Rav Nachman and Rav Sheshet disagree regarding whether impurity is pushed aside or entirely permitted in cases involving the public. The gemara brings three tannaitic sources (including Tosefta Menachot Chapter 3) to raise difficulties against Rav Nachman, but answers them. From the answers, it becomes clear that Rav Nachman held that there were a few exceptions to the rule and there are cases where the impurity is not entirely permitted. Then they bring one source against Rav Sheshet and answer it by saying that it’s a tannaitic debate whether or not impurity is pushed aside or entirely permitted. The tannaitic debate relates to the tzitz of the Kohen Gadol and whether it worked while it was on his forehead only or even if it were hanging on a peg. Some of the other sources brought also mentioned the tzitz and discussed when it was needed.

Yoma 7

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

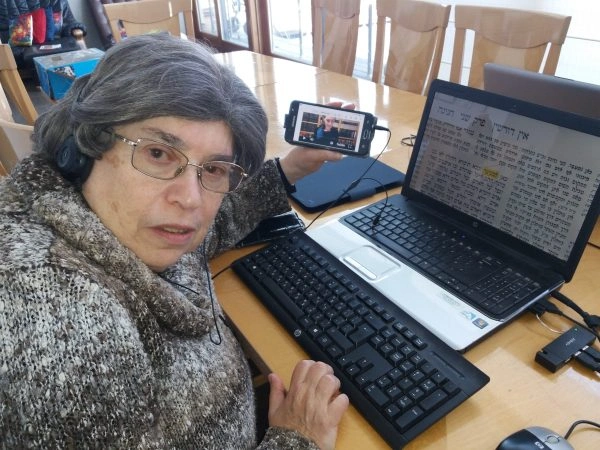

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Yoma 7

דְּכֹל טוּמְאַת מֵת בְּצִיבּוּר רַחֲמָנָא שַׁרְיַיהּ.

as in all situations of impurity imparted by corpses in cases involving the public, the Merciful One permits those who are impure to perform the Temple service.

אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: מְנָא אָמֵינָא לַהּ, דְּתַנְיָא: הָיָה עוֹמֵד וּמַקְרִיב מִנְחַת הָעוֹמֶר וְנִטְמֵאת בְּיָדוֹ, אוֹמֵר וּמְבִיאִין אַחֶרֶת תַּחְתֶּיהָ. וְאִם אֵין שָׁם אֶלָּא הִיא, אוֹמְרִין לוֹ: הֱוֵי פִּקֵּחַ וּשְׁתוֹק.

The Gemara analyzes the rationale behind the two opinions. Rav Sheshet said: From where do I derive to say that impurity is overridden in cases involving the public? It is as it was taught in a baraita: If a priest was standing and sacrificing the omer meal-offering and it became impure in his hand, the priest, who was aware of what transpired, says that it is impure and the priests bring another meal-offering in its stead. And if the meal-offering in his hand is the only meal-offering available there, the other priests say to him: Be shrewd and keep silent; do not tell anyone that it is impure.

קָתָנֵי מִיהַת אוֹמֵר וּמְבִיאִין אַחֶרֶת תַּחְתֶּיהָ! אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן: מוֹדֵינָא הֵיכָא דְּאִיכָּא שִׁירַיִים לַאֲכִילָה.

In any case, it is teaching that he says that it is impure and the priests bring another meal-offering in its place. Apparently, when it is possible to perform the service in a state of purity, even in cases involving the public, it is preferable to do so, and the prohibition of ritual impurity is not permitted. Rav Naḥman rejected the proof and said: I concede that in a case where there are remnants of the offering designated for eating it must be performed in purity wherever possible. Although it is permitted to sacrifice an offering when impure, the mitzva to eat portions of the offering must be performed in a state of purity. Therefore, in cases where portions of the offering are eaten, the preference is to sacrifice the offering in a state of purity.

מֵיתִיבִי: הָיָה מַקְרִיב מִנְחַת פָּרִים וְאֵילִים וּכְבָשִׂים, וְנִטְמֵאת בְּיָדוֹ, אוֹמֵר וּמְבִיאִין אַחֶרֶת תַּחְתֶּיהָ. וְאִם אֵין שָׁם אֶלָּא הִיא, אוֹמְרִין לוֹ: הֱוֵי פִּקֵּחַ וּשְׁתוֹק.

The Gemara raises an objection to the opinion of Rav Naḥman from the Tosefta: If a priest was sacrificing the meal-offering accompanying the sacrifice of bulls, rams, or sheep, and the meal-offering became impure in his hand, the priest says that it is impure and the priests bring another meal–offering in its stead. And if the meal-offering in his hand is the only meal-offering available there, the other priests say to him: Be shrewd and keep silent; do not tell anyone that it is impure.

מַאי לָאו, פָּרִים אֵילִים וּכְבָשִׂים דְּחַג!

What, is it not referring to the bulls, rams, and sheep of the festival of Sukkot, which are communal offerings that are not eaten? Apparently, even in cases of communal offerings, the priests seek to perform the service in a state of purity and the prohibition of impurity is not permitted but merely overridden.

אָמַר לְךָ רַב נַחְמָן: לָא: פָּרִים — פַּר עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה, אַף עַל גַּב דְּצִיבּוּר הוּא, כֵּיוָן דְּלָא קְבִיעַ לֵיהּ זְמַן — מַהְדְּרִינַן. אֵילִים — בְּאֵילוֹ שֶׁל אַהֲרֹן, דְּאַף עַל גַּב דִּקְבִיעַ לֵיהּ זְמַן, כֵּיוָן דְּיָחִיד הוּא — מְהַדְּרִינַן. כְּבָשִׂים — בְּכֶבֶשׂ הַבָּא עִם הָעוֹמֶר, דְּאִיכָּא שִׁירַיִים לַאֲכִילָה.

Rav Naḥman could have said to you: No, the bulls mentioned in the Tosefta are not standard communal offerings. Rather, the reference is to the bull sacrificed when the entire community engages in idolatry unwittingly. Although this offering is a communal offering, since it has no specific time fixed for its sacrifice, we seek out a pure meal-offering in its stead.

Similarly, the rams mentioned in the Tosefta are not additional offerings of the Festival. Rather, the reference is to the ram of Aaron sacrificed on Yom Kippur. Although it has a specific time fixed for its sacrifice, since it is an offering brought by an individual, the High Priest, we seek out a pure meal-offering in its stead, as service in a state of impurity is permitted only for communal offerings.

The sheep mentioned are not those for the daily offerings or the additional offerings of the Festival. Rather, the reference is to the sheep that accompanies the omer meal-offering, as in that case, there are remnants designated for eating. Therefore, the meal-offering must be offered in purity.

מֵיתִיבִי: דָּם שֶׁנִּטְמָא וּזְרָקוֹ, בְּשׁוֹגֵג — הוּרְצָה, בְּמֵזִיד — לֹא הוּרְצָה. כִּי תַּנְיָא הָהִיא דְּיָחִיד.

The Gemara raises an additional objection to the opinion of Rav Naḥman: With regard to blood that became impure and a priest sprinkled it on the altar, if he did so unwittingly, the offering is accepted. If he sprinkled the blood intentionally, the offering is not accepted. Apparently, even in cases involving the public, performing service in the Temple in a state of impurity is not permitted. This objection is rejected: When that baraita was taught, it was with regard to the offering of an individual, where the prohibition of impurity is certainly in effect.

תָּא שְׁמַע: עַל מָה הַצִּיץ מְרַצֶּה, עַל הַדָּם וְעַל הַבָּשָׂר וְעַל הַחֵלֶב שֶׁנִּטְמָא, בֵּין בְּשׁוֹגֵג בֵּין בְּמֵזִיד, בֵּין בְּאוֹנֶס בֵּין בְּרָצוֹן, בֵּין בְּיָחִיד בֵּין בְּצִיבּוּר. וְאִי סָלְקָא דַּעְתָּךְ טוּמְאָה הֶיתֵּר הִיא בְּצִיבּוּר — לְמָה לִי לְרַצּוֹיֵי?

The Gemara continues: Come and hear a different argument based on that which was taught in a baraita. For what does the frontplate worn by the High Priest effect acceptance? It effects acceptance for the blood, for the flesh, and for the fat of an offering that became impure in the Temple, whether it became impure unwittingly or whether it became impure intentionally, whether it was due to circumstances beyond his control or whether it was done willfully, whether it was in the framework of an individual offering or whether it was in the framework of a communal offering. And if it enters your mind that impurity is permitted in cases involving the public, why do I need the frontplate to effect acceptance? If the prohibition of impurity is permitted, no pardon is necessary.

אָמַר לְךָ רַב נַחְמָן: כִּי קָתָנֵי ״הַצִּיץ מְרַצֶּה״ אַדְּיָחִיד. וְאִיבָּעֵית אֵימָא: אֲפִילּוּ תֵּימָא בְּצִיבּוּר, בְּהָנָךְ דְּלָא קְבִיעַ לָהּ זְמַן.

The Gemara responds that Rav Naḥman could have said to you: When the baraita teaches that the frontplate effects acceptance it is not referring to the entire list of items cited in the baraita; it is referring to an individual offering brought in impurity, not to a communal offering. The communal offering is mentioned only in the sense that in that case too, impurity is permitted, albeit for a different reason. Or if you wish, say instead: Even if you say that the frontplate effects acceptance for a communal offering, it is only for those offerings that lack a fixed time. Rav Naḥman concedes that with regard to those communal offerings that have no specific time fixed for their sacrifice, the prohibition of performing the service in impurity remains in effect and requires the acceptance effected by the frontplate.

מֵיתִיבִי: ״וְנָשָׂא אַהֲרֹן אֶת עֲוֹן הַקֳּדָשִׁים״, וְכִי אֵיזֶה עָוֹן הוּא נוֹשֵׂא? אִם עֲוֹן פִּיגּוּל — הֲרֵי כְּבָר נֶאֱמַר: ״לֹא יֵרָצֶה״, וְאִם עֲוֹן נוֹתָר — הֲרֵי כְּבָר נֶאֱמַר: ״לֹא יֵחָשֵׁב״,

The Gemara raises an objection. It is stated: “And Aaron will gain forgiveness for the sin committed in the sacred things that the children of Israel shall hallow in all their sacred gifts, and it shall be always upon his forehead that they may be accepted favorably before the Lord” (Exodus 28:38). And for which sin does the frontplate gain forgiveness? If it is for the sin of piggul, an offering disqualified by the intention to sacrifice or eat it after the permitted time, it has already been stated: “And if it is eaten at all on the third day, it is piggul; it shall not be accepted” (Leviticus 19:7). There is no acceptance of an offering that became piggul. And if it is for the sin of notar, meat of an offering left after the permitted time for eating it passed, it has already been stated: “And if any of the flesh of the sacrifice of his peace-offerings is eaten on the third day, it shall not be accepted, neither shall it be credited to he who offered it” (Leviticus 7:18).

הָא אֵינוֹ נוֹשֵׂא אֶלָּא עֲוֹן טוּמְאָה שֶׁהוּתְּרָה מִכְּלָלָהּ בְּצִיבּוּר. וְקַשְׁיָא לְרַב שֵׁשֶׁת! תַּנָּאֵי הִיא. דְּתַנְיָא: צִיץ, בֵּין שֶׁיֶּשְׁנוֹ עַל מִצְחוֹ בֵּין שֶׁאֵינוֹ עַל מִצְחוֹ — מְרַצֶּה, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן.

Apparently, the frontplate gains forgiveness only for the sin of impurity, which was exempted from its general prohibition in cases involving the public. This poses a difficulty to the opinion of Rav Sheshet, who said that the prohibition of impurity is overridden in cases involving the public, as the baraita clearly states that impurity is permitted. The Gemara responds: According to Rav Sheshet, the question of whether the prohibition of impurity is permitted or overridden in cases involving the public is the subject of a dispute between tanna’im, as it was taught in a baraita: The frontplate effects acceptance whether it is on the High Priest’s forehead or whether it is not on the High Priest’s forehead when the offering becomes impure. This is the statement of Rabbi Shimon.

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: עוֹדֵהוּ עַל מִצְחוֹ — מְרַצֶּה. אֵין עוֹדֵהוּ עַל מִצְחוֹ — אֵינוֹ מְרַצֶּה. אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן: כֹּהֵן גָּדוֹל בְּיוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים יוֹכִיחַ, שֶׁאֵין עוֹדֵהוּ עַל מִצְחוֹ, וּמְרַצֶּה!

Rabbi Yehuda says: As long as it is on his forehead it effects acceptance; if it is no longer on his forehead it does not effect acceptance. Rabbi Shimon said to Rabbi Yehuda: The case of the High Priest on Yom Kippur can prove that your statement is incorrect, as on Yom Kippur when the High priest wears only four linen garments the frontplate is no longer on his forehead, and it still effects acceptance.

אָמַר לוֹ רַבִּי יְהוּדָה: הַנַּח לְכֹהֵן גָּדוֹל בְּיוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים, שֶׁטּוּמְאָה הוּתְּרָה לוֹ בְּצִיבּוּר. מִכְּלָל דְּרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן סָבַר טוּמְאָה דְּחוּיָה הִיא בְּצִיבּוּר.

Rabbi Yehuda said to him: Leave the case of the High Priest on Yom Kippur, as the atonement of the frontplate is unnecessary because the prohibition of performing the Temple service in impurity is permitted in cases involving the public. Learn by inference that Rabbi Shimon holds that impurity is overridden in cases involving the public, and that is why the atonement of the frontplate is necessary. The dispute between Rav Sheshet and Rav Naḥman is based on a tannaitic dispute, and the baraita cited above is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: בְּנִשְׁבַּר הַצִּיץ דְּכוּלֵּי עָלְמָא לָא פְּלִיגִי דְּלָא מְרַצֶּה. כִּי פְּלִיגִי דִּתְלֵי בְּסִיכְּתָא, רַבִּי יְהוּדָה סָבַר: ״עַל מֵצַח … וְנָשָׂא״,

The Gemara proceeds to analyze the tannaitic dispute between Rabbi Shimon and Rabbi Yehuda. Abaye said: In a case where the frontplate broke, everyone, including Rabbi Shimon, agrees that the frontplate no longer effects acceptance. When they disagree is in a case where the frontplate is not on his forehead but is hanging on a peg. Rabbi Yehuda holds that the verse: “And it shall be on the forehead of Aaron and Aaron shall gain forgiveness for the sin committed in the sacred things” (Exodus 28:38) means that the frontplate atones for sin as long as it is on his forehead.

וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן סָבַר ״תָּמִיד לְרָצוֹן לִפְנֵי ה׳״. מַאי ״תָּמִיד״? אִילֵּימָא: תָּמִיד עַל מִצְחוֹ, מִי מַשְׁכַּחַתְּ לַהּ?! מִי לָא בָּעֵי מֵיעַל לְבֵית הַכִּסֵּא, וּמִי לָא בָּעֵי מֵינַם?! אֶלָּא: תָּמִיד מְרַצֶּה הוּא.

And Rabbi Shimon holds that emphasis should be placed on the end of that verse: “It shall be always upon his forehead that they may be accepted before the Lord.” From this, Rabbi Shimon derived that the frontplate always effects acceptance, even when it is not upon the High Priest’s forehead, as what is the meaning of the word always in the verse? If we say that it means that the frontplate must always be on the High Priest’s forehead, do you find that situation in reality? Doesn’t he need to enter the bathroom, when he must remove the frontplate bearing the name of God? Similarly, doesn’t he need to sleep, at which time he removes the priestly vestments? Rather, it means that the frontplate always effects acceptance, whether or not it is on his forehead.

וּלְרַבִּי יְהוּדָה נָמֵי, הָא כְּתִיב ״תָּמִיד״! הָהוּא תָּמִיד שֶׁלֹּא יַסִּיחַ דַּעְתּוֹ מִמֶּנּוּ, כִּדְרַבָּה בַּר רַב הוּנָא. דְּאָמַר רַבָּה בַּר רַב הוּנָא: חַיָּיב אָדָם לְמַשְׁמֵשׁ בִּתְפִילָּיו בְּכׇל שָׁעָה וְשָׁעָה, קַל וָחוֹמֶר מִצִּיץ:

The Gemara asks: And according to Rabbi Yehuda as well, isn’t it written: “Always”? Clearly it does not mean that the frontplate must always be on his forehead. The Gemara answers: That term: “Always,” teaches that the High Priest must always be aware that the frontplate is on his head, and that he should not be distracted from it. This is in accordance with the statement of Rabba bar Rav Huna, as Rabba bar Rav Huna said: A person must touch the phylacteries on his head and on his arm each and every hour, to maintain awareness of their presence. This is derived by means of an a fortiori inference from the frontplate: