אם מישהו מוצא שטר חוב ברחוב ולא ברור אם נפרע או לא, האם ניתן להחזירו לנושה? לדעת רבי מאיר, זה תלוי אם צוין בשטר שעבוד קרקעות – אם כן, לא מחזירים את השטר שמא יגבו קרקע שלא כדין. חכמים חולקים על רבי מאיר וקובעים שבכל מקרה לא מחזירים את השטר. ישנן שתי הצעות להסביר את מקרה המשנה – האם מדובר במקרה בו הלווה מסכים שההלוואה טרם נפרעה או שמא הלווה טוען שנפרעה? ראשית, הגמרא מציעה את ההסבר הראשון (הלווה מודה) ומסבירה את עמדתו של רבי מאיר שיש לחשוש לבעיה בתאריך הכתוב בשטר ועל פי זה יגבו נכסים מלקוחות שלא כדין מתאריך שהוקדם להלוואה. אולם, מביאים סתירה ממשנה בבבא בתרא שאין חשש כזה. רב אסי ואביי פותרים את הסתירה בדרכים שונות. מעלים קושיות מול שניהם ופותרים אותם. בפתרון לקושי על אביי, הם מניחים כי אביי סבור כי רבי מאיר חושש שאם יש שעבוד נכסים, הנושה והלווה עלולים לקשר יחד לשקר על מנת להחזיר ולחלוק קרקע שמכר הלווה (חוששים לפרעון ולקנוניא). מכיוון ששמואל אינו חושש לקנוניא, עליו להסביר כרב אסי או מציעים שאולי הוא הבין את המקרה במשנתינו בצורה אחרת – שהלווה טוען שהוא פרע את החוב. אם כן, הבסיס להבחנה של רבי מאיר הוא שהוא סובר שאם מסמך אינו כולל שעבוד נכסים, לא ניתן לגבות אותו כלל. לכן, אם אין שעבוד נכסים, ניתן להחזירו לנושה ללא חשש לגבייתו. ובכל זאת, הוא מוחזר כדי שהנושה יוכל להשתמש בנייר לשימושים אחרים, כגון לכיסוי כד. אם יש לה שעבוד נכסים, אנו סומכים על הלווה שהוא פרע את החוב ולא מחזירים את השטר למלווה (כי אם יגבה, יגבה שלא כדין). יש מחלוקת בין רבי יוחנן ורבי אלעזר ביאזה מקרה חולקים רבי מאיר וחכמים כשהלווה מודה שעדיין קיימת הלוואה או כשטוען שפרוע. כל אחד מהם מסביר לפי עמדתו את בסיס למחלוקת בין רבי מאיר לחכמים. הגמרא מציגה ברייתא ומסבירה שהיא תומכת בעמדת רבי יוחנן ומעלה קושי אחד נגד עמדתו של רבי אלעזר ושניים נגד שמואל. אולם מתעורר קושי כי הברייתא חולקת בשני עניינים על רבי אלעזר!

רוצה להקדיש לימוד?

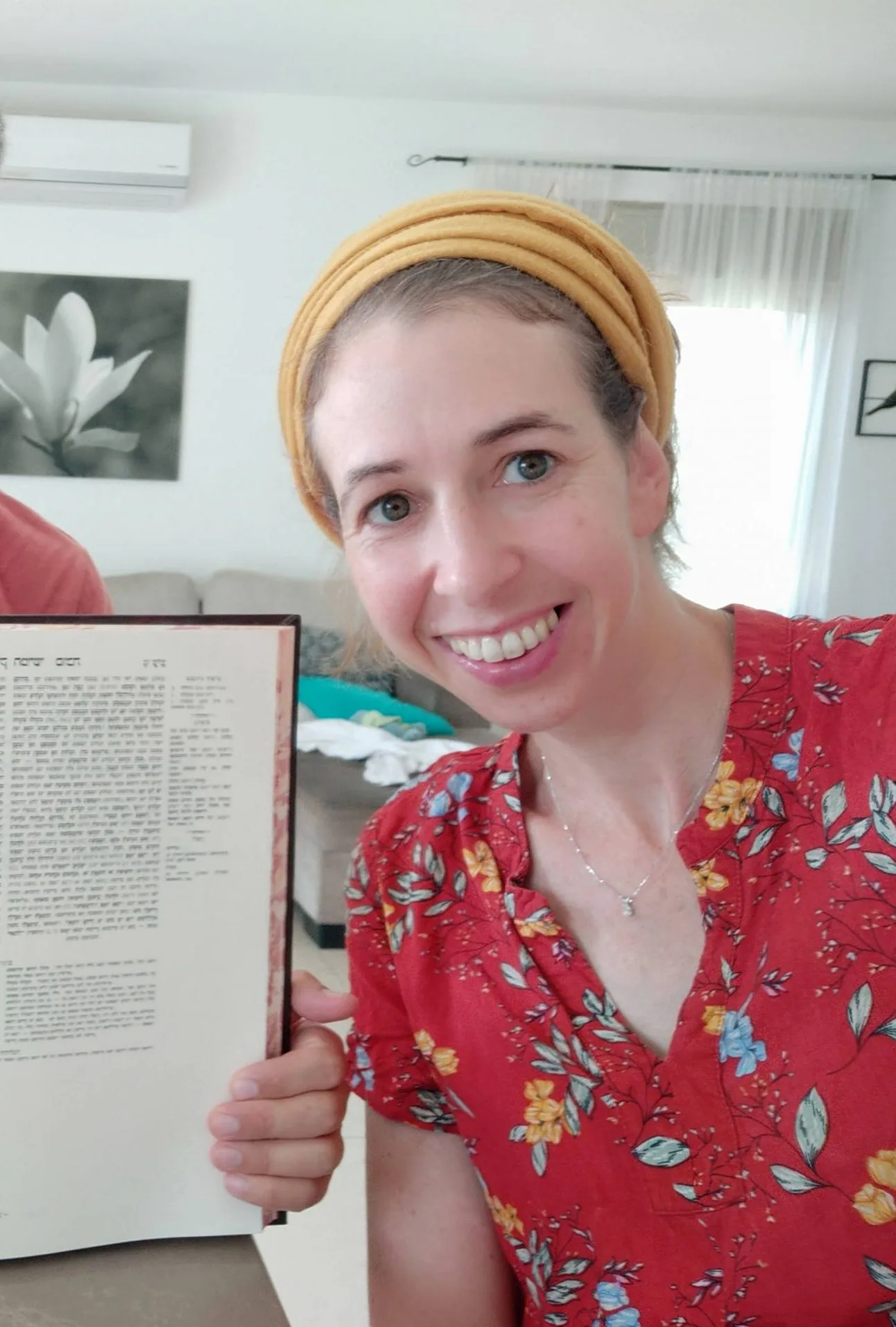

חדשה בלימוד הגמרא?

זה הדף הראשון שלך? איזו התרגשות עצומה! יש לנו בדיוק את התכנים והכלים שיעזרו לך לעשות את הצעדים הראשונים ללמידה בקצב וברמה שלך, כך תוכלי להרגיש בנוח גם בתוך הסוגיות המורכבות ומאתגרות.

פסיפס הלומדות שלנו

גלי את קהילת הלומדות שלנו, מגוון נשים, רקעים וסיפורים. כולן חלק מתנועה ומסע מרגש ועוצמתי.

בבא מציעא יג

בִּשְׁטָרֵי הַקְנָאָה, דְּהָא שַׁעְבֵּיד נַפְשֵׁיהּ.

This mishna is referring not to one who finds an ordinary promissory note but to one who finds deeds of transfer. This refers to a promissory note that establishes a lien on the debtor’s property from the date the note is written, regardless of when he borrows the money. Because the debtor obligated himself from that date, the creditor has the legal right to repossess his land from any subsequent purchasers.

אִי הָכִי, מַתְנִיתִין דְּקָתָנֵי: ״אִם יֵשׁ בָּהֶן אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים לֹא יַחֲזִיר״, וְאוֹקֵימְנָא כְּשֶׁחַיָּיב מוֹדֶה, וּמִשּׁוּם שֶׁמָּא כָּתַב לִלְוֹת בְּנִיסָן וְלֹא לָוָה עַד תִּשְׁרֵי, וְאָתֵי לְמִטְרַף לָקוֹחוֹת שֶׁלֹּא כַּדִּין, אַמַּאי לֹא יַחֲזִיר?

The Gemara asks: If that is so, the following difficulty arises: How will one account for the ruling of the mishna here, which teaches that if the promissory notes include a property guarantee, the finder should not return them to the creditor; and we established that the reference is to a case when the debtor admits that he still owes the debt and that the promissory note should not be returned due to suspicion that perhaps the debtor wrote it with the intention to borrow the money in Nisan but did not actually borrow it until Tishrei, and therefore, if the promissory note is returned to the creditor he will come to repossess the land from the purchasers unlawfully. If Rav Asi’s explanation is correct, why shouldn’t the finder return the document?

נֶחְזֵי אִי בִּשְׁטַר הַקְנָאָה – הָא שַׁעְבֵּיד לֵיהּ נַפְשֵׁיהּ! אִי בִּשְׁטָר דְּלָא הַקְנָאָה – לֵיכָּא לְמֵיחַשׁ, דְּהָא אָמְרַתְּ כִּי לֵיכָּא מַלְוֶה בַּהֲדֵיהּ לָא כָּתְבִינַן.

The Gemara elaborates: Let us see what the possibilities are. If the reference is to a deed of transfer, didn’t the debtor obligate himself that his property can be collected for payment of the loan from the date that the deed of transfer was written? Conversely, if the reference is to a promissory note that is not a deed of transfer, there is no room for concern, as you said that in such a case, when the lender is not present together with the borrower, we do not write such a document.

אָמַר לְךָ רַב אַסִּי: אַף עַל גַּב דִּשְׁטָרֵי דְּלָאו הַקְנָאָה, כִּי לֵיכָּא מַלְוֶה בַּהֲדֵיהּ לָא כָּתְבִינַן, מַתְנִיתִין כֵּיוָן דִּנְפַל אִתְּרַע לֵיהּ, וְחָיְישִׁינַן דִּלְמָא אִקְּרִי וּכְתוּב.

The Gemara answers: Rav Asi could have said to you: Although we do not write promissory notes that are not deeds of transfer when the lender is not present together with the borrower, with regard to the case in the mishna it can be explained that since the promissory note was dropped, its credibility was compromised, and consequently we are concerned that perhaps it happened to have been written in the absence of the lender, deviating from the standard procedure.

אַבָּיֵי אָמַר: עֵדָיו בַּחֲתוּמָיו זָכִין לוֹ, וַאֲפִילּוּ שְׁטָרֵי דְּלָאו הַקְנָאָה.

Abaye stated an alternative explanation of the mishna that allows one to write a promissory note for a borrower in the absence of the lender: The document’s witnesses, with their signatures, acquire the lender’s lien on the borrower’s land on the lender’s behalf, despite the fact that the loan did not occur yet. And this applies even with regard to promissory notes that are not deeds of transfer.

מִשּׁוּם דְּקַשְׁיָא לֵיהּ: כֵּיוָן דְּאָמְרַתְּ בִּשְׁטָרֵי דְּלָאו הַקְנָאָה כִּי לֵיתֵיהּ לְמַלְוֶה בַּהֲדֵיהּ לָא כָּתְבִינַן, לֵיכָּא לְמֵיחַשׁ דְּאִקְּרִי וּכְתוּב.

Abaye offered this explanation because Rav Asi’s explanation was difficult for him; since you said with regard to promissory notes that are not deeds of transfer that we do not write them when the lender is not present together with the borrower, there is no reason for concern that perhaps in the case of a found promissory note it happened to be written in the lender’s absence.

אֶלָּא הָא דִּתְנַן: מָצָא גִּיטֵּי נָשִׁים וְשִׁחְרוּרֵי עֲבָדִים, דְּיָיתֵיקֵי, מַתָּנָה וְשׁוֹבָרִים – הֲרֵי זֶה לֹא יַחְזִיר, שֶׁמָּא כְּתוּבִים הָיוּ וְנִמְלַךְ עֲלֵיהֶם שֶׁלֹּא לִיתְּנָם. וְכִי נִמְלַךְ עֲלֵיהֶם מַאי הָוֵי? וְהָא אָמְרַתְּ: עֵדָיו בַּחֲתוּמָיו זָכִין לוֹ?

The Gemara asks: But how can Abaye’s opinion be reconciled with that which we learned in a mishna (18a): If one found bills of divorce, or bills of manumission of slaves, or wills [deyaitiki], or deeds of gift, or receipts, he may not return them to the people who are presumed to have lost them. The reason is that perhaps they were only written and not delivered, because the one who wrote them subsequently reconsidered about them and decided not to deliver them. The Gemara asks: If he reconsidered and decided not to deliver them, what of it? Didn’t you say that a document’s witnesses, with their signatures, acquire it on behalf of the recipient? If so, why shouldn’t it be returned to him?

הָנֵי מִילֵּי הֵיכָא דְּקָא מָטוּ לִידֵיהּ. אֲבָל הֵיכָא דְּלָא מָטוּ לִידֵיהּ לָא אָמְרִינַן.

The Gemara answers: This statement, that a creditor acquires the lien on the debtor’s land immediately when the witnesses sign the document, applies only in a case where the document came into the creditor’s possession; but in a case where the document did not come into his possession, as it was never given to him, we do not say that.

אֶלָּא מַתְנִיתִין דְּקָתָנֵי: מָצָא שִׁטְרֵי חוֹב, אִם יֵשׁ בָּהֶם אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים – לֹא יַחְזִיר. וְאוֹקִימְנָא כְּשֶׁחַיָּיב מוֹדֶה, וּמִשּׁוּם שֶׁמָּא כָּתַב לִלְוֹת בְּנִיסָן וְלֹא לָוָה עַד תִּשְׁרֵי.

The Gemara asks: Rather, how can the mishna be reconciled with Abaye’s opinion? As it teaches: With regard to one who found promissory notes, if they include a property guarantee, he may not return them to the creditor. And we established that the mishna is referring to a case when the liable party, i.e., the debtor, admits to the debts, and nevertheless the finder may not return the note due to the suspicion that perhaps he wrote the promissory note with the intention to borrow the money in Nisan but he did not actually borrow it until Tishrei.

בִּשְׁלָמָא לְרַב אַסִּי דְּאָמַר בִּשְׁטָרֵי אַקְנְיָיתָא – מוֹקֵי לַהּ בִּשְׁטָרֵי דְּלָאו אַקְנְיָיתָא, וְכִדְאָמְרִינַן. אֶלָּא לְאַבָּיֵי, דְּאָמַר: עֵדָיו בַּחֲתוּמָיו זָכִין לוֹ, מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר?

The Gemara elaborates: Granted, according to Rav Asi, who says that the halakha that a promissory note may be written for a borrower in the absence of the lender applies only with regard to deeds of transfer, the mishna can be established as referring to promissory notes that are not deeds of transfer, and it is as we stated above. But according to Abaye, who says that a document’s witnesses, with their signatures, acquire the lien on the lender’s behalf, what is there to say? Why shouldn’t one return the promissory notes even if they include a property guarantee for the loan?

