Study Guide Menachot 13. The mishna seems to contradict the previous mishna as it implies that the remainder can become pigul if one had thoughts of eating half a shiur of the remainder tomorrow and half a shiur of the kometz tomorrow, even though the kometz can’t be eaten. Two answers are offered. Can a pigul thought about the frankincense during the act of kemitza create pigul that one would be obligated in karet? Since the frankincense is not the same object as the meal offering, even though they go together, do we view these as one unit or not? Rabbi Yossi says there is no karet. Reish Lakish explains the logic behind his argument although questions are raised regarding his explanation. Is collecting the frankincense from the meal offering mixture considered a sacrificial rite such that it would be forbidden by a non Kohen?

Menachot 13

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

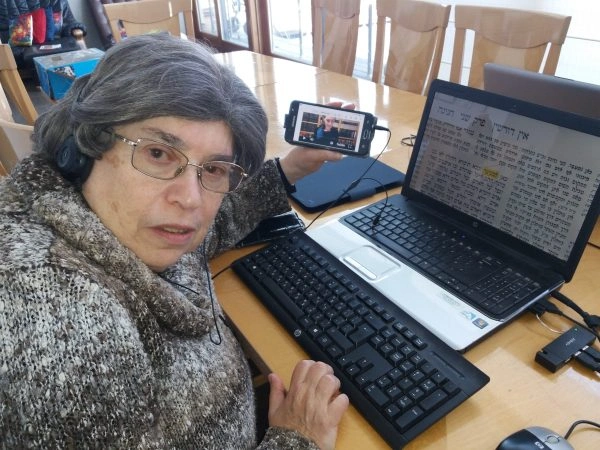

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Menachot 13

הָא תּוּ לְמָה לִי? אִי לֶאֱכוֹל וְלֶאֱכוֹל דָּבָר (שאין) [שֶׁ]דַּרְכּוֹ לֶאֱכוֹל קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן דְּמִצְטָרֵף, מֵרֵישָׁא דְּסֵיפָא שָׁמְעַתְּ מִינַּהּ, דְּקָתָנֵי: כַּחֲצִי זַיִת בַּחוּץ כַּחֲצִי זַיִת לְמָחָר פָּסוּל, הָא כַּחֲצִי זַיִת לְמָחָר וְכַחֲצִי זַיִת לְמָחָר – פִּיגּוּל.

According to Abaye, why do I also need this mishna here? If you will suggest that this mishna is necessary, as one can infer from it that if one intended to partake of half an olive-bulk the next day and then intended to partake of another half an olive-bulk the next day, both from an item whose typical manner is such that one partakes of it, the mishna teaches us that they join together in order to render the offering piggul, this suggestion can be rejected: But you already learn the halakha in this case from the first clause of the latter clause of the previous mishna, as it teaches: Half an olive-bulk outside and half an olive-bulk the next day, the offering is unfit. One can infer from this that if his intent was to consume half an olive-bulk the next day and half an olive-bulk the next day, it is piggul.

אִי לֶאֱכוֹל וּלְהַקְטִיר (דְּהִיא גּוּפַהּ קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן), מִדִּיּוּקָא דְּרֵישָׁא שָׁמְעַתְּ מִינַּהּ.

If you suggest that the mishna is necessary for a case where one intended to consume and to burn, i.e., that the mishna teaches us the matter itself, that intent to consume does not join together with intent to burn, this too cannot be. The reason is that from the inference of the first clause of the mishna you can already learn the halakha in this case, as it teaches: If one intended to partake of an item whose typical manner is such that one partakes of it, the offering is rendered piggul. This indicates that if his intent was to consume an item whose typical manner is such that one does not consume it, the offering is not rendered piggul.

דְּהַשְׁתָּא, מָה לֶאֱכוֹל וְלֶאֱכוֹל דָּבָר שֶׁאֵין דַּרְכּוֹ לֶאֱכוֹל – אָמְרַתְּ לָא מִצְטָרֵף, לֶאֱכוֹל וּלְהַקְטִיר מִיבַּעְיָא?

