיכִין לְצָרֵף.

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: And according to Rabbi Shimon, do the two half-measures need to join together, in order for one who eats them to be liable? But isn’t it taught in a baraita that Rabbi Shimon says: One who eats any measure of a prohibited food is liable to receive lashes, as the Sages stated the measure of an olive-bulk only with regard to the requirement to bring an offering? The Gemara answers: The wording of the mishna is not precise and must be emended, to teach that Rabbi Shimon says: They do not need to join together, as one is flogged even for less than the minimum measure.

מַתְנִי׳ הַבֶּגֶד וְהַשַּׂק, הַשַּׂק וְהָעוֹר, הָעוֹר וְהַמַּפָּץ – כּוּלָּן מִצְטָרְפִין זֶה עִם זֶה.

MISHNA: A garment must be at least three by three handbreadths in order to become a primary source of ritual impurity, by means of ritual impurity imparted by the treading of a zav. A sack made from goats’ hair must be at least four by four handbreadths, while an animal hide must be five by five, and a mat six by six. The garment and the sack, the sack and the hide, and the hide and the mat all join together to constitute the requisite measure to become ritually impure in accordance with the material of the greater measure.

אָמַר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן: מָה טַעַם? מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהֵן רְאוּיִן לִיטָּמֵא בְּמוֹשָׁב.

Rabbi Shimon said: What is the reason that they join together, despite the fact that their requisite measures are not equal? Because all the component materials are fit to become ritually impure through the ritual impurity imparted to a seat upon which a zav sits, as they can each be used to patch a saddle or saddlecloth. Since the measure of all these materials is equal in the case of a zav, they join together for other forms of ritual impurity as well.

גְּמָ׳ תָּנָא: קִיצַּע מִכּוּלָּן שְׁלֹשָׁה, וְעָשָׂה מֵהֶן בֶּגֶד לְמִשְׁכָּב – שְׁלֹשָׁה, לְמוֹשָׁב – טֶפַח, לַאֲחִיזָה – כׇּל שֶׁהוּ.

GEMARA: A Sage taught in a baraita: In a case where one cut from each of the materials listed in the mishna, i.e., the garment, the sack, the hide, and the mat, a piece of less than three by three handbreadths, and sewed them together, thereby fashioning a garment from them; if he formed the garment for lying upon it, then the minimum measure for it to become a primary source of ritual impurity is three handbreadths. If he intended it for sitting, the minimum measure is one handbreadth. If he intended to use it for holding, it becomes impure in any measure.

מַאי לַאֲחִיזָה? אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ, אָמַר רַבִּי יַנַּאי: שֶׁכֵּן עוֹמֵד לְנַוְולָה. בְּמַתְנִיתָא תָּנָא: הוֹאִיל וְרָאוּי לְקוֹצְצֵי תְאֵנִים.

The Gemara asks: What is the reason for the halakha in the case where one intended to use it for holding? Why is this cloth classified as a garment? Reish Lakish says that Rabbi Yannai says: It is considered a garment because it stands to be used as protection for the hands when weaving [lenavla], so that the weaver does not cut his fingers when straightening the threads. It was taught in a baraita: It is considered a garment since it is suited for fig cutters to place the material on their hands, to prevent them from getting dirty.

הַדְרָן עֲלָךְ קׇדְשֵׁי מִזְבֵּחַ

הַנֶּהֱנֶה מִן הַהֶקְדֵּשׁ שָׁוֶה פְּרוּטָה, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁלֹּא פָּגַם – מָעַל, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: כׇּל דָּבָר שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ פְּגָם – לֹא מָעַל, עַד שֶׁיִּפְגּוֹם. וְשֶׁאֵין בּוֹ פְּגָם, כֵּיוָן שֶׁנֶּהֱנָה – מָעַל.

MISHNA: One who derives benefit equal to the value of one peruta from a consecrated item, even though he did not damage it, is liable for its misuse; this is the statement of Rabbi Akiva. And the Rabbis say: With regard to any consecrated item that has the potential to be damaged, one is not liable for misuse until he causes it one peruta of damage; and with regard to an item that does not have the potential to be damaged, once he derives benefit from it he is liable for misuse.