אָמַר לָךְ אַבָּיֵי, מַתְנִיתִין הַיְינוּ טַעְמָא: דְּחָיְישִׁ[ינַן] לְפֵרָעוֹן וְלִקְנוּנְיָא.

The Gemara answers that Abaye could have said to you that this is the reason for the ruling in the mishna: It is that the tanna suspects that there was repayment and collusion. Although the debtor admits his debt, he is suspected to be lying, as after he repaid the debt he might have colluded with the creditor to repossess land that he sold during the period of the loan, and the debtor and creditor would split the money between them.

וְלִשְׁמוּאֵל, דְּאָמַר לָא חָיְישִׁינַן לְפֵרָעוֹן וְלִקְנוּנְיָא, מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר? הָנִיחָא אִי סָבַר לַהּ כְּרַב אַסִּי דְּאָמַר בִּשְׁטָרֵי הַקְנָאָה – מוֹקֵי מַתְנִיתִין בִּשְׁטָרֵי דְּלָאו הַקְנָאָה. אֶלָּא אִי סָבַר כְּאַבָּיֵי דְּאָמַר עֵדָיו בַּחֲתוּמָיו זָכִין לוֹ, מַאי אִיכָּא לְמֵימַר?

The Gemara asks: But according to Shmuel, who says that we do not suspect repayment and collusion, what is there to say? How can the mishna be explained? This works out well if Shmuel holds in accordance with the opinion of Rav Asi, who says that only in the case of deeds of transfer is it permitted to write a promissory note for a borrower in the absence of the lender. Accordingly, Shmuel can establish the mishna as referring to promissory notes that are not deeds of transfer. But if Shmuel holds in accordance with the opinion of Abaye, who says that a document’s witnesses, with their signatures, acquire the lien on the creditor’s behalf, what is there to say?

שְׁמוּאֵל מוֹקֵי לְמַתְנִיתִין כְּשֶׁאֵין חַיָּיב מוֹדֶה.

The Gemara answers: Shmuel can establish the mishna as referring to a case when the purported liable party does not admit to the debt, and therefore the finder may not return the promissory notes to the creditor.

אִי הָכִי, כִּי אֵין בָּהֶן אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים אַמַּאי יַחְזִיר? נְהִי דְּלָא גָּבֵי מִן מְשַׁעְבְּדֵי, מִבְּנֵי חָרֵי מִגְבֵּי גָּבֵי!

The Gemara asks: If so, in a case when the promissory notes do not include a property guarantee, why must the finder return them to the purported creditor? Granted, the creditor cannot collect the debt from liened property that had been sold, but he can collect it from the debtor’s unsold property, even though the debtor claims to be exempt.

שְׁמוּאֵל לְטַעְמֵיהּ: דְּאָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל, אוֹמֵר הָיָה רַבִּי מֵאִיר: שְׁטַר חוֹב שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים – אֵין גּוֹבֶה לָא מִמְּשַׁעְבְּדִי וְלָא מִבְּנֵי חָרֵי.

The Gemara answers: Shmuel conforms to his standard line of reasoning, as Shmuel says that Rabbi Meir would say: In the case of a promissory note that does not include a property guarantee, the creditor collects neither from liened property that has been sold nor from unsold property. Therefore, there is no harm in the finder returning the promissory note to the creditor.

וְכִי מֵאַחַר שֶׁאֵינוֹ גּוֹבֶה אַמַּאי יַחְזִיר? אָמַר רַבִּי נָתָן בַּר אוֹשַׁעְיָא: לָצוֹר עַל פִּי צְלוֹחִיתוֹ שֶׁל מַלְוֶה.

The Gemara asks: But since the creditor cannot collect the debt, why should the finder return the promissory note? For what purpose can the creditor use it? Rabbi Natan bar Oshaya says: The creditor can use it to cover the opening of his flask. Its only value is as a piece of paper.

