רוצה להקדיש לימוד?

חדשה בלימוד הגמרא?

זה הדף הראשון שלך? איזו התרגשות עצומה! יש לנו בדיוק את התכנים והכלים שיעזרו לך לעשות את הצעדים הראשונים ללמידה בקצב וברמה שלך, כך תוכלי להרגיש בנוח גם בתוך הסוגיות המורכבות ומאתגרות.

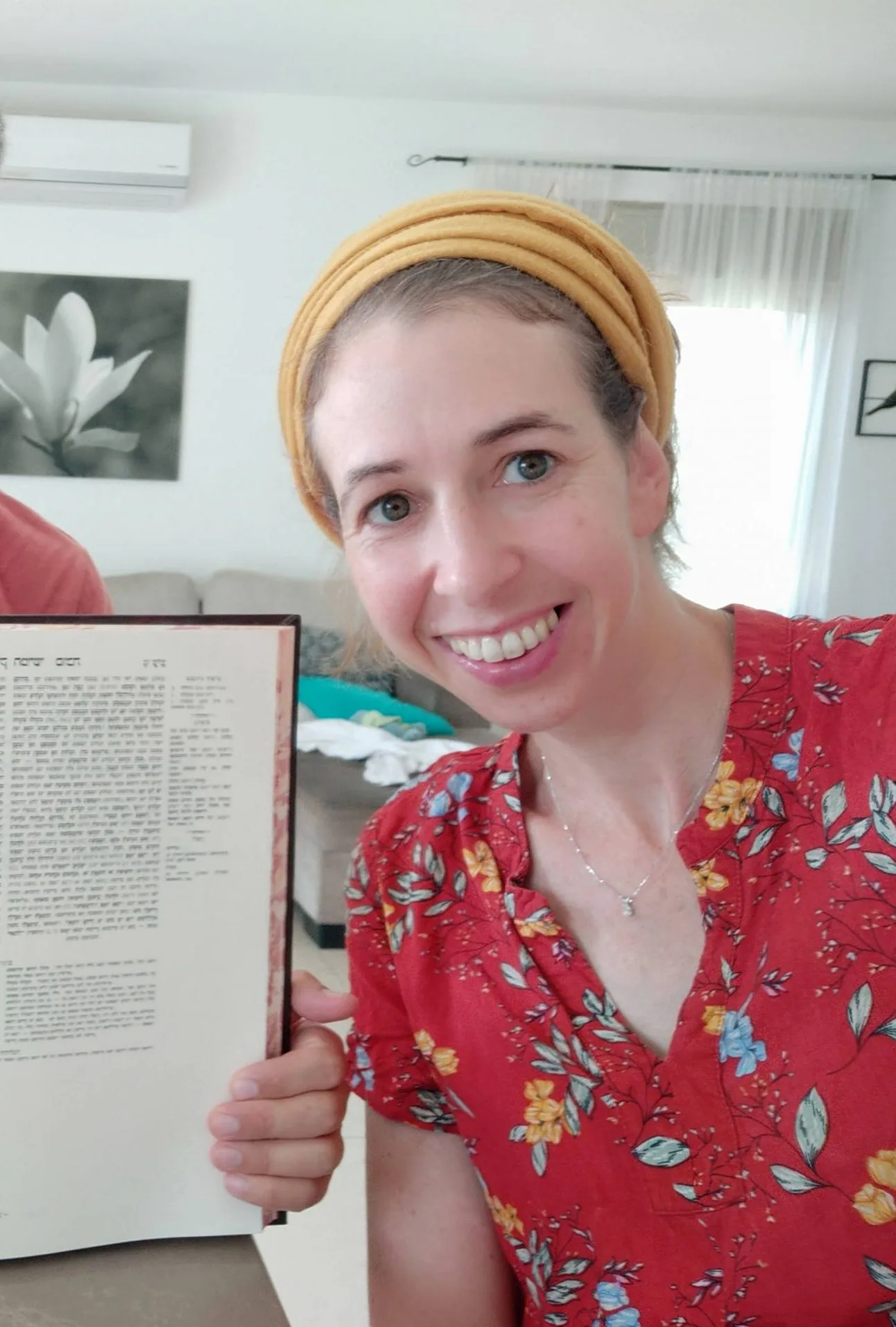

פסיפס הלומדות שלנו

גלי את קהילת הלומדות שלנו, מגוון נשים, רקעים וסיפורים. כולן חלק מתנועה ומסע מרגש ועוצמתי.