The Gemara explains how the halakha that intent to consume and burn do not combine can be inferred from the mishna: Now consider, if when one intended to partake of an item whose typical manner is such that one partakes of it and to partake of an item whose typical manner is such that one does not partake of it, you say that his intentions do not join together, despite the fact that both of his intentions referred to consumption, is it necessary for the mishna to teach that intentions to consume and to burn do not join together?

אִין, לֶאֱכוֹל וּלְהַקְטִיר אִיצְטְרִיכָא לֵיהּ, סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ אָמֵינָא: הָתָם הוּא דְּלָא כִּי אוֹרְחֵיהּ קָמְחַשֵּׁב.

The Gemara responds: Yes; although the mishna teaches the halakha of a case where one intended to consume an item typically consumed and to consume an item typically not consumed, it was necessary for the mishna to teach the halakha of a case where one intended to eat and to burn. As it might enter your mind to say that there, where one’s intentions referred solely to consumption, the halakha is that his intentions do not join together, as he intended to act not in accordance with its typical manner, since he intended to consume that which is not meant to be consumed.

אֲבָל הָכָא, דִּבְהַאי כִּי אוֹרְחֵיהּ קָמְחַשֵּׁב, וּבְהַאי כִּי אוֹרְחֵיהּ קָא מְחַשֵּׁב, אֵימָא לִצְטָרֵף, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara continues: But here, where his intent was to consume half an olive-bulk and to burn half an olive-bulk, where with regard to this half he intends in accordance with its typical manner, and with regard to this half he intends in accordance with its typical manner, one might say that they should join together, despite the fact that each intention concerns only half an olive-bulk. Therefore, the mishna teaches us that such intentions do not join together, and the mishna can be explained even in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis.

הֲדַרַן עֲלָךְ כׇּל הַמְּנָחוֹת.

מַתְנִי׳ הַקּוֹמֵץ אֶת הַמִּנְחָה לֶאֱכוֹל שְׁיָרֶיהָ אוֹ לְהַקְטִיר קוּמְצָהּ לְמָחָר – מוֹדֶה רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בָּזֶה שֶׁהוּא פִּיגּוּל וְחַיָּיבִין עָלָיו כָּרֵת. לְהַקְטִיר לְבוֹנָתָהּ לְמָחָר, רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: פָּסוּל וְאֵין בּוֹ כָּרֵת, וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: פִּיגּוּל וְחַיָּיבִין עָלָיו כָּרֵת.

MISHNA: In the case of a priest who removes a handful from the meal offering with the intent to partake of its remainder or to burn its handful on the next day, Rabbi Yosei concedes in this instance that it is a case of piggul and he is liable to receive karet for partaking of it. But if the priest’s intent was to burn its frankincense the next day, Rabbi Yosei says: The meal offering is unfit but partaking of it does not include liability to receive karet. And the Rabbis say: It is a case of piggul and he is liable to receive karet for partaking of the meal offering.

אָמְרוּ לוֹ: מָה (שִׁינָּה) [שָׁנַת] זוֹ מִן הַזֶּבַח? אָמַר לָהֶן: שֶׁהַזֶּבַח דָּמוֹ וּבְשָׂרוֹ וְאֵימוּרָיו אֶחָד, וּלְבוֹנָה אֵינָהּ מִן הַמִּנְחָה.

The Rabbis said to Rabbi Yosei: In what manner does this differ from an animal offering, where if one slaughtered it with the intent to sacrifice the portions consumed on the altar the next day, it is piggul? Rabbi Yosei said to the Rabbis: There is a difference, as in the case of an animal offering, its blood, and its flesh, and its portions consumed on the altar are all one entity. Consequently, intent with regard to any one of them renders the entire offering piggul. But the frankincense is not part of the meal offering.

גְּמָ׳ לְמָה לִי לְמִיתְנֵא ״מוֹדֶה רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בָּזוֹ״?

