The Gemara brings two different braitot that each derive something different from the word ‘and his head’ that the leper is commanded to shave. One learns that the commandment of a leper to shave overrides the prohibition of shaving off one’s sidelocks. The other learns that it refers to a leper who is a nazir and even though a nazir is commanded by both a negative and positive commandment not to shave their hair, if they have leprosy, they can. The positive commandment here overrides both a negative and a positive commandment. It is suggested first that the dispute between the braitot is about whether the prohibition against cutting off sidelocks also applies in a case where one is cutting off all of his hair. Rava rejects this possibility and suggests that both agree that removing the sidelocks is only forbidden when one is not removing all the hair. But then they find it difficult to understand the first drasha and reject it and say they agree that removing all the hair is also forbidden. From here and on the basis of this understanding, the Gemara asks three questions about each braita and answers them all. Can a man shave hairs elsewhere on the body? Is there a prohibition in this based on the verse that forbids a man to wear women’s clothing? Is this a prohibition by Torah or by rabbinic law?

Nazir 58

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

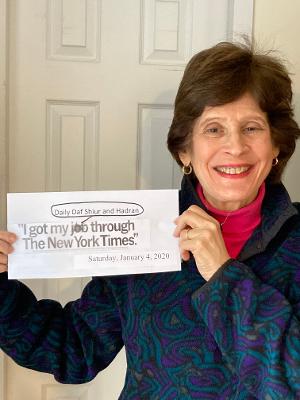

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Nazir 58

יָכוֹל אַף מְצוֹרָע כֵּן — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״רֹאשׁוֹ״. וְתַנְיָא אִידַּךְ: ״רֹאשׁוֹ״, מָה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר? לְפִי שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר גַּבֵּי נָזִיר ״תַּעַר לֹא יַעֲבֹר עַל רֹאשׁוֹ״, יָכוֹל אַף נָזִיר מְצוֹרָע כֵּן — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״רֹאשׁוֹ״.

one might have thought that even a leper should likewise be prohibited from rounding off his head. The verse therefore specifically states “his head” to teach that the mitzva for a leper to remove all the hair of his head overrides the prohibition against rounding one’s head. And it was taught in another baraita: Why must the verse state: “His head,” with regard to a leper? Since it states, with regard to a nazirite: “No razor shall come upon his head” (Numbers 6:5), one might have thought that even a nazirite leper should likewise be prohibited from shaving upon his purification. Therefore the verse states: “His head,” from which it is derived that a nazirite who contracted leprosy must shave his head like any other leper.

מַאי לָאו תַּנָּאֵי הִיא, לְמַאן דְּאָמַר מִנָּזִיר, קָסָבַר: הַקָּפַת כׇּל הָרֹאשׁ — לֹא שְׁמָהּ הַקָּפָה, וְכִי אֲתָא קְרָא — לְמִידְחֵי אֶת לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה וַעֲשֵׂה. וְאִידַּךְ סָבַר: הַקָּפַת כׇּל הָרֹאשׁ — שְׁמָהּ הַקָּפָה, וְכִי אֲתָא קְרָא — לְמִידְחֵי לָאו גְּרֵידָא?

The Gemara explains: What, is it not correct to say that this is a dispute between tanna’im? According to the one who says that the additional term “his head” is to counter a possible prohibition derived from the case of a nazirite, he holds that rounding the entire head is not called rounding, and therefore there is no need for a verse to teach that a leper can shave all the hair off his head. And when the verse “He shall shave all his hair; his head” comes, it comes to override both the prohibition: “No razor shall come upon his head,” and the positive mitzva stated with regard to a nazirite: “He shall be sacred, he shall let the locks of the hair of his head grow long” (Numbers 6:5). And the other tanna holds that rounding the entire head is called rounding, and consequently, when the verse comes, it serves to override only the prohibition against rounding one’s head.

אָמַר רָבָא: דְּכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא הַקָּפַת כׇּל הָרֹאשׁ — לֹא שְׁמָהּ הַקָּפָה. וְכִי אֲתָא קְרָא, כְּגוֹן שֶׁהִקִּיף וּלְבַסּוֹף גִּילַּח. כֵּיוָן דְּאִילּוּ גַּלְּחֵיהּ בְּחַד זִימְנָא — לָא מִיחַיַּיב, כִּי הִקִּיף וּלְבַסּוֹף גִּילַּח — נָמֵי לָא מִיחַיַּיב.

Rava said in refutation of this proof: No; it is possible that everyone agrees that rounding the entire head is not called rounding, even the tanna who maintains that the purpose of the verse is to permit a leper to round his head. And when the verse comes, it serves to address a particular case, such as one in which he rounded off only the corners of the head and ultimately shaved off the rest of his hair. Although shaving only the corners of one’s head is prohibited by the Torah, in this instance he is exempt. The reason is that since if he shaved his entire head at one time he would not be liable, then if he rounded off his head and ultimately shaved he is also not liable. Since a leper is permitted to shave all of his head, he can do so in any manner he chooses.

וּמִי כְּתַב קְרָא הָכִי? וְהָאָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ: כׇּל מָקוֹם שֶׁאַתָּה מוֹצֵא עֲשֵׂה וְלֹא תַעֲשֶׂה, אִם אַתָּה יָכוֹל לְקַיֵּים אֶת שְׁנֵיהֶם — מוּטָב, וְאִם לָאו, יָבוֹא עֲשֵׂה וְיִדְחֶה אֶת לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה.

The Gemara raises a difficulty with this explanation: And does the verse write this? Is it permitted unnecessarily to transgress a prohibition ab initio? But didn’t Reish Lakish say: Any place that you find positive mitzvot and prohibitions that clash with one another, if you can find some way to fulfill both, that is preferable; and if that is not possible, the positive mitzva will come and override the prohibition? If it is not prohibited to round the entire head, the leper can shave his hair in a permitted manner, and the Torah would not have allowed him to do so in a way that involves the violation of a prohibition.

אֶלָּא: דְּכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא הַקָּפַת כׇּל הָרֹאשׁ — שְׁמָהּ הַקָּפָה. וּמַאן דְּמוֹקֵים לִקְרָא לְמִידְחֵי לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה וַעֲשֵׂה, לָאו גְּרֵידָא מְנָלֵיהּ?

Rather, the Gemara retracts its previous explanation and states the opposite. It is that everyone agrees that rounding the entire head is called rounding. If so, the baraita that states that the verse: “He shall shave all his hair; his head” (Leviticus 14:9), comes to permit the rounding of a leper’s entire head is easily understood, as it is derived from here that a positive mitzva overrides a prohibition. But according to the one who establishes the verse “He shall shave all his hair; his head” as coming to override the prohibition and the positive mitzva of a nazirite, from where does he derive that a positive mitzva overrides only a prohibition?

יָלֵיף מִ״גְּדִילִים״. דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״לֹא תִלְבַּשׁ שַׁעַטְנֵז״, וְתַנְיָא: ״לֹא תִלְבַּשׁ שַׁעַטְנֵז״, הָא ״גְּדִילִים תַּעֲשֶׂה לָךְ״ מֵהֶם.

The Gemara answers: He derives it from the case of ritual fringes. How so? As the verse states: “You shall not wear diverse kinds, wool and linen together” (Deuteronomy 22:11), and it is taught in a baraita that although the command “You shall not wear diverse kinds” applies to most cases, the juxtaposed verse: “You shall make for you fringes” (Deuteronomy 22:12), teaches that one may prepare ritual fringes even from diverse kinds of wool and linen. This teaches that the positive mitzva of ritual fringes overrides the prohibition of diverse kinds.

וּמַאן דְּנָפְקָא לֵיהּ מֵ״רֹאשׁוֹ״, מַאי טַעְמָא לָא נָפְקָא לֵיהּ מִ״גְּדִילִים״? אָמַר לָךְ: לְכִדְרָבָא הוּא דַּאֲתָא.

The Gemara asks: And the tanna who derives the principle that a positive mitzva overrides a prohibition from “his head” stated with regard to a leper, what is the reason that he does not derive it from the verse that deals with ritual fringes? Why does he require another source? The Gemara answers: He could have said to you that the verse concerning ritual fringes does not teach that principle, as it comes for that which Rava said.

דְּרָבָא רָמֵי: כְּתִיב ״וְנָתְנוּ עַל צִיצִת הַכָּנָף״ — מִין כָּנָף, ״פְּתִיל תְּכֵלֶת״. וּכְתִיב: ״צֶמֶר וּפִשְׁתִּים יַחְדָּו״.

As Rava raises a contradiction: It is written: “And that they put on the fringe of each corner a thread of sky blue” (Numbers 15:38). The phrase “the fringe of each corner” indicates that ritual fringes must be of the same type as the corner of the robe itself, upon which they must place “a thread of sky blue.” And yet it is written: “You shall not wear diverse kinds, wool and linen together” (Deuteronomy 22:11). The juxtaposition of these two verses teaches that ritual fringes must be made from wool and linen.

הָא כֵיצַד? צֶמֶר וּפִשְׁתִּים — פּוֹטְרִים בֵּין בְּמִינָן, בֵּין שֶׁלֹּא בְּמִינָן. שְׁאָר מִינִין — בְּמִינָן פּוֹטְרִין, שֶׁלֹּא בְּמִינָן אֵין פּוֹטְרִין.

How so? How can ritual fringes be made from the same material as the garment itself and also from wool and linen? The answer is that ritual fringes of wool and linen exempt a garment and fulfill the obligation of ritual fringes whether the garment is of their own type, i.e., wool and linen, or whether it is not of their own type, i.e., all other materials. By contrast, with regard to ritual fringes of other types of materials, they exempt a garment of their own type; but they do not exempt a garment that is not of their type. According to this, the verse juxtaposing ritual fringes to diverse kinds serves to teach that ritual fringes made of wool and linen exempt any garment, not to teach that a positive mitzva overrides a prohibition.

וְהַאי תַּנָּא דְּמַפֵּיק לְ״רֹאשׁוֹ״ לְלָאו גְּרֵידָא, דְּאָתֵי עֲשֵׂה וְדָחֵי אֶת לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה וַעֲשֵׂה, מְנָלַן? נָפְקָא לֵיהּ מִ״זְּקָנוֹ״.

The Gemara continues this line of inquiry: And according to this tanna, who derives from the term “his head” that a positive mitzva overrides only a prohibition, from where do we derive the halakha that the positive mitzva of a leper’s shaving comes and overrides the prohibition and the positive mitzva of a nazirite? From where does this tanna learn that a nazirite who contracted leprosy is obligated to shave? The Gemara answers: He derives it from the verse: “He shall shave all his hair; his head and his beard” (Leviticus 14:9).

דְּתַנְיָא: ״זְקָנוֹ״, מָה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר? לְפִי שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ״וּפְאַת זְקָנָם לֹא יְגַלֵּחוּ״, יָכוֹל אַף כֹּהֵן מְצוֹרָע כֵּן — תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״זְקָנוֹ״.

As it is taught in a baraita: Why must the verse state: “His beard”? After all, a beard is already included in the phrase “all his hair.” The baraita answers: Since it is stated, with regard to priests: “Neither shall they shave off the corners of their beard” (Leviticus 21:5), one might have thought that even a priest who is a leper is included in this prohibition against shaving his beard. Therefore, the verse states: “His beard” in connection to a leper.

וּמַאן דְּמַפֵּיק לֵיהּ לְ״רֹאשׁוֹ״ לַעֲשֵׂה וְלֹא תַעֲשֶׂה, לֵילַף מִ״זְּקָנוֹ״! וְלִיטַעְמָיךְ, דְּקַיְימָא לַן בְּעָלְמָא

The Gemara asks: And the one who derives from “his head” that the mitzva of shaving overrides both the positive mitzva and prohibition of a nazirite, let him derive this principle from “his beard.” The Gemara refutes this suggestion: And according to your reasoning, that the term “his beard” teaches that a positive mitzva overrides the prohibition and positive mitzva of a nazirite, that which we maintain generally,

דְּלָא אָתֵי עֲשֵׂה וְדָחֵי אֶת לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה וַעֲשֵׂה, לֵילַף מִכֹּהֵן, דְּדָחֵי!

that a positive mitzva does not come and override a prohibition and a positive mitzva, let him derive from the fact that a leprous priest must shave that this mitzva does override a prohibition and another positive mitzva.

אֶלָּא, מִכֹּהֵן לָא יָלְפִינַן: מָה לְכֹהֵן שֶׁכֵּן לָאו שֶׁאֵינוֹ שָׁוֶה בַּכֹּל. נָזִיר מִכֹּהֵן נָמֵי לָא יָלֵיף, שֶׁכֵּן לָאו שֶׁאֵינוֹ שָׁוֶה בַּכֹּל.

Rather, he would explain that we do not derive other cases of the Torah from the halakha of a priest, for the following reason: What is different about the prohibition of a priest is that it is a prohibition that is not equally applicable to all, i.e., the prohibitions of a priest do not apply to Israelites. For the same reason, the case of a nazirite also cannot be derived from that of a priest, as the prohibition of a priest is a prohibition that is not equally applicable to all, in contrast to that of a nazirite. Consequently, the derivation from “his head” is necessary to teach that the shaving of a leper overrides the prohibition stated with regard to a nazirite.

וּמַאן דְּמוֹקֵים לְהַאי ״רֹאשׁוֹ״ בְּנָזִיר, לְמָה לִי ״זְקָנוֹ״?

The Gemara turns its attention to the other opinion: And according to the one who establishes this verse: “He shall shave all his hair; his head and his beard” (Leviticus 14:9), as referring to a nazirite, i.e., he derives from this verse the principle that in certain cases, including that of a leprous priest, a positive mitzva overrides a prohibition and a positive mitzva, why do I need the term “his beard”?

מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ, לְכִדְתַנְיָא: ״זְקָנוֹ״ מָה תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר? לְפִי שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר ״וּפְאַת זְקָנָם לֹא יְגַלֵּחוּ״, יָכוֹל אַף כֹּהֵן מְצוֹרָע כֵּן, תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״זְקָנוֹ״.

The Gemara answers: He requires it for that which is taught in a baraita with regard to the shaving of a leper, which must be performed with a razor: Why must the verse state: “His beard,” as it already stated that he shaves all his hair? Since it is stated: “Neither shall they shave off the corners of their beard” (Leviticus 21:5), one might have thought that even a priest who is a leper is included in the prohibition against shaving. The verse therefore states: “His beard,” to teach that a leprous priest must shave his beard as well.

וּמְנָלַן דִּבְתַעַר — דְּתַנְיָא: ״וּפְאַת זְקָנָם לֹא יְגַלֵּחוּ״, יָכוֹל אַף גִּילְּחוֹ בְּמִסְפָּרַיִם יְהֵא חַיָּיב, תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״וְלֹא תַשְׁחִית״. אִי לֹא תַשְׁחִית, יָכוֹל לִיקְּטָן בְּמַלְקֵט וּבְרָהִיטְנֵי חַיָּיב —

And from where do we derive that a leper must shave with a razor? As it is taught in a baraita: “Neither shall they shave off the corners of their beard” (Leviticus 21:5). One might have thought that priests should be liable even if they shaved their beards with scissors. The verse states: “And you shall not destroy the corners of your beard” (Leviticus 19:27), which teaches that the prohibition applies only to the destruction of the beard from its roots. If the sole criterion is the phrase “you shall not destroy,” one might have thought that if he extracted his hair with tweezers or removed his hair with a carpenter’s plane, he should likewise be liable due to the prohibition against destroying his hair.

תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״וּפְאַת זְקָנָם לֹא יְגַלֵּחוּ״. אֵיזוֹ גִּילּוּחַ שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ הַשְׁחָתָה — הֱוֵי אוֹמֵר: זֶה תַּעַר.

The verse therefore states: “Neither shall they shave off the corners of their beard.” Together the two verses lead to the following conclusion: Which is the type of shaving [giluaḥ] that involves destruction [hashḥata]? You must say it is a razor. The fact that it was necessary for the Torah to permit a leper to shave his beard with a razor, notwithstanding the prohibition against using this implement, proves that the positive mitzva overrides this prohibition, as derived from the term “his beard.”

וּמַאן דְּמַפֵּיק לֵיהּ לְהַאי ״רֹאשׁוֹ״ לְלָאו גְּרֵידָא, לְמָה לִי לְמִיכְתַּב ״רֹאשׁוֹ״, וּלְמָה לִי לְמִיכְתַּב ״זְקָנוֹ״?

The Gemara continues to inquire: And according to the one who derives from the term “his head” the principle that a positive mitzva overrides only a prohibition, why do I need the verse to write: “His head,” and why do I also need the same verse to write: “His beard”? Once is it derived from the phrase “his beard” that a positive mitzva overrides a positive mitzva and a prohibition, the same should certainly apply to a prohibition by itself.

מַשְׁמַע לְמִידְחֵי לָאו גְּרֵידָא, וּמַשְׁמַע לְמִידְחֵי לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה וַעֲשֵׂה. הִילְכָּךְ שָׁקוּל הוּא וְיָבוֹאוּ שְׁנֵיהֶן.

The Gemara answers: Both the term “his head” and the term “his beard” could come to teach the overriding of only a prohibition, and they also could teach the overriding of a prohibition and a positive mitzva. Since the verse is formulated in general terms, it includes a priest or a nazirite. Therefore, as it cannot be determined to which case the Torah is referring, it is even, i.e., equally balanced, and consequently let both terms come and teach this principle, one with regard to a nazirite, and the other with regard to a priest.

כֹּהֵן מִנָּזִיר לָא יָלֵיף, שֶׁכֵּן יֶשְׁנוֹ בִּשְׁאֵלָה. נָזִיר מִכֹּהֵן לָא יָלֵיף, שֶׁכֵּן לָאו שֶׁאֵינוֹ שָׁוֶה בַּכֹּל. וּבְעָלְמָא לָא יָלְפִינַן מִינַּיְיהוּ, מִשּׁוּם דְּאִיכָּא לְמִיפְרַךְ כְּדַאֲמַרַן.

The Gemara adds that both terms are necessary, as the halakha of a priest cannot be derived from that of a nazirite, as the case of a nazirite is lenient in that it is possible to dissolve naziriteship by request from a halakhic authority. Likewise, the halakha of a nazirite cannot be derived from that of a priest, as the case of a priest involves a prohibition that is not equally applicable to all. The Gemara comments: And generally, with regard to other halakhot, we cannot derive from these two cases that a positive mitzva overrides a prohibition and a positive mitzva, due to the fact that this argument can be refuted as we said here.

אָמַר רַב: מֵיקֵל אָדָם כׇּל גּוּפוֹ בְּתַעַר. מֵיתִיבִי: הַמַּעֲבִיר בֵּית הַשֶּׁחִי וּבֵית הָעֶרְוָה — הֲרֵי זֶה לוֹקֶה!

§ Rav said: A person who is not a nazirite may lighten his burden by removing all the hair of his body with a razor. One who feels he has too much hair may shave all of it off with a razor, apart from his beard and the corners of his head. The Gemara raises an objection against this from a baraita: A man who removes the hair of the armpit or the pubic hair is flogged for transgressing the prohibition: “A man shall not put on a woman’s garment” (Deuteronomy 22:5), as this behavior is the manner of women.

הָא בְּתַעַר, הָא בַּמִּסְפָּרַיִם. וְהָא רַב נָמֵי בְּתַעַר קָאָמַר! כְּעֵין תַּעַר.

The Gemara answers: In this case he is flogged because he shaved with a razor, whereas in that case Rav said it is permitted because he was referring to one who removes hair with scissors, an act that is not considered a prohibition. The Gemara raises a difficulty: But Rav said it is permitted with a razor as well. The Gemara answers: He did not mean an actual razor; rather, he said that one may use an implement that is similar to a razor, i.e., scissors that cut very close to the skin, in the manner of a razor.

אָמַר רַבִּי חִיָּיא בַּר אַבָּא אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: הַמַּעֲבִיר בֵּית הַשֶּׁחִי וּבֵית הָעֶרְוָה לוֹקֶה. מֵיתִיבִי: הַעֲבָרַת שֵׂיעָר אֵינָהּ מִדִּבְרֵי תוֹרָה, אֶלָּא מִדִּבְרֵי סוֹפְרִים. מַאי ״לוֹקֶה״ נָמֵי דְּקָאָמַר — מִדְּרַבָּנַן.

Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba said that Rabbi Yoḥanan said: A man who removes the hair of the armpit or the pubic hair is flogged. The Gemara raises an objection against this ruling: The removal of hair is not prohibited by Torah law but by rabbinic law. Why, then, is he liable to receive lashes? The Gemara explains: What does it mean that Rabbi Yoḥanan says that he is flogged? This means that he is flogged by rabbinic law, a punishment known as lashes for rebelliousness, for disobeying a rabbinic decree.