קידושין ו

לִישָּׁנֵי בָּתְרָאֵי קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן: הָכָא כְּתִיב ״כִּי יִקַּח״ – וְלֹא שֶׁיַּקַּח אֶת עַצְמוֹ. וְהָכָא כְּתִיב ״וְשִׁלְּחָהּ״ – וְלֹא שֶׁיְּשַׁלַּח אֶת עַצְמוֹ.

last expressions are what he teaches us. The novelty of Shmuel’s statement is that with regard to the second set of pronouncements there is no concern at all that a valid betrothal or divorce might have been performed. The Gemara explains why according to Shmuel these pronouncements are not of concern. Here, in the case of betrothal, it is written: “When a man takes a woman” (Deuteronomy 24:1), which indicates that the man is acting to change the status of the woman, and it is not written that he takes himself or gives himself to her, as in the case of one who says: I am hereby your man. And likewise, it is written here, with regard to divorce: “And sends her” (Deuteronomy 24:1), and it is not written that he sends himself from her, as in the case of one who says: I am not your man.

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ אִשְׁתִּי״, ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ אֲרוּסָתִי״, ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ קְנוּיָה לִי״ – מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת. ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ שֶׁלִּי״, ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ בִּרְשׁוּתִי״, ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ זְקוּקָה לִי״ – מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת. וְלִיתְנִינְהוּ כּוּלְּהוּ כַּחֲדָא! תַּנָּא תְּלָת תְּלָת, שַׁמְעִינְהוּ וְגַרְסִינְהוּ.

The Sages taught in a baraita that if a man says to a woman: You are hereby my wife, or: You are hereby my betrothed, or: You are hereby acquired to me, then she is betrothed. If he said to her: You are hereby mine, or: You are hereby under my authority, or: You are hereby bound to me, then she is betrothed. The Gemara asks: But as the halakha is that she is betrothed with regard to both sets of statements, let the baraita teach all of them together. Why does the baraita divide these statements into two groups? The Gemara answers: The tanna heard them as two sets of three, and consequently he taught them in that form. He heard each sequence of three cases as a separate halakha from his teachers, and therefore he preserved them as two sets of three.

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: ״מְיוּחֶדֶת לִי״ מַהוּ? ״מְיוֹעֶדֶת לִי״ מַהוּ? ״עֶזְרָתִי״ מַהוּ? ״נֶגְדָּתִי״ מַהוּ? ״עֲצוּרָתִי״ מַהוּ? ״צַלְעָתִי״ מַהוּ? ״סְגוּרָתִי״ מַהוּ? ״תַּחְתַּי״ מַהוּ? ״תְּפוּשָׂתִי״ מַהוּ? ״לְקוּחָתִי״ מַהוּ?

A dilemma was raised before the Sages: If a man betrothing a woman said: You are hereby unique to me, what is the halakha? Is this woman betrothed? Similarly, if he said to her: You are hereby designated to me, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby my helper, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby my counterpart, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby my gathered one, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby my rib, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby my closed one, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby beneath me, what is the halakha? If he said: You are hereby my seized one, what is the halakha? Finally, if he said: You are hereby my taken one, what is the halakha?

פְּשׁוֹט מִיהָא חֲדָא, דְּתַנְיָא: הָאוֹמֵר ״לְקוּחָתִי״ – הֲרֵי זוֹ מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, מִשּׁוּם ״שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר כִּי יִקַּח אִישׁ אִשָּׁה״.

The Gemara suggests: Resolve at least one of these dilemmas, as it is taught in a baraita: With regard to one who says to a woman: You are hereby my taken one, she is betrothed, because it is stated: “When a man takes a woman” (Deuteronomy 24:1).

אִיבַּעְיָא לְהוּ: ״חֲרוּפָתִי״ מַהוּ? תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּתַנְיָא: הָאוֹמֵר ״חֲרוּפָתִי״ – מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, שֶׁכֵּן בִּיהוּדָה קוֹרִין לָאֲרוּסָה ״חֲרוּפָה״. וִיהוּדָה הָוְיָא רוּבָּא דְּעָלְמָא?