וְנַהְדְּרֵיהּ (לְהוּ) לְלֹוֶה לָצוֹר עַל פִּי צְלוֹחִיתוֹ שֶׁל לֹוֶה! לֹוֶה הוּא

The Gemara asks: If the document has only the value of the paper, let the finder return it to the debtor, to cover the opening of the debtor’s flask. The Gemara answers: The debtor is

דְּאָמַר לֹא הָיוּ דְבָרִים מֵעוֹלָם.

the one who says that these matters, the loan, never happened and that the promissory note is forged. Therefore, he has no claim to the paper on which the promissory note is written.

אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר: מַחְלוֹקֶת בְּשֶׁאֵין חַיָּיב מוֹדֶה. דְּרַבִּי מֵאִיר סָבַר: שְׁטָר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים – אֵינוֹ גּוֹבֶה לָא מִמְּשַׁעְבְּדִי וְלָא מִבְּנֵי חָרֵי. וְרַבָּנַן סָבְרִי: מִמְּשַׁעְבְּדִי הוּא דְּלָא גָּבֵי, מִבְּנֵי חָרֵי – מִגְבָּא גָּבֵי. אֲבָל כְּשֶׁחַיָּיב מוֹדֶה – דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל יַחְזִיר, וְלָא חָיְישִׁינַן לְפֵרָעוֹן וְלִקְנוּנְיָא.

§ Rabbi Elazar says: The dispute in the mishna between Rabbi Meir and the Rabbis is in a case when the purported liable party does not admit to the debt. As, Rabbi Meir holds that with a promissory note that does not include a property guarantee, one can collect a debt neither from liened property that has been sold nor from unsold property. And the Rabbis hold that it is only from liened property that one cannot collect a debt using this promissory note but that one does collect a debt from unsold property. But in a case when the liable party admits to the debt, everyone agrees that the finder must return the promissory note, and we do not suspect the creditor and the debtor of engaging in repayment and collusion [veliknuneya] to the detriment of one who purchased land from the debtor.

וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: מַחְלוֹקֶת כְּשֶׁחַיָּיב מוֹדֶה, דְּרַבִּי מֵאִיר סָבַר: שְׁטָר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים – מִמְּשַׁעְבְּדִי הוּא דְּלָא גָּבֵי, אֲבָל מִבְּנֵי חָרֵי – מִגְבָּא גָּבֵי. וְרַבָּנַן סָבְרִי: מִמְּשַׁעְבְּדֵי נָמֵי גָּבֵי. אֲבָל כְּשֶׁאֵין חַיָּיב מוֹדֶה – דִּבְרֵי הַכֹּל לֹא יַחְזִיר, דְּחָיְישִׁינַן לְפֵרָעוֹן.

And Rabbi Yoḥanan says: The dispute is in a case when the liable party admits to the debt. As, Rabbi Meir holds that it is only from liened property that one cannot collect a debt using a promissory note that does not include a property guarantee, but one does collect a debt from unsold property. And the Rabbis hold that one collects a debt from liened property too. But in a case when the liable party does not admit to the debt, everyone agrees that the finder may not return the promissory note, as we suspect that perhaps there was repayment.

תַּנְיָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, וּתְיוּבְתָּא דְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בַּחֲדָא, וּתְיוּבְתָּא דִשְׁמוּאֵל בְּתַרְתֵּי.

It is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan, and from it there is also a conclusive refutation of one element of the opinion of Rabbi Elazar and a conclusive refutation of two elements of the opinion of Shmuel.

מָצָא שִׁטְרֵי חוֹב וְיֵשׁ בָּהֶם אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים, אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁשְּׁנֵיהֶם מוֹדִים – לֹא יַחְזִיר לֹא לָזֶה וְלֹא לָזֶה. אֵין בָּהֶן אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים, בִּזְמַן שֶׁהַלֹּוֶה מוֹדֶה – יַחְזִיר לַמַּלְוֶה, אֵין הַלֹּוֶה מוֹדֶה – לֹא יַחְזִיר לֹא לָזֶה וְלֹא לָזֶה, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר.

The baraita teaches: In a case where one found promissory notes and they include a property guarantee, even if both the creditor and the debtor agree about the existence of the debt, the finder should not return it to this creditor or to that debtor. If they do not include a property guarantee, then in a case when the debtor admits to the debt, one should return the promissory note to the creditor. But if the debtor does not admit to the debt, one should not return it to this creditor or to that debtor. This is the statement of Rabbi Meir.

שֶׁהָיָה רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: שְׁטָרי שֶׁיֵּשׁ (בָּהֶם) [בּוֹ] אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים, גּוֹבֶה מִנְּכָסִים מְשׁוּעְבָּדִים. וְשֶׁאֵין (בָּהֶם) [בּוֹ] אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים, גּוֹבֶה מִנְּכָסִים בְּנֵי חוֹרִין. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: אֶחָד זֶה וְאֶחָד זֶה גּוֹבֶה מִנְּכָסִים מְשׁוּעְבָּדִים.

The baraita continues: As Rabbi Meir would say: With promissory notes that include a property guarantee, one can collect the debt from liened property; but with those that do not include a property guarantee, one collects the debt only from unsold property. And the Rabbis say: With both this type and that type of promissory note, one can collect the debt from liened property.

תְּיוּבְתָּא דְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בַּחֲדָא, דְּאָמַר: לְרַבִּי מֵאִיר שְׁטָר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים – אֵינוֹ גּוֹבֶה מִנְּכָסִים מְשׁוּעְבָּדִים וְלֹא מִנְּכָסִים בְּנֵי חוֹרִין. וְקָאָמַר: בֵּין לְרַבִּי מֵאִיר בֵּין לְרַבָּנַן לָא חָיְישִׁינַן לִקְנוּנְיָא.

This is a conclusive refutation of one element of the opinion of Rabbi Elazar, who says that according to Rabbi Meir, with a promissory note that does not include a property guarantee one can collect a debt neither from liened property that has been sold nor from unsold property. And Rabbi Elazar also says that according to both Rabbi Meir and the Rabbis, we do not suspect that there is collusion between the debtor and the creditor.

וּבָרָיְיתָא קָתָנֵי: שְׁטָר שֶׁאֵין בּוֹ אַחְרָיוּת נְכָסִים – מִמְּשַׁעְבְּדִי הוּא דְּלָא גָּבֵי, הָא מִבְּנֵי חוֹרִין מִגְבָּא גָּבֵי. וְקָתָנֵי: בֵּין לְרַבִּי מֵאִיר בֵּין לְרַבָּנַן, חָיְישִׁינַן לִקְנוּנְיָא. דְּקָתָנֵי: אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁשְּׁנֵיהֶם מוֹדִים לֹא יַחְזִיר לֹא לָזֶה וְלֹא לָזֶה. אַלְמָא חָיְישִׁינַן לִקְנוּנְיָא.

And the baraita teaches that with a promissory note that does not include a property guarantee the creditor cannot collect a debt from liened property, but he can collect it from unsold property. And the baraita also teaches that according to the opinions of both Rabbi Meir and the Rabbis, we suspect that there is collusion between the debtor and the creditor, as it is taught that if one found promissory notes that include a property guarantee, even if both the creditor and the debtor agree about the existence of the debt, the finder should not return it to this creditor or to that debtor. Apparently, we suspect collusion. This refutes Rabbi Elazar’s opinion that there is no suspicion of collusion.

וְהָא הָנֵי תַּרְתֵּי הוּא?

The Gemara asks: But aren’t these two elements of Rabbi Elazar’s statement that are refuted by the baraita? Why was it stated above that only one element is refuted?