Rava and Abaye disagree regarding one who transgresses a prohibition – is one’s action effective or not? Are lqashes given only because something transpired or can one be punished merely for going against what the Torah commanded? The gemara brings tannaitic sources ranging in topic to challenge each of the opinions.

Temurah 5

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

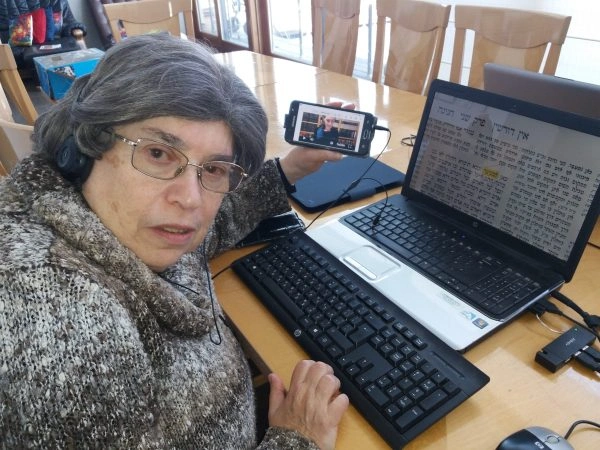

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Temurah 5

מֵיתִיבִי: אוֹנֵס שֶׁגֵּירֵשׁ, אִם יִשְׂרָאֵל הוּא — מַחְזִיר וְאֵינוֹ לוֹקֶה, וְאִי אָמְרַתְּ כֵּיוָן דַּעֲבַר אַמֵּימְרָא דְּרַחֲמָנָא לָקֵי, הָא נָמֵי לִילְקֵי! תְּיוּבְתָּא דְרָבָא.

The Gemara raises an objection from a baraita: With regard to a rapist who married and then divorced his victim, if he is an Israelite, who is permitted to marry a divorcée, he remarries her and he is not flogged. And if you say, like Rava, that since one violates the statement of the Merciful One, he is flogged, this one should be flogged as well for divorcing his victim. But according to the opinion of Abaye, it stands to reason that he should not be flogged, since his remarriage nullifies the effects of the divorce. This should be a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Rava.

אָמַר לָךְ: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא ״כׇּל יָמָיו״, כׇּל יָמָיו בַּעֲמוֹד וְהַחְזֵיר.

The Gemara answers that Rava could say to you: It is different there, as the verse states: “He may not send her away all his days” (Deuteronomy 22:29). This teaches that for all his days, he remains under the obligation to arise and remarry her. Once he remarries her, it turns out that he did not divorce her for all of his days and therefore did not violate the prohibition. This is why he is not flogged.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי, אִי לָאו דַּאֲמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״כׇּל יָמָיו״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא אִיסּוּרָא הוּא דַּעֲבַד לֵיהּ, אִי בָּעֵי לֶיהְדַּר וְאִי בָּעֵי לָא לֶיהְדַּר, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara asks: And according to the opinion of Abaye, what is derived from the phrase “all his days”? The Gemara answers: If the Merciful One did not state “all his days,” I would say that he has violated a prohibition by divorcing her, and that if he desires he may choose to remarry her, and if he so desires he may choose not to remarry her. The phrase “all his days” teaches us that he is obligated to remarry her.

לִישָּׁנָא אַחֲרִינָא. מֵיתִיבִי: אוֹנֵס שֶׁגֵּירֵשׁ — אִם יִשְׂרָאֵל הוּא מַחְזִיר וְאֵינוֹ לוֹקֶה, וְאִם כֹּהֵן הוּא לוֹקֶה וְאֵינוֹ מַחְזִיר. קָתָנֵי: ״אִם יִשְׂרָאֵל הוּא מַחְזִיר״ — תְּיוּבְתָּא דְאַבָּיֵי!

