The gemara brings more sources to resolve the issue of whether or the moment of the meat being considered permitted to priests is the moment of accepting the blood (enabling the sprinkling) or the moment of sprinkling the blood (enabling the meat to be eaten). Each source is explained according to each approach and therefore there is no resolution. If the meat is disqualified because it left the courtyard of the Beit Hamikdash, and the sprinkling of the blood is effective to effect atonement, but not to permit the meat to be eaten, is that blood sprinkling effective to change the status of the meat regarding meilah (to remove meilah from higher level sanctified meat and add meilah to the parts of the lower level sanctified parts of the meat that are generally burned on the altar)?

Meilah 6

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

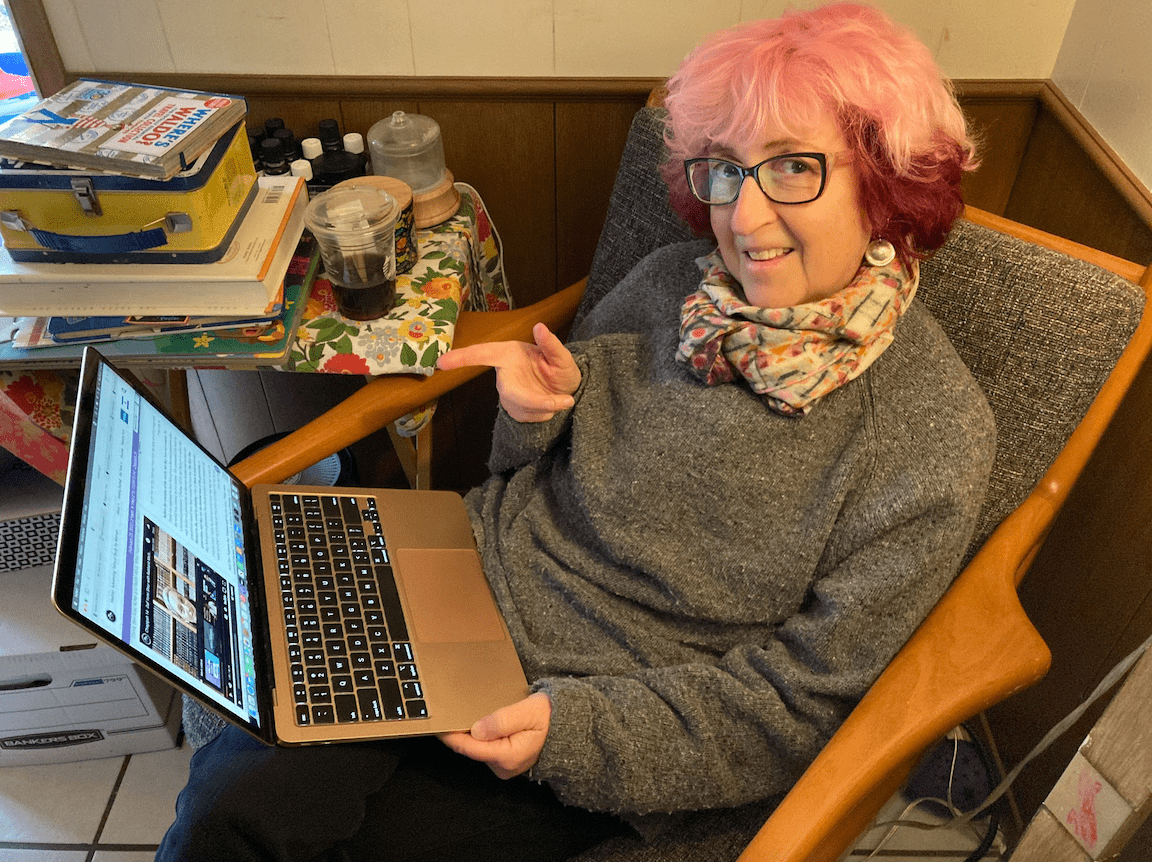

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Meilah 6

תָּא שְׁמַע, רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: יֵשׁ נוֹתָר שֶׁמּוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, וְיֵשׁ נוֹתָר שֶׁאֵין מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ.