GEMARA: The Gemara questions the terminology of the mishna: Why do I need the tanna to teach that Rabbi Yosei concedes in this instance? Let the tanna simply state: If one removes the handful from a meal offering with the intent to partake of its remainder or to burn the handful on the next day, Rabbi Yosei says that the offering is piggul and one is liable to receive karet for partaking of the remainder.

מִשּׁוּם דְּקָא בָּעֵי לְמִיתְנֵא סֵיפָא, לְהַקְטִיר לְבוֹנָתָהּ לְמָחָר, רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: פָּסוּל וְאֵין בּוֹ כָּרֵת.

The Gemara responds: It was necessary for the tanna to teach that Rabbi Yosei concedes, because he wants to teach the latter clause of the mishna, that if his intent was to burn its frankincense the next day, Rabbi Yosei says that the meal offering is unfit, but partaking of it does not include liability to receive karet.

מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא: טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי מִשּׁוּם דְּקָסָבַר אֵין מְפַגְּלִין בַּחֲצִי מַתִּיר, וַאֲפִילּוּ רֵישָׁא נָמֵי,

The Gemara elaborates: The reason the tanna links the two cases of the mishna is lest you say that the reason that Rabbi Yosei does not render the meal offering piggul is because he holds that one cannot render an offering piggul with intent that concerns only half of its permitting factors. And consequently, since the burning of the handful and the frankincense render the remainder of a meal offering permitted for consumption, then even in the first clause of the mishna, where one intends to burn the handful the next day, Rabbi Yosei should hold that the offering is not rendered piggul, as the intent does not refer to the frankincense as well.

קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן דִּבְהָא מוֹדֵי.

Therefore, the tanna teaches us that in this case Rabbi Yosei concedes that if the handful is removed with the intent to burn only the handful on the next day, the offering is rendered piggul. Accordingly, Rabbi Yosei holds that one renders an offering piggul with intent that concerns only half of its permitting factors, and the offering is not rendered piggul in the case of the latter clause for a different reason, as the Gemara will discuss later.

לְהַקְטִיר לְבוֹנָתָהּ לְמָחָר, רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: פָּסוּל וְאֵין בּוֹ כָּרֵת. אָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: אוֹמֵר הָיָה רַבִּי יוֹסֵי, אֵין מַתִּיר מְפַגֵּל אֶת הַמַּתִּיר.

§ The mishna teaches that if one removed the handful from a meal offering with the intent to burn its frankincense on the next day, Rabbi Yosei says that the meal offering is unfit but partaking of it does not include liability to receive karet. Concerning this, Reish Lakish says: Rabbi Yosei would say, i.e., this is Rabbi Yosei’s reasoning: A permitting factor does not render another permitting factor piggul. In other words, if, while performing the rites of a permitting factor, one had intent to perform the rites of a different permitting factor outside its designated time, the offering is not rendered piggul on account of this intent.

וְכֵן אַתָּה אוֹמֵר בִּשְׁנֵי בְּזִיכֵי לְבוֹנָה שֶׁל לֶחֶם הַפָּנִים, שֶׁאֵין מַתִּיר מְפַגֵּל אֶת הַמַּתִּיר.

Reish Lakish adds: And you would say the same with regard to the two bowls of frankincense of the shewbread, that a permitting factor does not render another permitting factor piggul, and therefore if the priest burned one of the bowls with the intent to burn the other bowl the next day, the shewbread is not rendered piggul.

מַאי ״וְכֵן אַתָּה אוֹמֵר״? מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בִּלְבוֹנָה – מִשּׁוּם דְּלָאו מִינַהּ דְּמִנְחָה הִיא, אֲבָל בִּשְׁנֵי בְּזִיכֵי לְבוֹנָה, דְּמִינַהּ דַּהֲדָדֵי נִינְהוּ – אֵימָא מְפַגְּלִי אַהֲדָדֵי, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara asks: What is the purpose of the apparently superfluous statement: And you would say the same with regard to the two bowls of frankincense? Is there reason to assume that Rabbi Yosei would hold that the shewbread is rendered piggul in such a case? The Gemara responds that it is necessary, lest you say that the reason that Rabbi Yosei holds that there is no piggul in the case of the frankincense is because it is not of the same type as a meal offering. But with regard to the two bowls of frankincense, which are of the same type as each other, one might say that they do render one another piggul. Therefore, Reish Lakish teaches us that in both instances one permitting factor does not render another permitting factor piggul.

וּמִי מָצֵית אָמְרַתְּ טַעְמָא דְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בִּלְבוֹנָה לָאו מִשּׁוּם דְּלָאו מִינַהּ דְּמִנְחָה הִיא? וְהָא קָתָנֵי סֵיפָא: אָמְרוּ לוֹ: מָה שִׁינְּתָה מִן הַזֶּבַח? אָמַר לָהֶן: הַזֶּבַח דָּמוֹ וּבְשָׂרוֹ וְאֵימוּרָיו אֶחָד, וּלְבוֹנָה אֵינָהּ מִן הַמִּנְחָה.

The Gemara asks: And can you say that the reason for the opinion of Rabbi Yosei in the case of the frankincense in the mishna is not due to the fact that the frankincense is not of the same type as a meal offering? But isn’t it taught in the latter clause of the mishna that the Rabbis said to Rabbi Yosei: In what manner does the frankincense differ from an animal offering, where if one slaughtered it with the intent to sacrifice the portions consumed on the altar the next day it is piggul; and Rabbi Yosei said to the Rabbis: There is a difference, as in the case of an animal offering, its blood, and its flesh, and its portions consumed on the altar are all one entity, but the frankincense is not part of the meal offering? The mishna indicates that according to Rabbi Yosei the reason the meal offering is not piggul is because the frankincense is not of the same type as the meal offering.

מַאי ״אֵינָהּ מִן הַמִּנְחָה״? אֵינָהּ בְּעִיכּוּב מִנְחָה, דְּלָאו כִּי הֵיכִי דִּמְעַכֵּב לְהוּ קוֹמֶץ לְשִׁירַיִם, דְּכַמָּה דְּלָאו מִתְקַטַּר קוֹמֶץ לָא מִיתְאַכְלִי שִׁירַיִם, הָכִי נָמֵי מְעַכֵּב לַהּ לִלְבוֹנָה, אֶלָּא אִי בָּעֵי הַאי מַקְטַר בְּרֵישָׁא וְאִי בָּעֵי הַאי מַקְטַר בְּרֵישָׁא.

The Gemara explains: What does Rabbi Yosei mean when he says that the frankincense is not part of the meal offering? He means that it is not part of the preclusion of the meal offering. The Gemara elaborates: This means that the halakha is not that just as the handful precludes the remainder, i.e., that as long as the handful is not burned the remainder may not be consumed, so too the handful precludes the frankincense from being burned upon the altar. Rather, if the priest wants, he burns this first, and if he wants, he burns that first, i.e., he may burn the frankincense before or after the burning of the handful. Accordingly, the frankincense is an independent permitting factor. For this reason, intent with regard to the frankincense that occurred during the removal of the handful does not render a meal offering piggul.

וְרַבָּנַן, כִּי אָמְרִינַן ״אֵין מַתִּיר מְפַגֵּל אֶת הַמַּתִּיר״ (גַּבֵּי שָׁחַט אֶחָד מִן הַכְּבָשִׂים לֶאֱכוֹל מֵחֲבֵירוֹ לְמָחָר, דְּאָמְרַתְּ שְׁנֵיהֶם כְּשֵׁרִים), הָנֵי מִילֵּי הֵיכָא דְּלָא אִיקְּבַעוּ בְּחַד מָנָא, אֲבָל הֵיכָא דְּאִיקְּבַעוּ בְּחַד מָנָא – כְּחַד דָּמֵי.

The Gemara asks: And the Rabbis, who say that the meal offering is rendered piggul in such a case, what is their opinion? The Gemara responds: They hold that when we say that a permitting factor does not render another permitting factor piggul, this is with regard to the case taught in a mishna (16a) concerning one who slaughtered one of the lambs whose sacrifice permits the consumption of the two loaves meal offering brought on Shavuot, with the intent to partake of the other lamb the next day. The Gemara elaborates: When you said in the mishna that both permitting factors are fit, this statement applies only where they were not fixed in one vessel. But in a situation where they were fixed in one vessel, as is the case with regard to the handful and the frankincense, they are considered like one unit, and therefore they render one another piggul.

אָמַר רַבִּי יַנַּאי: לִיקּוּט לְבוֹנָה בְּזָר – פָּסוּל. מַאי טַעְמָא? אָמַר רַבִּי יִרְמְיָה: מִשּׁוּם הוֹלָכָה נָגְעוּ בָּהּ, קָסָבַר הוֹלָכָה שֶׁלֹּא בָּרֶגֶל שְׁמָהּ הוֹלָכָה, וְהוֹלָכָה בְּזָר – פְּסוּלָה.

§ With regard to the frankincense, Rabbi Yannai says: The collection of the frankincense from a meal offering, when performed by a non-priest, is not valid and disqualifies the meal offering. The Gemara asks: What is the reason? Rabbi Yirmeya said: It is because the rite of conveying has touched it, i.e., the collection of the frankincense is considered part of the rite of the conveying of the frankincense to the altar for the purpose of burning. Even if the non-priest simply collected the frankincense and thereafter transferred it to a priest, Rabbi Yannai holds that conveying even without moving one’s leg is called conveying, and the halakha is that the performance of the rite of conveying by a non-priest is not valid.

אָמַר רַב מָרִי: אַף אֲנַן נָמֵי תְּנֵינָא, זֶה הַכְּלָל: כׇּל הַקּוֹמֵץ, וְנוֹתֵן בִּכְלִי, וְהַמּוֹלִיךְ, וְהַמַּקְטִיר.

Rav Mari said: We learn this halakha in the mishna on 12a, which discusses those sacrificial rites of a meal offering during which improper intent renders an offering piggul, as well. The mishna teaches: This is the principle: In the case of anyone who removes the handful, or places the handful in the vessel, or who conveys the vessel with the handful to the altar, or who burns the handful on the altar, with the intent to partake of an item whose typical manner is such that one partakes of it, or to burn an item whose typical manner is such that one burns it on the altar, outside its designated area, the meal offering is unfit but there is no liability for karet. If his intent was to perform any of these actions beyond their designated time, the offering is piggul and one is liable to receive karet on account of it, provided that the permitting factor, i.e., the handful, was sacrificed in accordance with its mitzva.

בִּשְׁלָמָא קוֹמֵץ הַיְינוּ שׁוֹחֵט, מוֹלִיךְ נָמֵי הַיְינוּ מוֹלִיךְ, מַקְטִיר הַיְינוּ זוֹרֵק, אֶלָּא נוֹתֵן בִּכְלִי מַאי קָא עָבֵיד?

Rav Mari analyzes the first part of this mishna: Granted, the removal of the handful from a meal offering is the same as, i.e., equivalent to, the slaughter of animal offerings. The conveying of the handful to the altar in order to burn it is also the same as the conveying of the blood of a slaughtered offering to the altar in order to sprinkle it. Similarly, the burning of the handful and frankincense of a meal offering is comparable to the sprinkling of the blood of a slaughtered offering upon the altar. But as for placing the handful in the service vessel, what rite is he performing that is comparable to a rite of slaughtered offerings?

אִילֵּימָא מִשּׁוּם דְּדָמֵי לְקַבָּלָה, מִי דָּמֵי? הָתָם מִמֵּילָא, הָכָא קָא שָׁקֵיל וְרָמֵי.

If we say that the meal offering is piggul because the placing of the handful into a vessel is comparable to the collection of the blood of a slaughtered offering into a service vessel, one can ask: Are these rites in fact comparable? There, in the case of animal offerings, the blood enters the vessel by itself, whereas here, the priest takes the handful from the meal offering and casts it into the vessel.

אֶלָּא מִשּׁוּם דְּכֵיוָן דְּלָא סַגִּיא לֵיהּ דְּלָא עָבֵד לַהּ, עֲבוֹדָה חֲשׁוּבָה הִיא, עַל כֻּרְחָיךְ מְשַׁוֵּי לַהּ כְּקַבָּלָה. הָכָא נָמֵי, כֵּיוָן דְּלָא סַגִּיא לֵהּ דְּלָא עָבֵד לַהּ, עֲבוֹדָה חֲשׁוּבָה הִיא, עַל כֻּרְחָיךְ מְשַׁוֵּי לַהּ כִּי הוֹלָכָה.

Rather, it must be due to the following reason: Since it is not possible to sacrifice the handful without first performing the act of placing it in a vessel, the placement of the handful in a vessel is considered a significant rite, and perforce this factor causes it to be considered like the collection of the blood. Here too, with regard to the collection of the frankincense, since it is not possible to sacrifice the frankincense without first performing the act of collecting it from the vessel, the collection of the frankincense is a significant rite that perforce causes it to be considered like the rite of conveying.

לָא, לְעוֹלָם דְּדָמֵי לְקַבָּלָה, וּדְקָא קַשְׁיָא לָךְ: הָתָם מִמֵּילָא, הָכָא קָא שָׁקֵיל וְרָמֵי –

The Gemara rejects this suggestion: No, this is not the reason, and one cannot prove from the mishna that the collection of the frankincense from a meal offering performed by a non-priest is not valid. Actually, the reason why intent during the placement of the handful renders the offering piggul is in fact because it is comparable to the collection of the blood of a slaughtered offering. And as for the difficulty you raised, that there the blood enters the vessel by itself, whereas here he takes the handful from the meal offering and casts it into the vessel, this is not a true difficulty.

מִכְּדֵי תַּרְוַיְיהוּ קְדוּשַּׁת כְּלִי הוּא, מָה לִי מִמֵּילָא, מָה לִי קָא שָׁקֵיל וְרָמֵי.

The Gemara explains: Now consider, both of them, i.e., the collection of the blood and the placing of the handful, involve the sanctity of a vessel, in which a service vessel sanctifies a permitting factor to the altar, either the handful or the blood. What difference is it to me if the permitting factor enters the vessel by itself or whether one takes the item and casts it into the vessel?

מַתְנִי׳ שָׁחַט שְׁנֵי כְּבָשִׂים לֶאֱכוֹל אַחַת מִן הַחַלּוֹת לְמָחָר, הִקְטִיר שְׁנֵי בָּזִיכִין לֶאֱכוֹל אֶחָד מִן הַסְּדָרִים לְמָחָר, רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: אוֹתָהּ הַחַלָּה וְאוֹתוֹ הַסֵּדֶר שֶׁחִישֵּׁב עָלָיו – פִּיגּוּל וְחַיָּיבִין עָלָיו כָּרֵת, וְהַשֵּׁנִי פָּסוּל וְאֵין בּוֹ כָּרֵת. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: זֶה וָזֶה פִּיגּוּל וְחַיָּיבִין עָלָיו כָּרֵת.

MISHNA: If one slaughtered the two lambs that accompany the two meal offering loaves sacrificed on Shavuot with the intent to partake of one of the two loaves the next day, or if one burned the two bowls of frankincense accompanying the shewbread with the intent to partake of one of the arrangements of the shewbread the next day, Rabbi Yosei says: That loaf and that arrangement of which he intended to partake the next day are piggul and one is liable to receive karet for their consumption, and the second loaf and arrangement are unfit, but there is no liability to receive karet for their consumption. And the Rabbis say: This loaf and arrangement and that loaf and arrangement are both piggul and one is liable to receive karet for their consumption.

גְּמָ׳ אָמַר רַב הוּנָא: אוֹמֵר הָיָה רַבִּי יוֹסֵי, פִּיגֵּל בַּיָּרֵךְ שֶׁל יָמִין – לֹא נִתְפַּגֵּל הַיָּרֵךְ שֶׁל שְׂמֹאל. מַאי טַעְמָא? אִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא סְבָרָא, וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא קְרָא.

GEMARA: Rav Huna says: Rabbi Yosei would say, in accordance with his opinion that intent of piggul with regard to one loaf or one arrangement does not render the second loaf or arrangement piggul, that if one had intent of piggul with regard to the right thigh, i.e., he slaughtered an offering with the intent to partake of the right thigh the next day, then the left thigh has not become piggul and one is not liable to receive karet for its consumption. What is the reason for this? If you wish, propose a logical argument, and if you wish, cite a verse.

אִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא סְבָרָא: לָא עֲדִיפָא מַחְשָׁבָה מִמַּעֲשֵׂה הַטּוּמְאָה, אִילּוּ אִיטַּמִּי חַד אֵבֶר מִי אִיטַּמִּי לֵיהּ כּוּלֵּיהּ? וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא קְרָא: ״וְהַנֶּפֶשׁ הָאֹכֶלֶת מִמֶּנּוּ עֲוֹנָהּ תִּשָּׂא״ – מִמֶּנּוּ וְלֹא מֵחֲבֵירוֹ.

Rav Huna elaborates: If you wish, propose a logical argument: Disqualifying intent is no stronger than an incident of ritual impurity, and if one limb of an offering became impure, did the entire offering then become impure? Accordingly, one limb can be rendered piggul without the other. And if you wish, cite a verse that addresses piggul: “And the soul that eats of it shall bear his iniquity” (Leviticus 7:18). The verse indicates that one who eats specifically “of it,” i.e., from one part, shall bear his iniquity, and not one who eats from the other part of the offering.

אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רַב נַחְמָן לְרַב הוּנָא: וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים, לְעוֹלָם אֵין בּוֹ כָּרֵת עַד שֶׁיְּפַגֵּל בִּשְׁתֵּיהֶן בִּכְזַיִת. בִּשְׁתֵּיהֶן – אִין, בְּאַחַת מֵהֶן – לָא.

Rav Naḥman raised an objection to Rav Huna from a baraita: And the Rabbis say that there is never liability to receive karet for partaking of the two loaves unless one has intent of piggul with regard to an olive-bulk of both of them, i.e., one’s intent renders both loaves piggul only if he slaughters the lambs with the intent to consume an amount equal to an olive-bulk from both loaves combined outside their proper time. One can infer from this that if he had intent with regard to both of them, yes, both loaves are piggul. But if his intent was with regard to only one of them, no, the other loaf is not piggul.

מַנִּי? אִילֵּימָא רַבָּנַן – אֲפִילּוּ בְּאַחַת מֵהֶן נָמֵי! אֶלָּא פְּשִׁיטָא רַבִּי יוֹסֵי. אִי אָמְרַתְּ בִּשְׁלָמָא חַד גּוּפָא הוּא – מִשּׁוּם הָכִי מִצְטָרֵף,

Rav Naḥman continues: In accordance with whose opinion is the baraita? If we say that it is in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis of the mishna, then even if his intent was with regard to only one of them, both loaves are rendered piggul. Rather, it is obvious that the baraita is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei. Now, granted, if you say that according to Rabbi Yosei the left and right thighs of an offering are considered one body, and consequently piggul intent with regard to one thigh renders the other thigh piggul as well, then due to that reason it is understandable that if the piggul intent was for an amount equal to one total olive-bulk from both of the loaves, then the intent with regard to each loaf is combined with the other.