The Gemara records another version of the discussion, in which it raises an objection from the baraita: With regard to a rapist who married and then divorced his victim, if he is an Israelite, he remarries her and he is not flogged. But if he is a priest, he is flogged and he does not remarry her. The baraita teaches that if he is an Israelite he remarries her and he is not flogged, indicating that he must take her back because his divorce was not effective. This is apparently a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Abaye, who holds that transgressions are legally effective.

שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּרַחֲמָנָא אָמַר: ״כׇּל יָמָיו״, כׇּל יָמָיו בַּ״עֲמוֹד וְהַחְזֵיר״.

The Gemara answers that it is different there, as the Merciful One states: “He may not send her away all his days” (Deuteronomy 22:29), which teaches that for all his days, he remains under the obligation to arise and remarry her. Therefore, it is only in this specific case that the divorce is not effective.

וְרָבָא אָמַר לָךְ: אִי לָא כְּתַב רַחֲמָנָא ״כׇּל יָמָיו״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: לִילְקֵי וְלֶיהְדַּר, דְּהָוֵה לֵיהּ לָאו גְּרֵידָא, דִּכְתִיב: ״לֹא יוּכַל לְשַׁלְּחָהּ״. אַהָכִי כְּתַב קְרָא ״כׇּל יָמָיו״, לְשַׁוּוֹיֵיהּ לְאוֹנֵס לְלֹא תַעֲשֶׂה שֶׁנִּיתָּק לַעֲשֵׂה, דְּאֵין לוֹקִין עָלָיו.

The Gemara comments: And as for Rava, he could say to you that if the Merciful One had not stated “all his days,” I would say that the Israelite should be flogged and should still remarry her, for it is solely a prohibition that he has violated, as it is written: He may not send her away. Therefore, the verse writes “all his days,” to render the case of a rapist a prohibition whose violation can be rectified by fulfilling a positive mitzva, for which one is not flogged.

וַהֲרֵי תּוֹרֵם מִן הָרָעָה עַל הַיָּפָה, דְּרַחֲמָנָא אָמַר: ״מִכׇּל חֶלְבּוֹ״.

The Gemara objects: But there is the case of one who separates teruma from poor-quality produce for superior-quality produce, i.e., he separated teruma from the inferior produce in order to fulfill the obligation of separating teruma from other produce that is high-quality. This is prohibited, as the Merciful One states: “Out of all that is given you, you shall set apart all of that which is due to the Lord, of all the best thereof” (Numbers 18:29).

חֶלְבּוֹ — אִין, גֵּירוּעִין — לָא. וּתְנַן: אֵין תּוֹרְמִין מִן הָרָעָה עַל הַיָּפָה, וְאִם תָּרַם — תְּרוּמָתוֹ תְּרוּמָה. אַלְמָא מַהֲנֵי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְרָבָא.

And the Sages interpret this verse as follows: “Of all the best thereof,” yes, but one should not separate poor-quality produce. And yet we learned in a mishna (Terumot 2:4): One may not separate teruma from poor-quality produce for superior-quality produce, and if one did separate teruma in that manner, his teruma is valid teruma. Apparently, his action is effective, which is apparently a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Rava.

אָמַר לָךְ רָבָא: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, כְּרַבִּי אִילְעָא, דְּאָמַר רַבִּי אִילְעָא: מִנַּיִן לְתוֹרֵם מִן הָרָעָה עַל הַיָּפָה שֶׁתְּרוּמָתוֹ תְּרוּמָה? שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְלֹא תִשְׂאוּ עָלָיו חֵטְא בַּהֲרִימְכֶם אֶת חֶלְבּוֹ מִמֶּנּוּ״. אִם אֵינוֹ קָדוֹשׁ, נְשִׂיאוּת חֵטְא לָמָּה? מִיכָּן לַתּוֹרֵם מִן הָרָעָה עַל הַיָּפָה שֶׁתְּרוּמָתוֹ תְּרוּמָה.

The Gemara explains that Rava could say to you: It is different there, in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Ile’a. As Rabbi Ile’a said: From where is it derived with regard to one who separates teruma from poor-quality produce for superior-quality produce that his teruma is valid teruma? As it is stated with regard to teruma: “And you shall bear no sin by reason of it, seeing that you have set apart from it the best thereof” (Numbers 18:32). The verse defines separation from inferior produce as a transgression but teaches that it is nevertheless effective, because if it is not consecrated as teruma, why would one bear a sin for accomplishing nothing? From here it is derived with regard to one who separates teruma from poor-quality produce for superior-quality produce that his teruma is valid teruma.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי, אִי לָאו דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״וְלֹא תִשְׂאוּ עָלָיו חֵטְא״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא הָכִי אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא: עֲבֵיד מִצְוָה מִן הַמּוּבְחָר, וְאִי לָא עָבֵיד — ״חוֹטֵא״ לָא מִיקְּרֵי, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara asks: And according to the opinion of Abaye, that all transgressions are legally effective, what does the phrase “And you shall bear no sin by reason of it” teach? The Gemara answers: If the Merciful One had not stated: “And you shall bear no sin by reason of it,” I would say that this is what the Merciful One said: Perform the mitzva in the optimal manner by separating teruma from superior-quality produce, but if one did not perform the mitzva in that manner, he is not called a sinner. The verse teaches us that one who fails to perform this mitzva in the optimal manner sins.

וַהֲרֵי מִמִּין עַל שֶׁאֵינוֹ מִינוֹ, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״כׇּל חֵלֶב יִצְהָר״, לִיתֵּן חֵלֶב לָזֶה וְחֵלֶב לָזֶה, וּתְנַן: אֵין תּוֹרְמִין מִמִּין עַל שֶׁאֵינוֹ מִינוֹ, וְאִם תָּרַם — אֵין תְּרוּמָתוֹ תְּרוּמָה, אַלְמָא לָא מַהֲנֵי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְאַבָּיֵי.

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there the case of one who separates teruma from one type of produce to exempt another type of produce, as the Merciful One states: “All the best of the oil, and all the best of the wine, and of the grain, the first part of them which they give to the Lord” (Numbers 18:12)? This teaches that one is obligated to give the best of one type of produce and the best of another type of produce, each individually. And we learned in a mishna (Terumot 2:4): One may not separate teruma from one type of produce for another type, and if one did separate teruma in that manner, his teruma is not valid teruma. Apparently, the transgression is not effective. This is apparently a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Abaye.

אָמַר לָךְ אַבַּיֵּי: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא ״רֵאשִׁיתָם״ — רֵאשִׁית לָזֶה וְרֵאשִׁית לָזֶה. וְכֵן אָמַר רַבִּי אִילְעָא: ״רֵאשִׁית״.

The Gemara answers that Abaye could say to you: It is different there, as the verse repeats this prohibition and states: “The first part of them,” indicating that one must give a first part for this type of produce and a first part for that type of produce. If the verse had not taught so explicitly in this case, one would have assumed that the transgression is effective. And Rabbi Ile’a likewise says that the phrase in the verse “the first part of them” is the exception that proves the rule.

וּלְרָבָא, אִי לָאו דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״רֵאשִׁית״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא תִּירוֹשׁ וְיִצְהָר, דִּכְתִיב בְּהוּ ״חֵלֶב״ ״חֵלֶב״, דְּאֵין תּוֹרְמִין מִזֶּה עַל זֶה.

The Gemara asks: And according to the opinion of Rava, that transgressions are not effective, what does the term “the first part of them” teach? The Gemara answers: If the Merciful One had not stated: “The first part of them,” I would say that the prohibition applies only to wine and olive oil, with regard to which it is written: “Best…best,” teaching that one may not separate teruma from this type for that type.

אֲבָל תִּירוֹשׁ וְדָגָן, דָּגָן וְדָגָן, דְּחַד ״חֵלֶב״ כְּתִיב בְּהוּ, כִּי תָרֵים מֵהַאי אַהַאי — לָא לָקֵי. כְּתַב רַחֲמָנָא ״רֵאשִׁית״, לִיתֵּן חֵלֶב לָזֶה וְחֵלֶב לָזֶה.

But as for wine and grain, or one type of grain and another type of grain, with regard to which the term “best” is written only once, when one separates teruma from this grain or wine for that grain or wine, he is not held liable for transgressing Torah law, and he is not flogged. Therefore, the Merciful One writes: “The first part of them,” to teach that one must give the best of this and the best of that.

לִישָּׁנָא אַחֲרִינָא, הָא תִּירוֹשׁ וְדָגָן, דְּחַד ״חֵלֶב״ כְּתִיב בְּהוּ — תָּרֵים מֵהַאי אַהַאי. כְּתַב רַחֲמָנָא ״רֵאשִׁית״.

The Gemara records another version of the last point: But as for wine and grain, with regard to which the term “best” is written only once, one may separate teruma from this for that ab initio. Therefore, the Merciful One writes: “The first part of them,” to teach that even in the case of wine and grain, one may not separate teruma from one for the other.

וַהֲרֵי חֲרָמִים, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא: ״לֹא יִמָּכֵר וְלֹא יִגָּאֵל״, וּתְנַן: חֶרְמֵי כֹהֲנִים אֵין פּוֹדִין אוֹתָם, אֶלָּא נוֹתְנָין לַכֹּהֵן. אַלְמָא לָא מַהֲנֵי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְאַבָּיֵי.

The Gemara objects: But there is the case of dedications of property to the priests, with regard to which the Merciful One states: “No devoted item, that a man may devote unto the Lord of all that he has, whether of man or animal, or of the field of his possession, shall be sold or redeemed; every devoted item is most holy unto the Lord” (Leviticus 27:28). And we learned in a mishna (Arakhin 28b): Items dedicated to priests are not redeemed; rather, one gives them to the priest. Apparently, if one transgresses the prohibition and redeems a dedicated item, his action is not effective. This seems to be a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Abaye.

אָמַר לָךְ: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״קֹדֶשׁ קָדָשִׁים הוּא״ — בַּהֲוָויָיתוֹ יְהֵא.

The Gemara explains that Abaye could say to you: It is different there, as the Merciful One states: “Is most holy,” to teach that it shall be as it is. Once it is dedicated, its status cannot be changed by means of redemption. But in other matters the transgression is effective.

וּלְרָבָא, הַאי ״הוּא״ לְמַעוֹטֵי בְּכוֹר, דְּתַנְיָא: בִּבְכוֹר נֶאֱמַר ״לֹא תִפְדֶּה״ וְנִמְכָּר הוּא, בְּמַעֲשֵׂר נֶאֱמַר ״לֹא יִגָּאֵל״ וְאֵינוֹ נִמְכָּר, לֹא חַי וְלֹא שָׁחוּט, לא תָּם וְלֹא בַּעַל מוּם.

And according to the opinion of Rava, this term: “Is most holy,” serves to exclude the case of a firstborn offering from the prohibition of sale. As it is taught in a baraita: It is stated with regard to a firstborn offering: “But the firstling of an ox, or the firstling of a sheep, or the firstling of a goat, you shall not redeem; they are holy” (Numbers 18:17). But if it develops a blemish it may still be sold. By contrast, it is stated with regard to the animal tithe offering: “It shall not be redeemed” (Leviticus 27:33), and the animal tithe may not be sold, not when alive and not when slaughtered, not when unblemished and not when blemished.

וַהֲרֵי תְּמוּרָה, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא: ״לֹא יַחֲלִיפֶנּוּ וְלֹא יָמִיר אוֹתוֹ״, וְתָנָא: לֹא שֶׁאָדָם רַשַּׁאי לְהָמִיר, אֶלָּא שֶׁאִם הֵמִיר — מוּמָר, וְסוֹפֵג אֶת הָאַרְבָּעִים. אַלְמָא מַהֲנֵי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְרָבָא!

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there the case of substitution, with regard to which the Merciful One states: “He shall not exchange it, nor substitute it” (Leviticus 27:10), and it is taught in the mishna (2a): That is not to say that it is permitted for a person to effect substitution; rather, it means that if one substituted a non-sacred animal for a consecrated animal, the substitution takes effect, and the one who substituted the non-sacred animal incurs the forty lashes. Apparently, his action is effective, and this seems to be a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Rava.

אָמַר לָךְ: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא ״וְהָיָה הוּא וּתְמוּרָתוֹ יִהְיֶה קֹּדֶשׁ״.

The Gemara explains that Rava could say to you: It is different there, as that same verse states: “And if he shall at all substitute animal for animal, then both it and that for which it is substituted shall be holy,” which teaches that his action is effective in this context specifically.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי, אִי לָאו דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״וְהָיָה הוּא וּתְמוּרָתוֹ״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא תֵּצֵא זוֹ וְתִכָּנֵס זוֹ, קָמַשְׁמַע לַן.

And according to the opinion of Abaye, that transgressions are effective in general, that clause is still necessary, because if the Merciful One had not stated: “Both it and that for which it is substituted shall be holy,” I would say that this initially consecrated animal will leave its consecrated state, and that non-sacred animal will enter into sanctity instead. Therefore, the verse teaches us that the first animal retains its sanctity as well.

וַהֲרֵי בְּכוֹר, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״לֹא תִפְדֶּה״, וּתְנַן: יֵשׁ לָהֶן פִּדְיוֹן, וְלִתְמוּרוֹתֵיהֶן פִּדְיוֹן, חוּץ מִן הַבְּכוֹר וּמִן הַמַּעֲשֵׂר, אַלְמָא לָא מַהֲנֵי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְאַבָּיֵי.

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there the case of a firstborn offering, with regard to which the Merciful One states: “But the firstling of an ox, or the firstling of a sheep, or the firstling of a goat, you shall not redeem; they are holy” (Numbers 18:17)? And we learned in a mishna (21a): All sacrificial animals that became blemished are subject to redemption through sale, and their substitutes are also subject to redemption through sale, except for the firstborn and the animal tithe offerings. Apparently, if one attempts to redeem a firstborn offering, his action is not effective, and this seems to be a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Abaye.

אָמַר לָךְ: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא ״הֵם״, בַּהֲוָויָיתָן יְהוּ.

The Gemara explains that Abaye could say to you: It is different there, as that same verse states: “They are holy,” thereby teaching that they shall always be as they are, even if one attempts to redeem them.

וּלְרָבָא, הַאי ״הֵם״ לְמָה לֵיהּ? הֵן קְרֵיבִין, וְאֵין תְּמוּרָתָן קְרֵיבִין.

The Gemara asks: And according to Rava, who maintains that transgressions are not effective, why does he need the term “They are holy”? The Gemara answers: This term teaches that if one substituted another animal for a firstborn offering or for an animal tithe offering, they, the originally consecrated animals, are sacrificed, but their substitutes, although they have sanctity, are not sacrificed.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי — הַאי סְבָרָא מְנָא לֵיהּ? ״אִם שׁוֹר אִם שֶׂה לַה׳ הוּא״ — לַה׳ קָרֵיב, וְאֵין תְּמוּרָתוֹ קְרֵיבָה.

The Gemara asks: And according to Abaye, from where does he derive this conclusion that the substitutes are not sacrificed? The Gemara answers: The verse states concerning firstborn offerings: “Whether it be ox or sheep, it is the Lord’s” (Leviticus 27:26). One can infer from this wording that it is sacrificed to the Lord but its substitute is not sacrificed.

וְרָבָא, אִין הָכִי נָמֵי דְּמֵהָהוּא קְרָא, אֶלָּא ״הֵם״ לְמָה לִי? לִימֵּד עַל בְּכוֹר וּמַעֲשֵׂר שֶׁנִּתְעָרֵב דָּמָן בְּכׇל הָעוֹלִין שֶׁקְּרֵיבִין לְגַבֵּי מִזְבֵּחַ.

The Gemara asks: And what does Rava derive from that verse? The Gemara responds: Yes, it is indeed so that he, like Abaye, derives from that verse, not from Numbers 18:17 as originally suggested, the halakha that the substitute of a firstborn is not sacrificed. Rather, why do I need the term “They are holy” which appears in that verse? It teaches with regard to a firstborn offering or an animal tithe offering whose blood was mixed with the blood of any other offering brought upon the altar that the blood is nevertheless sacrificed on the altar as it would have been individually.

וְאַבָּיֵי, הַאי סְבָרָא מְנָא לֵיהּ? מִ״וְּלָקַח מִדַּם הַפָּר וּמִדַּם הַשָּׂעִיר״, וַהֲלֹא דַּם הַפָּר מְרוּבֶּה מִשֶּׁל שָׂעִיר! מִיכָּן לָעוֹלִין שֶׁאֵין מְבַטְּלִין זֶה אֶת זֶה, דְּתַנְיָא: ״וְלָקַח מִדַּם הַפָּר וּמִדַּם הַשָּׂעִיר״ — שֶׁיְּהוּ מְעוֹרָבִין, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה.

The Gemara asks: And Abaye, from where does he derive this conclusion, that such blood is sacrificed? The Gemara answers: He derives it from the verse concerning the High Priest’s service on Yom Kippur: “And he shall take of the blood of the bull, and of the blood of the goat, and put it upon the corners of the altar” (Leviticus 16:18). One might ask: But isn’t there more blood of the bull than of the goat? Why is the blood of the goat not nullified? From here it is derived that offerings brought upon the altar do not nullify one another, as it is taught in a baraita that the phrase in the verse “And he shall take of the blood of the bull, and of the blood of the goat” serves to teach that they must be mixed. This is the statement of Rabbi Yoshiya. Accordingly, Abaye derives that mixtures of blood may be sacrificed.

וְרָבָא, הָתָם — מִזֶּה בִּפְנֵי עַצְמוֹ וּמִזֶּה בִּפְנֵי עַצְמוֹ, וְסָבַר לַהּ כְּרַבִּי יוֹנָתָן.

And as for Rava, he holds that there, the High Priest would take from this blood of the bull by itself and from that blood of the goat by itself, rather than mixing them together. And in this matter, he holds in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yonatan, who disagrees with Rabbi Yoshiya.

וַהֲרֵי מַעֲשֵׂר, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״לֹא יִגָּאֵל״, וּתְנַן: יֵשׁ לָהֶן פִּדְיוֹן וְלִתְמוּרוֹתֵיהֶן, חוּץ מִן הַבְּכוֹר וּמִן הַמַּעֲשֵׂר, אַלְמָא לָא מַהֲנֵי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְאַבָּיֵי.

The Gemara continues its analysis of the dispute between Abaye and Rava. But isn’t there the case of an animal tithe offering, with regard to which the Merciful One states: “It shall not be redeemed” (Leviticus 27:33)? And we learned in a mishna (21a): All sacrificial animals that became blemished are subject to redemption through sale, and their substitutes are also subject to redemption through sale, except for the firstborn and the animal tithe offering. Apparently, if one attempts to redeem an animal tithe offering, his act is not effective, and this seems to be a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Abaye.

אָמַר לָךְ: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּיָלֵיף ״עֲבָרָה״ ״עֲבָרָה״ מִבְּכוֹר.

The Gemara explains that Abaye could say to you: It is different there, as one derives that halakha from the halakha of a firstborn offering, by verbal analogy between the term “avara” that is stated with regard to an animal tithe offering: “Whatsoever passes [ya’avor] under the rod” (Leviticus 27:32), and the term “avara” that is stated with regard to a firstborn offering: “You shall set apart [veha’avarta] to the Lord all that opens the womb” (Exodus 13:12). It was already derived above that a firstborn offering cannot be redeemed. But in general, transgressions are effective.