The Gemara cites another source that might resolve the issue: Come and hear a baraita that can provide a proof with regard to the meaning of Rabbi Yehoshua’s statement about a period of fitness to the priests: Rabbi Shimon says that there is a case of notar, when the blood was left overnight and was rendered unfit, where one is liable for misusing the meat of the offering, and there is also a case of notar where one is not liable for misusing it.

כֵּיצַד? לָן לִפְנֵי זְרִיקָה – מוֹעֲלִין, לְאַחַר זְרִיקָה – אֵין מוֹעֲלִין.

The baraita elaborates: How so? If the blood was left over and someone consumed the meat before the sprinkling of the blood, he is liable for misusing consecrated property. But if it was consumed after the sprinkling of the blood, he is not liable for misusing consecrated property, as the sprinkling removes the meat from being subject to the halakhot of misuse.

קָתָנֵי מִיהַת: מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, לָאו דַּהֲוָה שְׁהוּת לְמִיזְרְקֵיהּ, דְּאִי בָּעֵי – זָרֵיק,

The Gemara notes: In any event, Rabbi Shimon teaches that if one consumes the meat before the leftover blood was sprinkled, he is liable for misusing it. Is this not referring to a case where there was time left in the day to sprinkle the blood that had already been collected in the service vessel, and therefore, if he had desired, he could have sprinkled the blood? Nevertheless, the offering is subject to the halakhot of misuse. This indicates that merely collecting the blood in the service vessel alone, without actually sprinkling it, does not remove the offering from being subject to the halakhot of misuse.

וּשְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: הֶיתֵּר אֲכִילָה שָׁנִינוּ!

And accordingly, one may conclude from the baraita that it is fitness of consuming the meat of the offering that we learned in Rabbi Yehoshua’s statement in the mishna. It is the fitness of consuming the meat of the offering that removes the possibility of being liable for the prohibition of misuse, not the fitness of sprinkling.

לָא, דְּקַבְּלֵיהּ סָמוּךְ לִשְׁקִיעַת הַחַמָּה, דְּלֹא הָיָה שְׁהוּת לְמִזְרַק.

The Gemara refutes this conclusion: No, the baraita is not referring to a case where there was time left in the day to sprinkle the blood that had already been collected. Rather, it is referring to a situation where the priest collected the blood shortly before sunset, where there was no time left in the day to sprinkle the blood while it was still daytime. Since the blood could not have been sprinkled, the offering is still subject to the prohibition of misuse. But if there had been time to sprinkle the blood, then that blood would be considered ready to be sprinkled, and the offering would no longer be subject to the prohibition of misuse, in accordance with the opinion that the criteria is the fitness of sprinkling of the blood.

אֲבָל הָיָה שְׁהוּת, מַאי? הָכִי נָמֵי דְּאֵין מוֹעֲלִין?

The Gemara raises a difficulty: But in that case, what is the halakha in a situation where there was time in the day to sprinkle the blood? According to the above claim, so too the halakha is that he is not liable for misusing the offering.

מַאי אִירְיָא דְּתָנֵי ״לִפְנֵי זְרִיקָה״, לִיתְנֵי ״קוֹדֶם שְׁקִיעָה״ וּ״לְאַחַר שְׁקִיעָה״!

If so, why does Rabbi Shimon specifically teach this distinction between a case before sprinkling, when the offering is still subject to the halakhot of misuse, and after sprinkling, when the offering is no longer subject to misuse? Let Rabbi Shimon instead teach a more precise distinction, between a situation where the blood was collected before sunset and there was time to sprinkle it but it was left overnight, in which case the offering is not subject to the prohibition of misuse, and a situation where the blood was collected after sunset, in which case it is still subject to the prohibition of misuse.

הָכִי נָמֵי קָתָנֵי: קוֹדֶם שֶׁיֵּרָאֶה לִזְרִיקָה, וּלְאַחַר שֶׁיֵּרָאֶה לִזְרִיקָה.

The Gemara answers that this is indeed what Rabbi Shimon meant, as he actually taught: Before it was fit for sprinkling, the offering is still subject to the prohibition of misuse, but after it was fit for sprinkling, it is no longer subject to the prohibition of misuse.

תָּא שְׁמַע, רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: יֵשׁ פִּיגּוּל שֶׁמּוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, וְיֵשׁ פִּיגּוּל שֶׁאֵין מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ.

The Gemara suggests another proof from a similar baraita. Come and hear: Rabbi Shimon says that there is a case of an offering of the most sacred order that was sacrificed with piggul intent where one is liable for misusing it, and there is also a case of piggul intent where one is not liable for misusing it.

כֵּיצַד? לִפְנֵי זְרִיקָה – מוֹעֲלִין, לְאַחַר זְרִיקָה – אֵין מוֹעֲלִין.

The baraita elaborates: How so? If someone consumed the meat before the sprinkling of the blood, he is liable for misusing consecrated property. If he consumed it after the sprinkling of the blood, he is not liable for misusing consecrated property, as the sprinkling removed the prohibition of misuse.

קָתָנֵי מִיהַת: לִפְנֵי זְרִיקָה – מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, לָאו דַּהֲוָה שְׁהוּת לְמִיזְרְקֵיהּ, דְּאִי בָּעֵי – זָרֵיק, וְקָתָנֵי ״מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ״, וּשְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: הֶיתֵּר אֲכִילָה שָׁנִינוּ!

In any event, Rabbi Shimon teaches that if one consumes the meat of an offering that was rendered piggul before the blood was sprinkled, he is liable for misusing it. Is this not referring to a case where there was time left in the day to sprinkle the blood that had already been collected in the service vessel, and therefore, if he had desired, he could have sprinkled the blood? And yet Rabbi Shimon teaches that one is liable for misusing it. Once again, this would indicate that merely collecting the blood in the service vessel alone, without sprinkling, does not remove the possibility of the prohibition of misuse. And accordingly, one may conclude from the baraita that it is fitness of consuming the meat of the offering that we learned in Rabbi Yehoshua’s statement in the mishna.

לָא, דְּלָא הֲוָה שְׁהוּת לְמִיזְרְקֵיהּ. אֲבָל הֲוָה שְׁהוּת לְמִיזְרְקֵיהּ, מַאי? הָכִי נָמֵי דִּנְפַק מִידֵי מְעִילָה?

The Gemara refutes this conclusion: No, the baraita is referring to a situation where the priest collected the blood shortly before sunset, where there was no time to sprinkle the blood while it was still daytime. Since the blood could not have been sprinkled, the offering is still subject to the prohibition of misuse. The Gemara raises a difficulty: But if so, what is the halakha in a case where there was time in the day to sprinkle the blood? According to the above claim, the offering is indeed removed from being subject to the halakhot of misuse.

מַאי אִירְיָא דְּתָנֵי ״לְאַחַר זְרִיקָה״, לִיתְנֵי ״קוֹדֶם שְׁקִיעָה״ וּ״לְאַחַר שְׁקִיעַת הַחַמָּה״!

If so, why does Rabbi Shimon specifically teach this distinction between after sprinkling, when the offering is no longer subject to the halakhot of misuse, and before sprinkling, when the offering is still subject to misuse? Let Rabbi Shimon instead teach a more precise distinction, between a situation where the blood was collected before sunset and there was time to sprinkle it but it was left overnight, in which case the offering is not subject to the prohibition of misuse, and a situation where the blood was collected after sunset, in which case it is still subject to the prohibition of misuse.

הָכִי נָמֵי קָאָמַר: קוֹדֶם שֶׁיֵּרָאֶה לִזְרִיקָה, לְאַחַר שֶׁיֵּרָאֶה לִזְרִיקָה.

The Gemara answers that that is indeed what Rabbi Shimon is saying: Before it was fit for sprinkling, the offering is still subject to the prohibition of misuse, but after it was fit for sprinkling, it is no longer subject to the prohibition of misuse.

תָּא שְׁמַע: הַפִּיגּוּל בְּקׇדְשֵׁי קָדָשִׁים – מוֹעֲלִין. מַאי לָאו דְּזָרַק, וּשְׁמַע מִינַּהּ: הֶיתֵּר אֲכִילָה שָׁנִינוּ! לָא, דְּלֹא זָרַק.

§ The Gemara suggests another proof. Come and hear: An offering of the most sacred order which is piggul is subject to the halakhot of misuse. The Gemara analyzes this statement: What, is this baraita not referring to a case where the priest already sprinkled its blood? This would indicate that a fit offering, unlike a piggul offering, is no longer subject to the prohibition of misuse only once the blood is sprinkled. And if so, one may conclude from the baraita that it is fitness of consuming the meat of the offering that we learned in Rabbi Yehoshua’s statement in the mishna, i.e., this fitness of consuming the meat of the offering removes the prohibition of misuse. The Gemara rejects this suggestion: No, one cannot cite a proof from this baraita, as it is possible that the baraita is referring to a case where the priest did not yet sprinkle the blood.

אֲבָל זָרַק מַאי? הָכִי נָמֵי דְּאֵין מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ? מַאי אִירְיָא דְּתָנֵי בְּקָדָשִׁים קַלִּים אֵין מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ,

The Gemara asks: But if so, what, then, is the halakha in a case where the priest did sprinkle the blood? Is the halakha indeed that one is no longer liable for misusing it? If so, why does the latter clause of the baraita specifically teach: Unlike an offering of the most sacred order, in the case of the sacrificial portions of an offering of lesser sanctity one is not liable for misusing it?

לִיתְנֵי: כָּאן – לִפְנֵי זְרִיקָה, כָּאן – לְאַחַר זְרִיקָה!

Let the baraita instead teach a distinction within the category of offerings of the most sacred order themselves: Here, the offering is subject to the prohibition of misuse because it is before the sprinkling of the blood, and there, the offering is not subject to the prohibition of misuse because it is after the sprinkling of the blood.

הָא אָתְיָא לְאַשְׁמוֹעִינַן: כֹּל לְאֵיתוֹיֵי לִידֵי מְעִילָה, זְרִיקָה כְּתִיקְנָהּ מַיְיתֵי לִידֵי מְעִילָה.

The Gemara answers: The baraita could have taught that distinction, but it chose to state a distinction between offerings of the most sacred order and offerings of lesser sanctity because it comes to teach us this following principle: In any case where the result of sprinkling brings the offering into the category of the halakhot of misuse, e.g., the sacrificial portions of offerings of lesser sanctity, to which the halakhot of misuse apply only after the blood had been sprinkled, only sprinkling the blood properly brings the offering into the halakhot of misuse.

כֹּל לְאַפּוֹקֵי מִידֵי מְעִילָה, אֲפִילּוּ שֶׁלֹּא כְּתִיקְנָהּ נָמֵי מַפְקַע מִידֵי מְעִילָה.

By contrast, in any situation where the result of sprinkling is removing the offering from the halakhot of misuse, e.g., the meat of an offering of the most sacred order, which was subject to the halakhot of misuse even before the blood was sprinkled, even sprinkling the blood improperly removes the offering from the halakhot of misuse. This ruling is not in accordance with the opinion of Rav Giddel.

מַתְנִי׳ בְּשַׂר קׇדְשֵׁי קָדָשִׁים שֶׁיָּצָא לִפְנֵי זְרִיקַת דָּמִים,

MISHNA: The mishna presents a dispute with regard to the status of offerings of the most sacred order, which normally are not subject to the halakhot of misuse once their blood has been sprinkled and they have been permitted to the priests. The case of the mishna is the meat of offerings of the most sacred order, whose consumption is permitted from the moment their blood was sprinkled, that left the Temple courtyard before the sprinkling of the blood, and then reentered the courtyard.

רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, וְאֵין חַיָּיבִין עָלָיו מִשּׁוּם פִּיגּוּל וְנוֹתָר וְטָמֵא.

Rabbi Eliezer says: The sprinkling of this blood does not permit its consumption by the priests. Consequently, one is liable for misusing it. And he is not liable for eating it due to violation of the prohibitions of piggul, if he partook of it after it was slaughtered with the intent to partake of it or sprinkle its blood beyond its designated time, or of notar, if he partook of the meat after it remained overnight, or of partaking of the meat while ritually impure.

רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: אֵין מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, וְחַיָּיבִין עָלָיו מִשּׁוּם פִּיגּוּל וְנוֹתָר וְטָמֵא.

Rabbi Akiva says: The sprinkling is effective despite the fact that the meat left the Temple courtyard and was disqualified, and therefore one is not liable for misusing it. Likewise, other halakhot that apply to offerings whose blood was sprinkled apply to it, and consequently one is liable for eating it due to violation of the prohibitions of partaking of meat that is piggul, or notar, or remained overnight, or of partaking of the meat while ritually impure.

אָמַר רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא: וַהֲרֵי הַמַּפְרִישׁ חַטָּאתוֹ וְאָבְדָה, וְהִפְרִישׁ אַחֶרֶת תַּחְתֶּיהָ, וְאַחַר כָּךְ נִמְצֵאת הָרִאשׁוֹנָה, וַהֲרֵי שְׁתֵּיהֶן עוֹמְדוֹת.

Rabbi Akiva said, in support of his opinion: But there is the case of one who designated an animal as his sin offering and it was lost, and he designated another animal in its stead, and thereafter the first sin offering was found and both of them are standing fit for sacrifice. If he slaughtered both animals at the same time and sprinkled the blood of one of them, which means that the second was disqualified as a leftover sin offering, the question arises as to the status of the meat of the second animal with regard to the halakhot of misuse.

לֹא כְּשֵׁם שֶׁדָּמָהּ פּוֹטֵר אֶת בְּשָׂרָהּ, כָּךְ הוּא פּוֹטֵר אֶת בְּשַׂר חֲבֶרְתָּהּ?

Is it not the case that just as the blood of the animal whose blood was sprinkled exempts its meat from liability for its misuse, so too it exempts the meat of the other animal? Since he could have chosen to sprinkle the blood of either animal, they are considered as though they were one offering.

אִם פָּטַר דָּמָהּ אֶת בְּשַׂר חֲבֶרְתָּהּ מִן הַמְּעִילָה, דִּין הוּא שֶׁיִּפְטֹר אֶת בְּשַׂר עַצְמָהּ!

If so, one may learn from there by an a fortiori inference with regard to the case of sprinkling the blood of meat that left the courtyard and returned: If the sprinkling of its blood exempted the meat of the other animal from the halakhot of misuse, it is only right that it should exempt its own meat that left the courtyard.

אֵימוּרַי קָדָשִׁים קַלִּים שֶׁיָּצְאוּ לִפְנֵי זְרִיקַת דָּמִים,

The mishna adds that just as Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Akiva disagree as to whether the sprinkling of blood exempts meat that left the courtyard from liability for its misuse, so too, they disagree with regard to the sacrificial portions of offerings of lesser sanctity consumed on the altar that left the Temple courtyard before the sprinkling of the blood. The dispute is whether the subsequent sprinkling of the blood generates liability for misuse of those portions.

רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: אֵין מוֹעֲלִין בָּהֶן, וְאֵין חַיָּיבִין עֲלֵיהֶן מִשּׁוּם פִּיגּוּל נוֹתָר וְטָמֵא. רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמֵר: מוֹעֲלִין בָּהֶן, וְחַיָּיבִין עֲלֵיהֶן מִשּׁוּם פִּיגּוּל נוֹתָר וְטָמֵא.

Rabbi Eliezer says: The sprinkling of the blood is completely ineffective in rendering those portions consecrated to the Lord. Consequently, one is not liable for misusing them. And similarly, one is not liable for their consumption due to violation of the prohibitions of piggul, notar, or of partaking of meat while ritually impure. Rabbi Akiva says: The sprinkling is effective, and therefore one is liable for misusing them. And likewise, one is liable for its consumption due to violation of the prohibitions of piggul, notar, or of partaking of the meat while ritually impure.

גְּמָ׳ וְהָנֵי תַּרְתֵּי לְמָה לִי?

GEMARA: The Gemara asks: Why do I need the mishna to cite these two disagreements, i.e., both the case of offerings of the most sacred order and offerings of lesser sanctity? After all, both disagreements are based on the same principle.

צְרִיכִי, דְּאִי אִיתְּמַר בְּקׇדְשֵׁי קָדָשִׁים, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: בְּהָא קָא אָמַר רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר מוֹעֲלִין בּוֹ, מִשּׁוּם דִּזְרִיקָה כְּתִיקְנָהּ מַפְּקָא מִידֵי מְעִילָה, שֶׁלֹּא כְּתִיקְנָהּ – לָא מַפְּקָא מִידֵי מְעִילָה.

The Gemara answers: Both cases are necessary, as, if the disagreement was stated only with regard to offerings of the most sacred order, I would say that it is specifically in that case that Rabbi Eliezer says that one is liable for misusing the meat of the offering, due to the fact that only sprinkling the blood properly removes the offering from being subject to the halakhot of misuse. By contrast, sprinkling the blood improperly, including for meat that left the courtyard, does not remove the offering from the halakhot of misuse.

אֲבָל לְאֵיתוֹיֵי לִידֵי מְעִילָה – מוֹדֵי לְרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא דַּאֲפִילּוּ שֶׁלֹּא כְּתִיקְנָהּ מַיְיתָא לִידֵי מְעִילָה,

But with regard to the issue of when the rite of sprinkling brings the offering into being subject to the halakhot of misuse, i.e., in the case of sacrificial portions of offerings of lesser sanctity, Rabbi Eliezer concedes to Rabbi Akiva that even sprinkling the blood improperly, as in this case, brings the offering into being subject to the halakhot of misuse.

וְאִי אִיתְּמַר גַּבֵּי קָדָשִׁים קַלִּים, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: גַּבֵּי קָדָשִׁים קַלִּים הוּא דְּאָמַר רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא מוֹעֲלִין בָּהֶן, דַּאֲפִילּוּ זְרִיקָה שֶׁלֹּא כְּתִיקְנָהּ מַיְיתָא לִידֵי מְעִילָה,

And by contrast, if their disagreement was stated only with regard to offerings of lesser sanctity, I would say that it is specifically in the case of offerings of lesser sanctity that Rabbi Akiva said one is liable for misusing them. This is due to the fact that here the act of sprinkling serves to include them in the category of misuse, and therefore even sprinkling the blood improperly, as in this case, brings the offering into being subject to the halakhot of misuse.

אֲבָל קׇדְשֵׁי קָדָשִׁים, דִּלְאַפּוֹקֵי הוּא, שֶׁלֹּא כְּתִיקְנָהּ – לָא מַפְּקָא מִידֵי מְעִילָה, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

But with regard to offerings of the most sacred order, where the sprinkling of the blood serves to remove the offering from being subject to the halakhot of misuse, one might say that Rabbi Akiva agrees that sprinkling the blood improperly does not remove the offering from being subject to the halakhot of misuse. Therefore, the mishna teaches us that the tanna’im disagree in both cases.

אִתְּמַר, אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: כִּי אָמַר רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא זְרִיקָה מוֹעֶלֶת לַיּוֹצֵא – שֶׁיָּצָא מִקְצָתוֹ, אֲבָל יוֹצֵא כּוּלּוֹ – לֹא אָמַר רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא.

§ It was stated that amora’im disagree with regard to the opinion of Rabbi Akiva in the mishna. Rabbi Yoḥanan says: When Rabbi Akiva says that sprinkling is effective to remove the meat of offerings of the most sacred order that left the courtyard from the halakhot of misuse, that applies specifically in a case where only part of it left the courtyard and part remained inside. In such a situation, as the sprinkling is effective for the portion that remained inside the courtyard, it also is effective for the portion that left the courtyard. But if all of it left the courtyard, Rabbi Akiva did not say that the sprinkling is effective to remove the meat from the halakhot of misuse.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב אַסִּי לְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: כְּבָר לִימְּדוּנִי חֲבֵירַי שֶׁבַּגּוֹלָה

Rav Asi said to Rabbi Yoḥanan: My colleagues in the exile, i.e., the Sages of Babylonia, already taught me that