A dilemma was raised before the Sages: If a man says to a woman: You are hereby my espoused one [ḥarufati], what is the halakha? Come and hear, as it is taught in a baraita that with regard to one who says: You are hereby my espoused one, she is betrothed, as in Judea they call a betrothed woman a ḥarufa, an espoused woman. The Gemara asks: And is Judea most of the world? Even if this is true in Judea, why should a halakha that applies in all locations be based on this local custom?

הָכִי קָאָמַר: הָאוֹמֵר ״חֲרוּפָתִי״ – מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְהִיא שִׁפְחָה נֶחֱרֶפֶת לְאִישׁ״. וְעוֹד, בִּיהוּדָה קוֹרִין לָאֲרוּסָה ״חֲרוּפָה״. וִיהוּדָה וְעוֹד לִקְרָא? אֶלָּא הָכִי קָאָמַר: הָאוֹמֵר ״חֲרוּפָה״ בִּיהוּדָה – מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, שֶׁכֵּן בִּיהוּדָה קוֹרִין לָאֲרוּסָה ״חֲרוּפָה״.

The Gemara answers that this is what the baraita is saying: With regard to one who says: You are hereby my espoused one, she is betrothed, as it is stated: “Who is a maidservant espoused [neḥerefet] to a man” (Leviticus 19:20). This verse means that she is betrothed to a certain man. And furthermore, the baraita adds another proof for this claim: In Judea they call a betrothed woman a ḥarufa, an espoused woman. The Gemara asks: And is it reasonable to introduce the custom in Judea with the term: And furthermore, as proof to a halakha derived from a verse? Rather, the Gemara explains that this is what the baraita is saying: With regard to one who says: You are hereby espoused, in Judea, she is betrothed, as in Judea they call a betrothed woman a ḥarufa, an espoused woman.

בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן? אִילֵימָא בְּשֶׁאֵין מְדַבֵּר עִמָּהּ עַל עִסְקֵי גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ – מְנָא יָדְעָה מַאי קָאָמַר לַהּ? וְאֶלָּא בִּמְדַבֵּר עִמָּהּ עַל עִסְקֵי גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ – אַף עַל גַּב דְּלָא אָמַר לָהּ נָמֵי,

The Gemara asks a general question with regard to all the previously mentioned expressions: With what are we dealing? If we say that these dilemmas are referring to a case where he was not speaking with her about matters of her bill of divorce or her betrothal, but suddenly issued this statement to her, from where does she know what he is saying to her? Out of context, these statements are not necessarily referring to betrothal. Rather, they are referring to a case where he was speaking to her about matters of her bill of divorce and her betrothal. But if so, even though he did not say anything, she would also be betrothed if he gave her money for the purpose of betrothal.

דִּתְנַן: הָיָה מְדַבֵּר עִם אִשָּׁה עַל עִסְקֵי גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ, וְנָתַן לָהּ גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ וְלֹא פֵּירֵשׁ – רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: דַּיּוֹ. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: צָרִיךְ לְפָרֵשׁ. וְאָמַר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי!

As we learned in a mishna (Ma’aser Sheni 4:7): If one was speaking with a woman about matters of her bill of divorce or her betrothal, and he gave her a bill of divorce or her betrothal, i.e., the money or a document of betrothal, but did not clarify his action, Rabbi Yosei says: This is sufficient for him, i.e., it is a valid divorce or betrothal because she will understand his intention from the context. Rabbi Yehuda says: He is required to clarify the meaning of his behavior. And Rav Huna says that Shmuel says: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei. If so, even if he said nothing to her she would still be betrothed, and this should certainly be the case if he says one of the statements under discussion.

אָמְרִי: לְעוֹלָם בִּמְדַבֵּר עִמָּהּ עַל עִסְקֵי גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ, וְאִי דְּיָהֵיב לַהּ וְשָׁתֵיק הָכִי נָמֵי, הָכָא בְּמַאי עָסְקִינַן דִּיהַב לַהּ וַאֲמַר לַהּ בְּהָנֵי לִישָּׁנֵי,

The Sages say in explanation of this matter: Actually, we are dealing with cases where he was speaking to her about matters of her bill of divorce and her betrothal, and if it was referring to a case where he had given her the money and been silent, so too it would have been a valid betrothal. With what are we dealing here? This is a case where he gave her something and said to her one of these expressions.

וְהָכִי קָא מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ: הָנֵי לִישָּׁנֵי לְקִידּוּשֵׁי קָאָמַר לַהּ, אוֹ דִילְמָא לִמְלָאכָה קָאָמַר לַהּ? תֵּיקוּ.

And this is the dilemma raised before the Sages: These expressions, did he say them to her for the purpose of betrothal, or perhaps he said them to her for the purpose of labor? He might have intended to hire her, withdrawing his previous intention to betroth her. In other words, his statement in conjunction with his giving of an item renders the meaning of the expression less clear than if he had remained silent. The Gemara leaves most of these issues unanswered, and states that the dilemmas shall stand unresolved.

גּוּפָא: הָיָה מְדַבֵּר עִם הָאִשָּׁה עַל עִיסְקֵי גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ, וְנָתַן לָהּ גִּיטָּהּ וְקִידּוּשֶׁיהָ וְלֹא פֵּירֵשׁ – רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: דַּיּוֹ. רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: צָרִיךְ לְפָרֵשׁ. אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: וְהוּא שֶׁעֲסוּקִין בְּאוֹתוֹ עִנְיָן.

§ The Gemara discusses the matter itself: If he was speaking to the woman about matters of her bill of divorce or her betrothal, and he gave her bill of divorce or her betrothal to her and did not clarify his intention, Rabbi Yosei says: This is sufficient for him. Rabbi Yehuda says: He is required to clarify. Rav Yehuda says that Shmuel says: And this is the halakha provided that they were discussing the same issue and had not moved on to a different topic.

וְכֵן אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר אָמַר רַבִּי אוֹשַׁעְיָא: וְהוּא שֶׁעֲסוּקִין בְּאוֹתוֹ עִנְיָן. כְּתַנָּאֵי: רַבִּי אוֹמֵר: וְהוּא שֶׁעֲסוּקִין בְּאוֹתוֹ עִנְיָן. רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בַּר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר: אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁאֵין עֲסוּקִין בְּאוֹתוֹ עִנְיָן.

And likewise, Rabbi Elazar says that Rabbi Oshaya says: And this is the halakha provided that they were discussing the same issue. The Gemara comments: This disagreement is like a dispute between tanna’im on this topic. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi says: And this is the halakha provided that they were discussing the same issue. Rabbi Elazar bar Rabbi Shimon says: This is the halakha despite the fact that they were not discussing the same issue.

וְאִי לָאו דַּעֲסוּקִין בְּאוֹתוֹ עִנְיָן, מְנָא יָדְעָה מַאי קָאָמַר לַהּ? אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: מֵעִנְיָן לְעִנְיָן בְּאוֹתוֹ עִנְיָן.

The Gemara asks: And if they were not discussing the same issue, from where does she know what he is saying to her? They have already changed the topic of conversation, and these expressions on their own are ambiguous. Abaye said: They have not changed to an entirely different topic; rather, they changed from discussing one topic to discussing another topic within the same general topic. In other words, they were no longer speaking directly about divorce or betrothal, but they were still discussing related matters. Therefore, his intention was clear to her when he made his statement.

אָמַר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב יֵימַר לְרַב אָשֵׁי: וְאֶלָּא הָא דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: כׇּל שֶׁאֵינוֹ יוֹדֵעַ בְּטִיב גִּיטִּין וְקִידּוּשִׁין לֹא יְהֵא לוֹ עֵסֶק עִמָּהֶם, אֲפִילּוּ לָא שְׁמִיעַ לֵיהּ הָא דְּרַב הוּנָא אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל? אֲמַר לֵיהּ: אִין, הָכִי נָמֵי.

Rav Huna says that Shmuel says: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei. Rav Yeimar said to Rav Ashi: But if so, with regard to that which Rav Yehuda says that Shmuel says: Anyone who does not know the nature of bills of divorce and betrothals should have no dealings in them, i.e., he may not serve as a judge in cases of this kind lest he permit that which is prohibited, does this principle apply even if that individual did not hear this halakha that Rav Huna says that Shmuel says? Since this type of case is uncommon, should such an individual be considered unfamiliar with the halakhot of bills of divorce and betrothals? Rav Ashi said to him: Yes, it is indeed so; this person is considered to lack the requisite knowledge to deal with these cases. This ruling is an important matter with regard to the halakhot of betrothal, and one who is unaware of it might err.