הֲרֵי הִקְדִּימָהּ תְּרוּמָה לַבִּיכּוּרִים, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״מְלֵאָתְךָ וְדִמְעֲךָ לֹא תְאַחֵר״, וּתְנַן: הַמַּקְדִּים, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהוּא בְּלֹא תַעֲשֶׂה — מַה שֶּׁעָשָׂה עָשׂוּי!

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there the case of one who separated teruma prior to the separation of the first fruits, with regard to which the Merciful One states: “You shall not delay to offer of the fullness of your harvest and the outflow of your presses” (Exodus 22:28)? The verse was expounded earlier (4b) as teaching that one must separate first fruits before separating teruma. And we learned in a mishna (Terumot 3:6): If one separates teruma prior to the separation of the first fruits, although he has transgressed a prohibition, what he did is done, and produce has the status of teruma. This appears to refute the opinion of Rava.

אָמַר לָךְ רָבָא: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא ״מִכֹּל מַעְשְׂרוֹתֵיכֶם תָּרִימוּ תְּרוּמָה״.

The Gemara explains that Rava could say to you: It is different there, as the verse states: “From all that is given you, you shall set apart that which is the Lord’s teruma” (Numbers 18:29), thereby teaching that the separation of teruma is effective in any case. But in general, transgressions are not effective.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי מִיבַּעְיָא לֵיהּ, כִּדְאָמַר רַב פָּפָּא לְאַבָּיֵי: אֶלָּא מֵעַתָּה, אֲפִילּוּ הִקְדִּימוֹ בִּכְרִי נָמֵי נִיפְּטַר!

And according to the opinion of Abaye that transgressions are generally effective, that verse is required to teach another halakha, as Rav Pappa said to Abaye (Beitza 13b): Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish stated that if the first tithe was separated while the grain was still on the stalks, that amount is exempt from teruma, even though the amount of teruma the priest receives is thereby reduced. If that is so, then even if the Levite preceded the priest by taking the first tithe after the grain had been threshed and arranged in a pile, we should exempt that grain from the obligation of teruma as well.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ: עָלֶיךָ אָמַר קְרָא ״מִכֹּל מַעְשְׂרוֹתֵיכֶם תָּרִימוּ״.

Abaye said to Rav Pappa: With regard to your claim, the verse states: “From all that is given you, you shall set apart.” This verse teaches that the Levites must designate a portion of all the gifts they receive and give it to the priests, even if they received them before teruma had been separated.

מָה רָאִיתָ לְרַבּוֹת אֶת הַכְּרִי וּלְהוֹצִיא אֶת הַשִּׁיבֳּלִין? מְרַבֶּה אֲנִי אֶת הַכְּרִי, שֶׁיֶּשְׁנוֹ בִּכְלַל דִּיגּוּן, וּמוֹצִיא אֲנִי אֶת הַשִּׁיבֳּלִין, שֶׁאֵינָן בִּכְלַל דִּיגּוּן.

Rav Pappa asked: What did you see that leads you to include the first tithe taken from the pile in the category: “All that is given,” and to exclude that which is taken from the stalks? Abaye answered: I include a tithe taken from the pile, as it has been processed to the point where it is included in the category of grain, since it is written: “The first fruits of your grain…you shall give him” (Deuteronomy 18:4); and I exclude a tithe taken from the stalks, as it is not included in the category of grain and is not yet obligated in teruma.

וַהֲרֵי אַלְמָנָה לְכֹהֵן גָּדוֹל, דְּרַחֲמָנָא אָמַר ״אַלְמָנָה וּגְרוּשָׁה… לֹא יִקָּח״, וּתְנַן: כׇּל מָקוֹם שֶׁיֵּשׁ קִדּוּשִׁין וְיֵשׁ עֲבֵירָה — הַוָּלָד הוֹלֵךְ אַחַר הַפָּגוּם.

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there the case of a widow betrothed to a High Priest, with regard to which the Merciful One stated: “A widow, or one divorced, or a profaned woman, or a harlot, these shall he not take; but a virgin of his own people shall he take to wife. And he shall not profane his seed among his people” (Leviticus 21:14–15)? And we learned in a mishna (Kiddushin 66b): Any case where there is a valid betrothal and yet there is a transgression, the offspring follows the flawed lineage. For example, if a widow, who may not marry a High Priest, nevertheless did so, the offspring may not marry a priest. Still, the marriage is in force, contrary to the opinion of Rava.

שָׁאנֵי הָכָא, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״לֹא יְחַלֵּל זַרְעוֹ״.

The Gemara explains that Rava could say: It is different there, as the verse states: “And he shall not profane [lo yeḥallel] his seed.” The verse states only that the offspring is profaned, not that he has the status of a mamzer, which would hold for one born of a union between two people with regard to whom marriage cannot take effect. Rava infers from the verse that the betrothal of a High Priest and a widow specifically does take effect. But in general, transgressions are not effective.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי, נֵימָא קְרָא ״לֹא יַחֵל״, מַאי ״לֹא יְחַלֵּל״? אֶחָד לוֹ, וְאֶחָד לָהּ.

And according to the opinion of Abaye, that transgressions are generally effective, what is derived from that phrase? Abaye can say: If it merely means to teach that the betrothal takes effect, let the verse state simply: Lo yaḥel, which would have the same meaning. What is indicated by the use of the longer form: Lo yeḥallel? This teaches that there are two profanations: One for him, i.e., that the offspring is profaned, and one for her, i.e., that the mother is disqualified from marrying even a common priest.

וַהֲרֵי הִקְדִּישׁ בַּעֲלֵי מוּמִין לַמִּזְבֵּחַ, דְּרַחֲמָנָא אָמַר: ״כֹּל אֲשֶׁר בּוֹ מוּם לֹא תַקְרִיבוּ״, וּתְנַן: הַמַּקְדִּישׁ בַּעֲלֵי מוּמִין לְגַבֵּי מִזְבֵּחַ, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁהוּא בְּלֹא תַעֲשֶׂה — מַה שֶּׁעָשָׂה עָשׂוּי, תְּיוּבְתָּא דְרָבָא!

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there the case of one who consecrated blemished animals for sacrifice on the altar, with regard to which the Merciful One states: “But whatsoever has a blemish, that you shall not bring; for it shall not be acceptable for you” (Leviticus 22:20)? And we learned in a baraita: If one consecrates blemished animals for sacrifice on the altar, even though he has transgressed a prohibition, what he did is done, and the consecration takes effect. This is apparently a conclusive refutation of the opinion of Rava.

אָמַר לָךְ רָבָא: שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא ״וּלְנֶדֶר לֹא יֵרָצֶה״ — רִצּוּי הוּא דְּלָא מְרַצֵּה, הָא מִיקְדָּשׁ קָדְשִׁי.

The Gemara explains that Rava could say to you: It is different there, as the verse states with regard to blemished animals: “But for a vow it shall not be accepted” (Leviticus 22:23). Since the verse specifies only that it is its sacrifice which does not effect acceptance, one may consequently infer that if one consecrates them, they are still consecrated. But in general, transgressions are not effective.

וּלְאַבָּיֵי, אִי דְּלָא אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא ״וּלְנֶדֶר לֹא יֵרָצֶה״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא: כְּעוֹבֵר מִצְוָה וְכָשֵׁר, קָמַשְׁמַע לַן.

And according to the opinion of Abaye, that transgressions are generally effective, what does this phrase teach? Abaye can say that if the Merciful One had not stated: “But for a vow it shall not be accepted,” I would say that one who consecrated it is considered like one who transgressed a mitzva but the offering is still fit to be sacrificed. The verse therefore teaches us that it may not be sacrificed as an offering.

וַהֲרֵי מַקְדִּישׁ תְּמִימִין לְבֶדֶק הַבַּיִת, דְּאָמַר רַחֲמָנָא:

The Gemara objects: But there is the case of one who consecrates unblemished animals for Temple maintenance, with regard to which the Merciful One states: