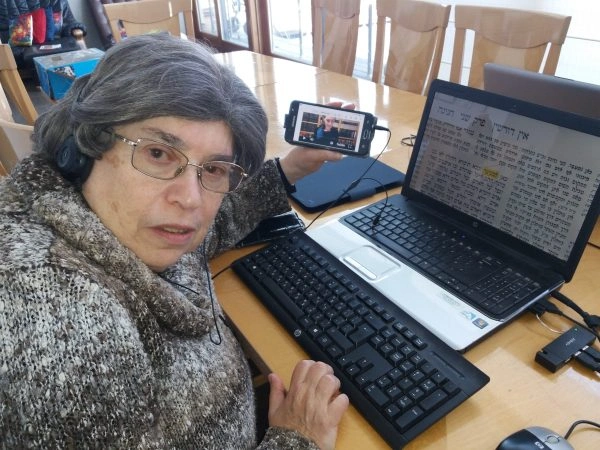

Bava Batra 2

הַשּׁוּתָּפִין שֶׁרָצוּ לַעֲשׂוֹת מְחִיצָה בְּחָצֵר – בּוֹנִין אֶת הַכּוֹתֶל בְּאֶמְצַע. מָקוֹם שֶׁנָּהֲגוּ לִבְנוֹת גְּוִיל, גָּזִית, כְּפִיסִין, לְבֵינִין – בּוֹנִין; הַכֹּל כְּמִנְהַג הַמְּדִינָה.

MISHNA: Partners who wished to make a partition [meḥitza] in a jointly owned courtyard build the wall for the partition in the middle of the courtyard. What is this wall fashioned from? In a place where it is customary to build such a wall with non-chiseled stone [gevil], or chiseled stone [gazit], or small bricks [kefisin], or large bricks [leveinim], they must build the wall with that material. Everything is in accordance with the regional custom.

גְּוִיל – זֶה נוֹתֵן שְׁלֹשָׁה טְפָחִים, וְזֶה נוֹתֵן שְׁלֹשָׁה טְפָחִים. בַּגָּזִית – זֶה נוֹתֵן טִפְחַיִים וּמֶחֱצָה וְזֶה נוֹתֵן טִפְחַיִים וּמֶחֱצָה. בַּכְּפִיסִין – זֶה נוֹתֵן טִפְחַיִים וְזֶה נוֹתֵן טִפְחַיִים. בִּלְבֵינִין – זֶה נוֹתֵן טֶפַח וּמֶחֱצָה וְזֶה נוֹתֵן טֶפַח וּמֶחֱצָה. לְפִיכָךְ, אִם נָפַל הַכּוֹתֶל – הַמָּקוֹם וְהָאֲבָנִים שֶׁל שְׁנֵיהֶם.

If they build the wall with non-chiseled stone, this partner provides three handbreadths of his portion of the courtyard and that partner provides three handbreadths, since the thickness of such a wall is six handbreadths. If they build the wall with chiseled stone, this partner provides two and a half handbreadths and that partner provides two and a half handbreadths, since such a wall is five handbreadths thick. If they build the wall with small bricks, this one provides two handbreadths and that one provides two handbreadths, since the thickness of such a wall is four handbreadths. If they build with large bricks, this one provides one and a half handbreadths and that one provides one and a half handbreadths, since the thickness of such a wall is three handbreadths. Therefore, if the wall later falls, the assumption is that the space where the wall stood and the stones belong to both of them, to be divided equally.

וְכֵן בַּגִּינָּה – מְקוֹם שֶׁנָּהֲגוּ לִגְדּוֹר – מְחַיְּיבִין אוֹתוֹ. אֲבָל בַּבִּקְעָה – מְקוֹם שֶׁנָּהֲגוּ שֶׁלֹּא לִגְדּוֹר – אֵין מְחַיְּיבִין אוֹתוֹ,

And similarly with regard to a garden, in a place where it is customary to build a partition in the middle of a garden jointly owned by two people, and one of them wishes to build such a partition, the court obligates his neighbor to join in building the partition. But with regard to an expanse of fields [babbika], in a place where it is customary not to build a partition between two people’s fields, and one person wishes to build a partition between his field and that of his neighbor, the court does not obligate his neighbor to build such a partition.

אֶלָּא אִם רָצָה, כּוֹנֵס לְתוֹךְ שֶׁלּוֹ וּבוֹנֶה, וְעוֹשֶׂה חֲזִית מִבַּחוּץ. לְפִיכָךְ, אִם נָפַל הַכּוֹתֶל – הַמָּקוֹם וְהָאֲבָנִים שֶׁלּוֹ.

Rather, if one person wishes to erect a partition, he must withdraw into his own field and build the partition there. And he makes a border mark on the outer side of the barrier facing his neighbor’s property, indicating that he built the entire structure of his own materials and on his own land. Therefore, if the wall later falls, the assumption is that the space where the wall stood and the stones belong only to him, as is indicated by the mark on the wall.

אִם עָשׂוּ מִדַּעַת שְׁנֵיהֶם – בּוֹנִין אֶת הַכּוֹתֶל בָּאֶמְצַע, וְעוֹשִׂין חֲזִית מִכָּאן וּמִכָּאן. לְפִיכָךְ, אִם נָפַל הַכּוֹתֶל – הַמָּקוֹם וְהָאֲבָנִים שֶׁל שְׁנֵיהֶם.

Nevertheless, in a place where it is not customary to build a partition between two people’s fields, if they made such a partition with the agreement of the two of them, they build it in the middle, i.e., on the property line, and make a border mark on the one side and on the other side. Therefore, if the wall later falls, the assumption is that the space where the wall stood and the stones belong to both of them, to be divided equally.

גְּמָ׳ סַבְרוּהָ מַאי ״מְחִיצָה״ – גּוּדָּא; כִּדְתַנְיָא: מְחִיצַת הַכֶּרֶם שֶׁנִּפְרְצָה, אוֹמֵר לוֹ: ״גְּדוֹר״. חָזְרָה וְנִפְרְצָה – אוֹמֵר לוֹ: ״גְּדוֹר״.

GEMARA: The Sages initially assumed: What is the meaning of the term meḥitza mentioned in the mishna? It means a partition, as it is taught in a baraita: Consider the case where a partition of [meḥitzat] a vineyard which separates the vineyard from a field of grain was breached, resulting, if the situation is not rectified, in the grain and grapes becoming items from which deriving benefit is prohibited due to the prohibition of diverse kinds planted in a vineyard. The owner of the field of grain may say to the owner of the vineyard: Build a partition between the vineyard and the field of grain. If the owner of the vineyard did so, and the partition was breached again, the owner of the field of grain may say to him again: Build a partition.

נִתְיָאֵשׁ הֵימֶנָּה וְלֹא גְּדָרָהּ – הֲרֵי זֶה קִידֵּשׁ, וְחַיָּיב בְּאַחְרָיוּתָהּ.

If the owner of the vineyard neglected to make the necessary repairs and did not properly build a partition between the fields, the grain and grapes are rendered forbidden due to the prohibition of diverse kinds planted in a vineyard, and he is liable for the monetary loss. He must compensate the owner of the grain for the damage suffered, as it is the vineyard owner’s fault that deriving benefit from the grain is now prohibited.

טַעְמָא דְּרָצוּ, הָא לֹא רָצוּ – אֵין מְחַיְּיבִין אוֹתוֹ; אַלְמָא הֶיזֵּק רְאִיָּה לָאו שְׁמֵיהּ הֶיזֵּק.

According to the understanding that the term meḥitza means a partition, one can infer: The reason that they build a wall is that they both wished to make a partition in their jointly owned courtyard. But if they did not both wish to do so, the court does not obligate the reluctant partner to build such a wall, although his neighbor objects to the fact that the partner can see what he is doing in his courtyard. Apparently, it may be concluded that damage caused by sight, that is, the discomfort suffered by someone because he is exposed to the gaze of others while he is in his own private domain, is not called damage.

וְאֵימָא ״מְחִיצָה״ – פְּלוּגְתָּא, כְּדִכְתִיב: ״וַתְּהִי מֶחֱצַת הָעֵדָה״; וְכֵיוָן דְּרָצוּ – בּוֹנִין אֶת הַכּוֹתֶל בְּעַל כׇּרְחוֹ, אַלְמָא הֶיזֵּק רְאִיָּה שְׁמֵיהּ הֶיזֵּק!

The Gemara objects to this conclusion: But say that the term meḥitza used in the mishna means a division, as it is written: “And the division of [meḥetzat] the congregation was” (Numbers 31:43), referring to the half of the spoil that belonged to the entire congregation. According to this interpretation the mishna means: Since they wished to divide the jointly owned courtyard, they build a proper wall in the center even against the will of one of the partners. Apparently, it may be concluded that damage caused by sight is called damage.

אִי הָכִי, הַאי ״שֶׁרָצוּ לַעֲשׂוֹת מְחִיצָה״?! ״שֶׁרָצוּ לַחֲצוֹת״ מִבְּעֵי לֵיהּ! אֶלָּא מַאי – גּוּדָּא? ״בּוֹנִין אֶת הַכּוֹתֶל״?! ״בּוֹנִין אוֹתוֹ״ מִבְּעֵי לֵיהּ! אִי תְּנָא ״אוֹתוֹ״, הֲוָה אָמֵינָא בִּמְסִיפָס בְּעָלְמָא, קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן כּוֹתֶל.

The Gemara rejects this line of reasoning: If it is so that the term meḥitza means a division, the words: Who wished to make a division, are imprecise, as the tanna should have said: Who wished to divide. Rather, what is the meaning of the term meḥitza? A partition. The Gemara retorts: If so, the words: They build the wall, are imprecise, as the tanna should have said: They build it, since the wall and the partition are one and the same. The Gemara responds: Had the tanna taught: They build it, I would say that a mere partition of pegs [bimseifas] would suffice. He therefore teaches us that they build an actual wall, all in accordance with the regional custom.

בּוֹנִין אֶת הַכּוֹתֶל בָּאֶמְצַע וְכוּ׳. פְּשִׁיטָא!

The mishna teaches: Partners who wished to make a partition in a jointly owned courtyard build the wall for the partition in the middle of the courtyard. The Gemara asks: Isn’t it obvious that if they agree to build a wall it should be built in the middle? Why should one of them contribute more than the other?

לָא צְרִיכָא – דִּקְדֵים חַד וְרַצְּיֵּיהּ לְחַבְרֵיהּ; מַהוּ דְּתֵימָא, מָצֵי אָמַר לֵיהּ: כִּי אִיתְרְצַאי לָךְ – בְּאַוֵּירָא, בְּתַשְׁמִישְׁתָּא – לָא אִיתְרְצַאי לָךְ; קָא מַשְׁמַע לַן.

The Gemara answers: No, it is necessary to state this halakha in a case where one of the partners went ahead and convinced the other that they should build a partition. Lest you say that the second can later say to the first when the latter comes to begin construction: When I was persuaded by you to build a partition, it was with regard to the airspace. I agreed to the erection of a minimal barrier that would result in a loss of open space in the courtyard. But I was not persuaded by you with regard to the use of the courtyard. I did not agree to forfeit any usable space on the ground in my share of the courtyard for the building of a wall. To counter this, the mishna teaches us that since they agreed to make a partition, they must each contribute a part of the courtyard for the building of the wall.

וְהֶיזֵּק רְאִיָּה לָאו שְׁמֵיהּ הֶיזֵּק?! (סִימָן: גִּינָּה, כּוֹתֶל, כּוֹפִין, וְחוֹלְקִין, חַלּוֹנוֹת, דְּרַב נַחְמָן).

§ After having determined that the wording of the mishna is unproblematic only if the term meḥitza means a wall, it follows that damage caused by sight is not called damage. The Gemara asks: And is damage caused by sight in fact not called damage? The Gemara provides a mnemonic for the proofs, which follow, that challenge this assumption: Garden, wall, compels, and they divide, windows, as Rav Naḥman.

תָּא שְׁמַע: ״וְכֵן בְּגִינָּה״!

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear that which the mishna teaches: And similarly with regard to a garden, in a place where it is customary to build a partition in the middle of a garden jointly owned by two people, and one of them wishes to build such a partition, the court obligates his neighbor to join in building the partition. This indicates that invading one’s privacy by looking at him while he is in his private domain is called damage.

גִּינָּה שָׁאנֵי, כִּדְרַבִּי אַבָּא – דְּאָמַר רַבִּי אַבָּא אָמַר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר רַב: אָסוּר לָאָדָם לַעֲמוֹד בִּשְׂדֵה חֲבֵירוֹ בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁהִיא עוֹמֶדֶת בְּקָמוֹתֶיהָ.

The Gemara answers: A garden is different with regard to the halakha governing invasion of privacy, in accordance with the statement of Rabbi Abba, as Rabbi Abba says that Rav Huna says that Rav says: It is prohibited for a person to stand in another’s field and look at his crop while the grain is standing, because he casts an evil eye upon it and thereby causes him damage, and the same is true for a garden. Since the issue in this case is damage resulting from the evil eye, no proof can be brought with regard to the matter of damage caused by sight.

וְהָא ״וְכֵן״ קָתָנֵי! אַגְּוִיל וְגָזִית.

The Gemara objects: But the mishna teaches: And similarly with regard to a garden, which suggests that a garden and a courtyard are governed by the same rationale. The Gemara answers: The term: And similarly, is stated not with regard to the reason for the obligation to construct a wall, but with regard to the halakha concerning non-chiseled and chiseled stones. A partition in a garden is built with the same materials used for the building of a wall in a courtyard, in accordance with regional custom.

תָּא שְׁמַע: כּוֹתֶל חָצֵר שֶׁנָּפַל – מְחַיְּיבִין אוֹתוֹ לִבְנוֹת עַד אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת! נָפַל שָׁאנֵי.

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear a proof from a mishna (5a): In the case of a dividing wall in a jointly owned courtyard that fell, if one of the owners wishes to rebuild the wall, the court obligates the other owner to build the wall with him again up to a height of four cubits. This indicates that damage caused by sight is called damage. The Gemara rejects this proof: The case of a wall that fell is different; since a wall had already stood there, the court compels the owners to rebuild it as it was.

וּדְקָאָרֵי לַהּ מַאי קָאָרֵי לַהּ? סֵיפָא אִיצְטְרִיכָא לֵיהּ – מֵאַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת וּלְמַעְלָה אֵין מְחַיְּיבִין אוֹתוֹ.

The Gemara expresses its astonishment: And he who asked the question, why did he ask it at all? The mishna is clearly referring to a wall that has fallen, which means that the joint owners have already agreed in the past to build a partition between their respective portions. The Gemara answers: He who asked the question maintains that the joint owners can be compelled to build a wall even in a case where a wall had not stood there before, to prevent any invasion of privacy. And the mishna does not address the case of a wall that fell to teach that only in such a case is there an obligation to build a wall. Rather, it was necessary to teach the latter clause, which states that even in a case where there had previously been a high wall the court does not obligate him to rebuild it higher than four cubits, because once there is a wall of four cubits there is no further invasion of privacy.

תָּא שְׁמַע: כּוֹפִין אוֹתוֹ לִבְנוֹת בֵּית שַׁעַר וְדֶלֶת לֶחָצֵר. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ, הֶיזֵּק רְאִיָּה שְׁמֵיהּ הֶיזֵּק! הַזִּיקָא דְרַבִּים שָׁאנֵי.

The Gemara suggests: Come and hear an additional proof that damage caused by sight is called damage, from what is taught in a mishna (7b): The residents of a courtyard can compel each inhabitant of that courtyard to financially participate in the building of a gatehouse and a door to the jointly owned courtyard, so that the courtyard not be open to the eyes of those standing in the public domain. Learn from it that damage caused by sight is called damage. The Gemara answers: This is not a proof to the halakha in the case of two neighbors, as the damage of being exposed to the gaze of the general public, which has unimpeded sight of what is happening in the courtyard, is different and certainly called damage.

וּדְיָחִיד לָא? תָּא שְׁמַע: אֵין חוֹלְקִין אֶת הֶחָצֵר, עַד שֶׁיְּהֵא בָּהּ אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת לָזֶה וְאַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת לָזֶה. הָא יֵשׁ בָּהּ כְּדֵי לָזֶה וּכְדֵי לָזֶה – חוֹלְקִין; מַאי, לָאו בְּכוֹתֶל? לָא, בִּמְסִיפָס בְּעָלְמָא.

The Gemara asks: And is exposure to the sight of an individual not considered damage? Come and hear a proof that it is called damage from what is taught in a mishna (11a): One divides a courtyard at the request of one of the co-owners only if its area is sufficient so that there will be in it four by four cubits for this one and four by four cubits for that one, that is, the same minimal dimensions for each of the co-owners. This means that if there is enough for this one and enough for that one, they do divide the courtyard at the request of one of the owners. What, is it not so that the courtyard must be divided with a wall that will prevent one neighbor from seeing the other? The Gemara answers: No, perhaps it is divided with a mere partition of pegs through which one can still see.

תָּא שְׁמַע: הַחַלּוֹנוֹת, בֵּין מִלְּמַעְלָה בֵּין מִלְּמַטָּה וּבֵין מִכְּנֶגְדָּן – אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת. וְתָנֵי עֲלַהּ: מִלְּמַעְלָן – כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יָצִיץ וְיִרְאֶה; מִלְּמַטָּן – כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יַעֲמוֹד וְיִרְאֶה; מִכְּנֶגְדָּן – כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יַאֲפִיל!

The Gemara further suggests: Come and hear another proof that damage caused by sight is called damage from what is taught in a mishna (22a): One who desires to build a wall opposite the windows of a neighbor’s house must distance the wall four cubits from the windows, whether above, below, or opposite. And a baraita is taught with regard to that mishna: Concerning the requirement of a distance above, the wall must be high enough so that one cannot peer into the window and see into the window; concerning the requirement of a distance below, the wall must be low so that he will not be able to stand on top of it and see into the window; and concerning the requirement of a distance opposite, one must distance the wall from the windows so that it will not darken his neighbor’s house by blocking the light that enters the house through the window. This indicates that there is a concern about the damage caused by exposure to the gaze of others.

הֶזֵּיקָא דְבַיִת שָׁאנֵי.

The Gemara rejects this argument: The damage of being exposed to the sight of others while in one’s own house is different, as people engage in activities in their homes that they do not want others to see. By contrast, a courtyard is out in the open and it is possible that the residents are indifferent to being observed.

תָּא שְׁמַע, דְּאָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר שְׁמוּאֵל: גַּג הַסָּמוּךְ לַחֲצַר חֲבֵירוֹ – עוֹשִׂין לוֹ מַעֲקֶה גָּבוֹהַּ אַרְבַּע אַמּוֹת! שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר לֵיהּ בַּעַל הֶחָצֵר לְבַעַל הַגָּג: לְדִידִי קְבִיעָה לִי תַּשְׁמִישִׁי, לְדִידָךְ לָא קְבִיעָה לָךְ תַּשְׁמִישְׁתָּךְ; וְלָא יָדַעְנָא בְּהֵי עִידָּנָא סְלִיקָא וְאָתֵית –

The Gemara challenges this distinction: Come and hear a proof, as Rav Naḥman says that Shmuel says: If one’s roof is adjacent to another’s courtyard, he must make a parapet around the roof four cubits high so that he will not be able to see into his neighbor’s courtyard. This indicates that the damage of being exposed to the eyes of others even in a courtyard is called damage. The Gemara refutes this proof: The situation is different there, as the owner of the courtyard can say to the owner of the roof: I make use of my courtyard on a regular basis. You, by contrast, do not make use of your roof on a regular basis, but only infrequently. Consequently, I do not know when you will go up to the roof,