כֵּיצַד? נָתְנָה קַטְלָא בְּצַוָּארָהּ, טַבַּעַת בְּיָדָהּ, שָׁתָה בְּכוֹס שֶׁל זָהָב, כֵּיוָן שֶׁנֶּהֱנָה – מָעַל. לָבַשׁ בְּחָלוּק, כִּסָּה בְּטַלִּית, בִּיקַּע בְּקַרְדּוֹם – לֹא מָעַל עַד שֶׁיִּפְגּוֹם.

The mishna elaborates: How so? If a woman placed a consecrated gold chain [ketala] around her neck, or a gold ring on her hand, i.e., her finger, or if one drank from a consecrated gold cup, since they are not damaged through use, once he derives benefit equal to the value of one peruta from them, he is liable for misuse. If one wore a consecrated robe, covered himself with a consecrated garment, or chopped wood with a consecrated ax, he is not liable for misuse until he causes them one peruta of damage.

הַנֶּהֱנֶה מִן הַחַטָּאת, כְּשֶׁהִיא חַיָּה – לֹא מָעַל, עַד שֶׁיִּפְגּוֹם. כְּשֶׁהִיא מֵתָה, כֵּיוָן שֶׁנֶּהֱנָה – מָעַל.

One who derives benefit from a sin offering while it is alive is not liable for misuse until he causes it one peruta of damage. When it is dead, once he derives benefit equal to the value of one peruta from it, he is liable for misuse.

גְּמָ׳: תָּנָא: מוֹדֶה רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא לַחֲכָמִים בְּדָבָר שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ פְּגָם. בְּמַאי קָא מִיפַּלְגִי?!

GEMARA: The Sages taught in a baraita: Rabbi Akiva concedes to the Rabbis in the case of an item that has the potential to be damaged through its use that one is liable for misuse only if he causes one peruta of damage. The Gemara asks: Since this is apparently exactly the same as the opinion of the Rabbis, with regard to what do Rabbi Akiva and the Rabbis disagree?

אָמַר רָבָא: בִּלְבוּשׁ מְצִיעָאָה, וּמַלְמְלָא.

Rava said: With regard to outer garments such as coats, which are exposed to the weather and other elements, and garments worn touching the skin, which can be damaged by perspiration, Rabbi Akiva and the Rabbis agree that one is liable for misuse only when the garments are damaged at least by the value of one peruta. They disagree in the case of a middle garment, i.e., that which is neither an outer garment nor one that is worn against the body. And they also disagree in the case of a garment made of malmala, very thin fabric; since this garment is expensive, one who wears it would be very careful not to let it be damaged, and consequently it is not subject to measurable depreciation each time it is worn. In these cases, Rabbi Akiva holds that one is liable for misuse if he derives benefit equal to the value of one peruta even though the garments were not depreciated by one peruta, whereas the Rabbis maintain that as there is cumulative depreciation, one is liable for misuse only when he causes one peruta of damage.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״נֶפֶשׁ״ – אֶחָד הַיָּחִיד, וְאֶחָד הַנָּשִׂיא, וְאֶחָד הַמָּשִׁיחַ.

§ The Sages taught in a baraita: With regard to misuse of consecrated property, the verse states: “If anyone commits a misuse, and sins through error, in the sacred items of the Lord” (Leviticus 5:15). It is derived from the general term “anyone” that this halakha applies whether the guilty person is a common individual, and whether he is the king, and whether he is the anointed High Priest. Although in other contexts they have obligations to bring different offerings, these individuals have a uniform liability with regard to the sin of misuse.

״כִּי תִמְעֹל מַעַל״, אֵין ״מַעַל״ אֶלָּא שִׁנּוּי, וְכֵן הוּא אוֹמֵר: ״אִישׁ אִישׁ כִּי תִשְׂטֶה אִשְׁתּוֹ וּמָעֲלָה בוֹ מַעַל״, וְאוֹמֵר: ״וַיִּמְעֲלוּ בֵּאלֹהֵי

The baraita further interprets the verse: “If anyone commits a misuse [ma’al], and sins” (Leviticus 5:15). The term ma’al means nothing other than deviation from the norm. And similarly, the verse states with regard to a woman suspected of adultery: “If any man’s wife goes aside, and acts unfaithfully [ma’al] against him” (Numbers 5:12). And it states with regard to idol worship: “And they broke faith [vayimalu] with the God of

אֲבֹתֵיהֶם וַיִּזְנוּ אַחֲרֵי הַבְּעָלִים״.

their fathers, and went astray after the gods of the peoples of the land, whom God destroyed before them” (I Chronicles 5:25). Likewise, one who misuses consecrated property deviates from the purpose for which the particular item was meant to be used.

יָכוֹל פָּגַם וְלֹא נֶהֱנָה, אוֹ נֶהֱנָה וְלֹא פָּגַם,

The baraita continues: One might have thought that the comparison between misuse and idol worship teaches that one is liable for misuse even if he damaged the consecrated item but did not derive benefit from it, as that is the halakha with regard to idol worship, where one changes worship of God to idol worship without deriving benefit. Or, in light of the comparison between misuse and suspected adultery, it might have been thought that one would be liable for misuse if he derived benefit from the consecrated item but did not damage it, just as the adulteress derives benefit from the illicit act of intercourse without suffering any physical damage.

וּבִמְחוּבָּר לַקַּרְקַע, וּבְשָׁלִיחַ שֶׁעָשָׂה שְׁלִיחוּתוֹ?

And perhaps one should be liable for misuse of an item attached to the ground. And in the case of an agent who committed misuse while he performed his assigned agency, it might be thought that the agent himself, rather than the one who appointed him, should be liable for the misuse.

תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר ״וְחָטְאָה״. נֶאֱמַר: ״חֵטְא״ בִּתְרוּמָה, וְנֶאֱמַר: ״חֵטְא״ בִּמְעִילָה.

The halakha in these cases is derived from the fact that the verse states: “If anyone commits a misuse, and sins through error, in the sacred items of the Lord” (Leviticus 5:15). The word “sin” is stated with regard to teruma, in the verse: “And you shall bear no sin by reason of it, as you have set apart from it its best” (Numbers 18:32); and “sin” is also stated with regard to misuse of consecrated property. Several halakhot are derived from this verbal analogy.

מָה ״חֵטְא״ הָאָמוּר בִּתְרוּמָה, פּוֹגֵם וְנֶהֱנֶה, וּמִי שֶׁפָּגַם נֶהֱנֶה, וּבַדָּבָר שֶׁפּוֹגֵם בּוֹ נֶהֱנֶה, וּפְגִימָתוֹ וַהֲנָאָתוֹ כְּאֶחָד, וּבְתָלוּשׁ מִן הַקַּרְקַע, וּבְשָׁלִיחַ שֶׁעָשָׂה שְׁלִיחוּתוֹ –

The baraita elaborates: Just as with regard to the word “sin” stated with regard to teruma, when someone sins by partaking of forbidden teruma, it is a circumstance in which one damages and derives benefit, and the one who damaged the teruma is the same person who derived benefit; and with regard to teruma, one is liable only if he derives benefit from the same item that he damages; and he is liable in the case of teruma only if his damage and his benefit occur simultaneously; and the status of teruma applies only to an item detached from the ground; and the status of teruma takes effect in the case of an agent who performed his assigned agency in designating an item teruma, the same applies to misuse.

אַף ״חֵטְא״ הָאָמוּר בִּמְעִילָה, פּוֹגֵם וְנֶהֱנֶה, וּמִי שֶׁפָּגַם נֶהֱנֶה, וּבַדָּבָר שֶׁפּוֹגֵם בּוֹ נֶהֱנֶה, וּפְגִימָתוֹ וַהֲנָאָתוֹ כְּאֶחָד, וּבְתָלוּשׁ מִן הַקַּרְקַע, וּבְשָׁלִיחַ שֶׁעָשָׂה שְׁלִיחוּתוֹ.

The baraita further explains: So too, the word “sin” stated with regard to misuse applies specifically when the individual both damages and derives benefit from consecrated items; and when the one who damaged also derived benefit from it himself; and he derives benefit from the same item that he damages; and his damage and his deriving benefit occur simultaneously; and misuse applies only to an item detached from the ground; and misuse is committed by the one appointing the agent in the case of an agent who performed his assigned agency.

אֵין לִי אֶלָּא אוֹכֵל, וְנֶהֱנֶה בְּדָבָר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ פְּגָם, מִנַּיִן?

The baraita continues: From the verbal analogy I have derived only that one is liable for misuse if he eats consecrated items when he is not permitted to do so, similar to the case of teruma. But with regard to one who derives benefit from an item that does not have the potential to be damaged, from where do I derive that this also constitutes misuse?

אֲכִילָתוֹ וַאֲכִילַת חֲבֵרוֹ, הֲנָיָיתוֹ וַהֲנָיַית חֲבֵרוֹ, הֲנָאָתוֹ וַאֲכִילַת חֲבֵרוֹ, אֲכִילָתוֹ וַהֲנָיַית חֲבֵרוֹ שֶׁמִּצְטָרְפִין זֶה עִם זֶה, אֲפִילּוּ לִזְמַן מְרוּבֶּה, מִנַּיִן?

Similarly, if one eats from a consecrated item and gives to another person to eat, where there is his consumption and another’s consumption; or if he derives benefit and gives to another to derive benefit, where there is his deriving benefit and another’s deriving benefit; and likewise his deriving benefit and another’s consumption; and his consumption and another’s deriving benefit; the halakha is that in all these cases, benefit and consumption combine with one another, even over a long period of time on the same day, to amount to the value of one peruta that effects liability for misuse. From where is this halakha derived?

תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״תִּמְעֹל מַעַל״ – מִכׇּל מָקוֹם.

The verse states: “If anyone commits a misuse.” This general and inclusive clause teaches that one is liable for misusing one peruta worth of consecrated property in any case, i.e., even if he gave it to another and one of them ate while the other derived benefit, and even if it took some time on that day to use the value of one peruta.

אִי מָה ״חֵטְא״ הָאָמוּר בִּתְרוּמָה – לֹא צֵירַף שְׁתֵּי אֲכִילוֹת כְּאֶחָד, אַף ״חֵטְא״ הָאָמוּר בִּמְעִילָה – לֹא צֵירַף שְׁתֵּי אֲכִילוֹת כְּאַחַד. מִנַּיִן אָכַל הַיּוֹם וְאָכַל לְמָחָר, וַאֲפִילּוּ לִזְמַן מְרוּבֶּה? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״תִּמְעֹל מַעַל״ – מִכׇּל מָקוֹם.

The baraita further states: If there is a comparison between teruma and misuse, one can claim as follows: Just as in the case of the word “sin” that is stated with regard to teruma, the Torah does not combine two distinct acts of consumption as one prohibited act, so too, perhaps with regard to the word “sin” that is stated with regard to misuse, the Torah does not combine two acts of consumption as one. From where is it derived that if one ate half of the minimum amount of an olive-bulk today and ate another half tomorrow, even if much time has passed, the distinct acts of misuse combine and are considered one act, which means that the one who did so is liable for misuse? The verse states: “If anyone commits a misuse.” The inclusive language of the verse teaches that he is liable in any case.

אִי מָה ״חֵטְא״ הָאָמוּר בִּתְרוּמָה – פְּגִימָתוֹ וַהֲנָאָתוֹ כְּאֶחָד, מִנַּיִן לַאֲכִילָתוֹ וַאֲכִילַת חֲבֵרוֹ? וַאֲפִילּוּ מִכָּאן וְעַד שָׁלֹשׁ שָׁנִים, מִנַּיִן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״תִּמְעֹל מַעַל״ – מִכׇּל מָקוֹם.

The baraita continues: If there is a comparison between teruma and misuse, one can claim as follows: Just as in the case of the word “sin” that is stated with regard to teruma, the damage to the teruma and the individual’s deriving benefit from the teruma occur simultaneously, the same should apply to misuse of consecrated items. From where is it derived that one is liable for misuse for his consumption and another’s consumption, when each person alone has eaten less than the value of one peruta, and even if the two acts of consumption are separated in time from now until three years later; from where is it derived that the instances of misuse combine? The verse states: “If anyone commits a misuse.” The inclusive language of the verse teaches that he is liable in any case.

אִי מָה ״חֵטְא״ הָאָמוּר בִּתְרוּמָה

The baraita continues: If it is derived from the verbal analogy that there are several halakhot common to both teruma and committing misuse, one can claim as follows: Just as in the case of the word “sin” that is stated with regard to teruma,