וְכֵן בְּגֵירוּשִׁין, נָתַן לָהּ גִּיטָּהּ וְאָמַר לָהּ: ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ מְשׁוּלַּחַת״ ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ מְגוֹרֶשֶׁת״, ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ מוּתֶּרֶת לְכׇל אָדָם״ – הֲרֵי הִיא מְגוֹרֶשֶׁת. פְּשִׁיטָא נָתַן לָהּ גִּיטָּהּ, וְאָמַר לָהּ לְאִשְׁתּוֹ: ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ בַּת חוֹרִין״

The Gemara returns to Shmuel’s statement. And similarly, with regard to divorce: If a husband gave his wife her bill of divorce and said to her: You are hereby sent away, or: You are hereby divorced, or: You are hereby permitted to marry any man, then she is divorced. The Gemara comments: It is obvious that if a husband gave her a bill of divorce and said to his wife: You are hereby a free woman,

– לֹא אָמַר וְלֹא כְּלוּם. אָמַר לָהּ לְשִׁפְחָתוֹ: ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ מוּתֶּרֶת לְכׇל אָדָם״ – לֹא אָמַר וְלֹא כְּלוּם.

he has said nothing, as this statement is not a valid expression of divorce. Similarly, if a master said to his female Canaanite slave upon emancipating her: You are hereby permitted to any man, he has not said anything.

אָמַר לָהּ לְאִשְׁתּוֹ: ״הֲרֵי אַתְּ לְעַצְמְךָ״ מַהוּ? מִי אָמְרִינַן לִמְלָאכָה קָאָמַר לַהּ, אוֹ דִילְמָא לִגְמָרֵי קָאָמַר לַהּ?

The Gemara addresses a less straightforward case: If a man said to his wife: You are hereby for yourself, what is the halakha? Do we say that he said this to her only with regard to work? In other words, he might have meant that she may keep her earnings. Or perhaps he said to her that she is on her own entirely, i.e., she is divorced.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבִינָא לְרַב אָשֵׁי: תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּתַנְיָא: גּוּפוֹ שֶׁל גֵּט שִׁחְרוּר: ״הֲרֵי אַתָּה בֶּן חוֹרִין״, ״הֲרֵי אַתָּה לְעַצְמְךָ״. הַשְׁתָּא וּמָה עֶבֶד כְּנַעֲנִי דִּקְנֵי לֵיהּ גּוּפֵיהּ, כִּי אָמַר לֵיהּ ״הֲרֵי אַתָּה לְעַצְמְךָ״ – לִגְמָרֵי קָאָמַר לֵיהּ, אִשָּׁה דְּלָא קְנֵי לֵיהּ גּוּפַהּ, לֹא כׇּל שֶׁכֵּן?

Ravina said to Rav Ashi: Come and hear a proof, as it is taught in a baraita: The essence of a bill of manumission is the expression: You are hereby a freeman, or: You are hereby for yourself. Now consider, if in the case of a Canaanite slave, whose body belongs to the master, even so, when the master says to him: You are hereby for yourself, this is considered as though he said to him that he is entirely on his own and is freed, then all the more so is it not clear that a wife, whose body is not owned by her husband, is divorced by means of this expression?

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבִינָא לְרַב אָשֵׁי: אָמַר לְעַבְדּוֹ ״אֵין לִי עֵסֶק בְּךָ״ מַאי? מִי אָמְרִינַן ״אֵין לִי עֵסֶק בְּךָ״ – לִגְמָרֵי קָאָמַר לֵיהּ, אוֹ דִילְמָא לִמְלָאכָה קָאָמַר לֵיהּ?

With regard to the same issue, Ravina said to Rav Ashi: If one said to his Canaanite slave: I have no business with you, what is the halakha? Do we say that when he said to him: I have no business with you, he meant entirely, and therefore the slave is freed? Or did he perhaps say this to him with regard to labor? In other words, it is possible that the master is relieving the slave of his obligation to perform labor without actually emancipating him from slavery.

אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב נַחְמָן לְרַב אָשֵׁי וְאָמְרִי לַהּ רַב חָנִין מָחוֹזָאָה לְרַב אָשֵׁי: תָּא שְׁמַע: הַמּוֹכֵר עַבְדּוֹ לְנׇכְרִי – יָצָא לְחֵירוּת, וְצָרִיךְ גֵּט שִׁחְרוּר מֵרַבּוֹ רִאשׁוֹן.

Rav Naḥman said to Rav Ashi, and some say Rav Ḥanin from Meḥoza said to Rav Ashi: Come and hear: With regard to one who sells his Canaanite slave to a gentile, the slave is emancipated but nevertheless requires a bill [get] of manumission from his first master. In this manner the Sages penalized this owner for preventing the slave from fulfilling the mitzvot in which he is obligated.

אָמַר רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל: בַּמֶּה דְּבָרִים אֲמוּרִים – שֶׁלֹּא כָּתַב עָלָיו אוֹנוֹ, אֲבָל כָּתַב עָלָיו אוֹנוֹ – זֶהוּ שִׁחְרוּרוֹ. הֵיכִי דָּמֵי אוֹנוֹ? אָמַר רַב שֵׁשֶׁת: דִּכְתַב לֵיהּ: כְּשֶׁתִּבְרַח מִמֶּנּוּ – ״אֵין לִי עֵסֶק בְּךָ״.

Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel says in addition to this: In what case is this statement said? This is referring to a situation where he did not write a document [ono] for the slave when he sold him to the gentile. But if he wrote a document for him, this itself is his emancipation. The Gemara asks: What are the circumstances of this document? Rav Sheshet said that he writes to him: When you escape from him I have no business with you. This indicates that the formula: I have no business with you, is a valid expression of emancipation.

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: הַמְקַדֵּשׁ בְּמִלְוֶה – אֵינָהּ מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת. בַּהֲנָאַת מִלְוֶה – מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, וְאָסוּר לַעֲשׂוֹת כֵּן מִפְּנֵי הַעֲרָמַת רִבִּית.

§ Abaye says: With regard to one who betroths a woman with a loan, i.e., he previously lent this woman money and he now says that she is betrothed to him by means of that loan, she is not betrothed. The reason is that a woman can be betrothed only through her acceptance of money, or an item that has monetary value, at the time of the betrothal. Although this woman owes the man money, at the time the man states that she is betrothed to him, the loan is not in fact money but an obligation. Therefore, he does not actually give her anything at the time of the betrothal. By contrast, if he betroths her by means of the benefit of the loan, she is betrothed. But it is prohibited to do so, due to the fact that betrothing a woman via the benefit of a loan is an artifice used to circumvent the prohibition of receiving interest, as this enables the husband to gain an additional benefit from the loan.

הַאי הֲנָאַת מִלְוֶה, הֵיכִי דָמֵי? אִילֵּימָא דְּאַזְקְפַהּ, דַּאֲמַר לַהּ אַרְבַּע בְּחַמְשָׁה – הָא רִבִּית מְעַלַּיְיתָא הוּא. וְעוֹד, הַיְינוּ מִלְוֶה!

The Gemara clarifies: What is meant by this term: The benefit of the loan? If we say that it means that he established interest upon it when she took the loan, e.g., he said to her that he is lending her four coins in exchange for the repayment of five, and he betroths her by releasing her from the obligation to pay this additional coin, this is a case of full-fledged interest, not merely an artifice used to circumvent the prohibition of receiving interest. He is receiving full payment of the loan and an additional benefit. And furthermore, when he releases her from the obligation to pay this additional coin, he is simply forgoing another obligation she has toward him; he is not giving her anything. This is like a regular case of a betrothal with a loan, and therefore she should not be betrothed.

לָא צְרִיכָא, דְּאַרְוַוח לַהּ זִימְנָא.

The Gemara answers: No, it is necessary in a case where he extended the time of the loan for her. When the time for her to repay the loan arrived he extended the deadline and betrothed her with the financial benefit she receives from the extra time he is giving her to use the money. In this case he does betroth her with the value he is giving her at that time, but it is similar to interest, as it is included in the prohibition of interest to pay the creditor for an extension of the time of a loan.

אָמַר רָבָא: ״הֵילָךְ מָנֶה עַל מְנָת שֶׁתַּחֲזִירֵהוּ לִי״ בְּמֶכֶר – לֹא קָנָה, בְּאִשָּׁה – אֵינָהּ מְקוּדֶּשֶׁת, בְּפִדְיוֹן הַבֵּן – אֵין בְּנוֹ פָּדוּי,

§ Rava says: With regard to one who says to another: Here are one hundred dinars for you that I am giving you on the condition that you return them to me, if he gave these one hundred dinars as part of a purchase, he does not acquire the item, as he has not given the seller any money. And similarly, with regard to a woman, if he gave her money for her betrothal on the condition that she return it, she is not betrothed. If one gave money in this manner for the redemption of his firstborn son, for which a priest must receive five sela, his son is not redeemed.

בִּתְרוּמָה – יָצָא יְדֵי נְתִינָה. וְאָסוּר לַעֲשׂוֹת כֵּן, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁנִּרְאֶה כְּכֹהֵן הַמְסַיֵּיעַ בְּבֵית הַגְּרָנוֹת.

If one does this with regard to teruma, i.e., he gives produce to a priest as teruma on the condition that it will be returned, he has technically fulfilled his obligation of giving. Once he gets the teruma back it belongs to him, as he is the original owner, and although it is prohibited for him to partake of it, as he is a non-priest, he may sell it to a different priest. But it is prohibited to do this, i.e., give teruma in this manner, ab initio, because this priest receiving the teruma appears like a priest who assists at the threshing floor, as he presumably agrees to this arrangement in return for some gain.

מַאי קָסָבַר רָבָא? אִי קָסָבַר מַתָּנָה עַל מְנָת לְהַחֲזִיר שְׁמָהּ מַתָּנָה – אֲפִילּוּ כּוּלְּהוּ נָמֵי, וְאִי קָסָבַר לֹא שְׁמָהּ מַתָּנָה – אֲפִילּוּ תְּרוּמָה נָמֵי לָא.

The Gemara asks: What does Rava maintain? If he maintains that a gift given on the condition that it is returned is called a gift, this should apply not only to teruma but even to all the other cases, i.e., it should be considered a valid gift in all of the above cases. And if he maintains that a gift of this kind is not called a gift, then even with regard to teruma it should not be considered a legitimate form of giving.

וְעוֹד, הָא רָבָא הוּא דְּאָמַר: מַתָּנָה עַל מְנָת לְהַחֲזִיר שְׁמָהּ מַתָּנָה! דְּאָמַר רָבָא: ״הֵילָךְ אֶתְרוֹג זֶה עַל מְנָת שֶׁתַּחְזִירֵהוּ לִי״ – נְטָלוֹ וְהֶחְזִירוֹ – יָצָא. וְאִם לָאו – לֹא יָצָא!

And furthermore, Rava is the one who says: A gift given on the condition that it is later returned is called a gift. As Rava said that if one says to another on the first day of the festival of Sukkot: Take this etrog on the condition that you return it to me, and the recipient takes it, recites a blessing over it, and returns it, he has fulfilled his obligation, despite the fact that one must own the etrog he uses for the mitzva on the first day of Sukkot. And if he does not return it he has not fulfilled his obligation, as he gave him the gift only on the condition that it would be returned. This indicates that in the opinion of Rava, a gift that is given on the condition that it is returned is considered a gift.

אֶלָּא אָמַר רַב אָשֵׁי: בְּכוּלְּהוּ קָנֵי לְבַר מֵאִשָּׁה, לְפִי שֶׁאֵין אִשָּׁה נִקְנֵית בַּחֲלִיפִין. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב הוּנָא מָר בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב נְחֶמְיָה לְרַב אָשֵׁי: הָכִי אָמְרִינַן מִשְּׁמֵיהּ דְּרָבָא כְּווֹתָיךְ.

Rather, Rav Ashi said: In all of these cases the gift is acquired, except for the betrothal of a woman, because a woman cannot be acquired by means of symbolic exchange. Rav Huna Mar, son of Rav Neḥemya, said to Rav Ashi: We say this in the name of Rava in accordance with your opinion, not in accordance with the previous ruling.

אָמַר רָבָא: ״תֵּן מָנֶה לִפְלוֹנִי

§ Rava says that if a woman said to a man: Give one hundred dinars to so-and-so