The gemara concludes from the previous discussion that a lulav has sanctity of the shmita year, k’dushat shviit. A difficulty is raised – why should there be a k’dushat shviit in a lulav if it appears in a braita that leaves of a tree do not have k’dushat shviit if they are not collected for eating? The answer is that there is a difference between the trees who provide enjoyment after they are destroyed and the lulav whose enjoyment is at the same time as its destruction (same as produce that is eaten). There is controversy over this point about whether trees not collected for eating would have k’dushat shviit. For what needs can a k’dushat shviit fruit be used – how do Tana Kama and Rabbi Yossi disagree on this matter? Rabbi Elazar and Rabbi Yochanan disagree regarding passing on sanctification of shmita produce to other items – money, other foods, etc. Is it done only by a sale or also by redeeming it (like second tithes)? The gemara brings the reason behind each opinion and also braitot to support each opinion.

Sukkah 40

Share this shiur:

Want to dedicate learning? Get started here:

New to Talmud?

Check out our resources designed to help you navigate a page of Talmud – and study at the pace, level and style that fits you.

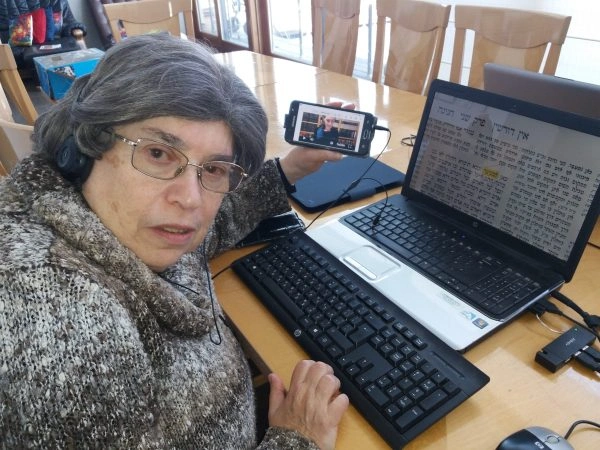

The Hadran Women’s Tapestry

Meet the diverse women learning Gemara at Hadran and hear their stories.

Sukkah 40

שֶׁבִּשְׁעַת לְקִיטָתוֹ עִישּׂוּרוֹ, דִּבְרֵי רַבָּן גַּמְלִיאֵל. רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: אֶתְרוֹג שָׁוֶה לָאִילָן לְכׇל דָּבָר.

It is like a vegetable in that at the time of its picking it is tithed; this is the statement of Rabban Gamliel. If it was picked in the third year of the Sabbatical cycle, poor man’s tithe is separated although it ripened in the second year, when the obligation is to separate second tithe and not poor man’s tithe. Rabbi Eliezer says: The halakhic status of the fruit of an etrog tree is like that of a typical fruit tree in every matter. In any case, with regard to ascribing the status of Sabbatical-Year produce to the fruits, it is apparent from the mishna that the status of an etrog of the sixth year that was picked in the seventh year is that of sixth-year produce.

הוּא דְּאָמַר כִּי הַאי תַּנָּא דְּתַנְיָא: אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי: אַבְטוּלְמוֹס הֵעִיד מִשּׁוּם חֲמִשָּׁה זְקֵנִים: אֶתְרוֹג אַחַר לְקִיטָה לַמַּעֲשֵׂר, וְרַבּוֹתֵינוּ נִמְנוּ בְּאוּשָׁא וְאָמְרוּ בֵּין לַמַּעֲשֵׂר בֵּין לַשְּׁבִיעִית.

The Gemara answers: It was the tanna of the mishna that distinguishes between the lulav and the etrog who stated his opinion in accordance with the statement of that tanna, as it is taught in a baraita that Rabbi Yosei said that Avtolemos, one of the Sages, testified in the name of five Elders: The status of an etrog is determined by the time of its picking with regard to the halakhot of tithes. And our Sages were counted in Usha, reached a decision, and said: The status of an etrog is determined by the time of its picking both with regard to the halakhot of tithes and with regard to the halakhot of the Sabbatical Year.

שְׁבִיעִית מַאן דְּכַר שְׁמֵיהּ? חַסּוֹרֵי מִיחַסְּרָא וְהָכִי קָתָנֵי: אֶתְרוֹג אַחַר לְקִיטָה לַמַּעֲשֵׂר, וְאַחַר חֲנָטָה לַשְּׁבִיעִית. וְרַבּוֹתֵינוּ נִמְנוּ בְּאוּשָׁא וְאָמְרוּ: אֶתְרוֹג בָּתַר לְקִיטָה, בֵּין לַמַּעֲשֵׂר בֵּין לַשְּׁבִיעִית.

The Gemara questions the formulation of the baraita: With regard to the Sabbatical Year, who mentioned it? As no previous mention was made of the Sabbatical Year, the discussion of the status of an etrog during the Sabbatical Year is a non sequitur. The Gemara answers: The baraita is incomplete, and this is what it is teaching: The status of an etrog is determined by the time of its picking with regard to the halakhot of tithes and determined by the time of its ripening with regard to the Sabbatical Year. And our Sages were counted in Usha and said: The status of an etrog is determined by the time of its picking both with regard to the halakhot of tithes and with regard to the halakhot of the Sabbatical Year.

טַעְמָא דְּלוּלָב בַּר שִׁשִּׁית הַנִּכְנָס לִשְׁבִיעִית הוּא, הָא דִּשְׁבִיעִית קָדוֹשׁ, אַמַּאי? עֵצִים בְּעָלְמָא הוּא, וְעֵצִים אֵין בָּהֶן מִשּׁוּם קְדוּשַּׁת שְׁבִיעִית! (דִּתְנַן:) עֲלֵי קָנִים וַעֲלֵי גְפָנִים שֶׁגִּבְּבָן לְחוּבָּה עַל פְּנֵי הַשָּׂדֶה, לִקְּטָן לַאֲכִילָה — יֵשׁ בָּהֶן מִשּׁוּם קְדוּשַּׁת שְׁבִיעִית, לִקְּטָן לְעֵצִים — אֵין בָּהֶן מִשּׁוּם קְדוּשַּׁת שְׁבִיעִית.

§ The Gemara resumes its discussion of the mishna: The reason that a lulav may be purchased from an am ha’aretz during the Sabbatical Year is specifically that it is a lulav of the sixth year that is entering the seventh. This indicates by inference that a lulav of the seventh year is sacred with the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year. The Gemara asks: Why is it sacred? It is merely wood, and wood is not subject to the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year, as it was taught in a baraita: With regard to reed leaves and vine leaves that one piled for storage upon the field, if he gathered them for eating, they are subject to the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year; if he gathered them for use as wood, e.g., for kindling, they are not subject to the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year. Apparently, wood or any other non-food product is not subject to the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year.

שָׁאנֵי הָתָם, דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״לָכֶם לְאׇכְלָה״. ״לָכֶם״ דּוּמְיָא דִּלְאָכְלָה — מִי שֶׁהֲנָאָתוֹ וּבִיעוּרוֹ שָׁוֶה. יָצְאוּ עֵצִים, שֶׁהֲנָאָתָן אַחַר בִּיעוּרָן.

The Gemara answers: It is different there, in the case of the reed and vine leaves, as the verse states: “And the Sabbatical produce of the land shall be for you for food” (Leviticus 25:6). From the juxtaposition of the term: For you, and the term: For food, it is derived: For you is similar to for food; the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year takes effect on those items whose benefit and whose consumption coincide. Wood is excluded, as its benefit is subsequent to its consumption. The primary purpose of kindling wood is not accomplished with the burning of the wood; rather, it is with the charcoal that heats the oven. Therefore, it is not subject to the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year.

וְהָאִיכָּא עֵצִים דְּמִשְׁחַן, דַּהֲנָאָתָן וּבִיעוּרָן שָׁוֶה! אָמַר רָבָא: סְתָם עֵצִים, לְהַסָּקָה הֵן עוֹמְדִין.

The Gemara objects: But isn’t there wood used to provide heat (Rabbeinu Ḥananel), whose benefit coincides with its consumption? Rava said: Undesignated wood exists for fuel, i.e., charcoal, so its benefit is subsequent to its consumption.

וְעֵצִים לְהַסָּקָה, תַּנָּאֵי הִיא, דְּתַנְיָא: אֵין מוֹסְרִין פֵּירוֹת שְׁבִיעִית לֹא לְמִשְׁרָה וְלֹא לִכְבוּסָה. רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: מוֹסְרִין.

§ The Gemara notes: The matter of whether kindling wood, whose benefit is subsequent to its consumption, is subject to the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year is a dispute between tanna’im, as it is taught in a baraita: One may neither transfer Sabbatical-Year produce, e.g., wine, for soaking flax to prepare it for spinning, as the benefit derived from the flax is subsequent to its soaking, when the soaked and spun thread is woven into a garment; nor for laundering with it, as the benefit derived is subsequent to the laundering when one wears the clean clothes. Soaking the flax or laundering the garment in wine is consumption of the wine, as it is no longer potable. Rabbi Yosei says: One may transfer Sabbatical-Year produce for those purposes.

מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ דְּתַנָּא קַמָּא — דְּאָמַר קְרָא: ״לְאׇכְלָה״, וְלֹא לְמִשְׁרָה וְלֹא לִכְבוּסָה. מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי — אָמַר קְרָא: ״לָכֶם״, ״לָכֶם״ לְכׇל צׇרְכֵיכֶם, וַאֲפִילּוּ לְמִשְׁרָה וְלִכְבוּסָה. וְתַנָּא קַמָּא, הָא כְּתִיב ״לָכֶם״! הַהוּא ״לָכֶם״ דּוּמְיָא דִּלְאׇכְלָה: מִי שֶׁהֲנָאָתוֹ וּבִיעוּרוֹ שָׁוֶה, יָצְאוּ מִשְׁרָה וּכְבוּסָה — שֶׁהֲנָאָתָן אַחַר בִּיעוּרָן.

The Gemara asks: What is the rationale for the statement of the first tanna? It is as the verse states with regard to Sabbatical-Year produce: “For food,” from which it is inferred: And not for soaking and not for laundering. What is the rationale for the statement of Rabbi Yosei permitting one to do so? It is as the verse states: “For you,” from which it is inferred: For you, for all your needs, and even for soaking and for laundering. The Gemara asks: But according to the first tanna, isn’t it written: “For you”? How does he explain that term? The Gemara answers: From that term “for you” it is derived: For you, similar to for food; the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year takes effect on those items whose benefit and whose consumption coincide, which excludes soaking and laundering, where the items’ benefit is subsequent to their consumption.

וְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי, הָא כְּתִיב ״לְאׇכְלָה״! הַהוּא מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ ״לְאׇכְלָה״ וְלֹא לִמְלוּגְמָא. כִּדְתַנְיָא: ״לְאׇכְלָה״ — וְלֹא לִמְלוּגְמָא. אַתָּה אוֹמֵר ״לְאׇכְלָה״ וְלֹא לִמְלוּגְמָא, אוֹ אֵינוֹ אֶלָּא וְלֹא לִכְבוּסָה? כְּשֶׁהוּא אוֹמֵר ״לָכֶם״, הֲרֵי לִכְבוּסָה אָמוּר. הָא מָה אֲנִי מְקַיֵּים ״לְאׇכְלָה״ — ״לְאׇכְלָה״ וְלֹא לִמְלוּגְמָא. מָה רָאִיתָ לְרַבּוֹת אֶת הַכְּבוּסָה וּלְהוֹצִיא אֶת הַמְּלוּגְמָא?

The Gemara asks: But according to Rabbi Yosei, isn’t it written: “For food,” indicating that it may not be used for any other purpose? The Gemara answers: He needs that phrase to teach: For food, and not for a remedy [melugma], as it is taught in a baraita: For food and not for a remedy. The baraita continues: Do you say: For food and not for a remedy, or perhaps it is only: For food and not for laundering? When the verse says: “For you,” for laundering is already stated as permitted since it includes all one’s bodily needs. How, then, do I uphold that which the verse states: “For food”? It is: For food, and not for a remedy. And should one ask: What did you see that led you to include the use of Sabbatical-Year produce for laundering and to exclude the use of Sabbatical-Year produce as a remedy?

מְרַבֶּה אֲנִי אֶת הַכְּבוּסָה שֶׁשָּׁוָה בְּכׇל אָדָם, וּמוֹצִיא אֶת הַמְּלוּגְמָא שֶׁאֵינָהּ שָׁוָה לְכׇל אָדָם.

Rabbi Yosei could respond: I include laundering, which applies equally to every person, as everyone needs clean clothes, and I exclude a remedy, which does not apply equally to every person; it is only for the ill.

מַאן תְּנָא לְהָא דְּתָנוּ רַבָּנַן: ״לְאׇכְלָה״ — וְלֹא לִמְלוּגְמָא, ״לְאׇכְלָה״ — וְלֹא לְזִילּוּף, ״לְאׇכְלָה״ — וְלֹא לַעֲשׂוֹת מִמֶּנָּה אַפִּיקְטְוִיזִין? כְּמַאן — כְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי. דְּאִי רַבָּנַן, הָא אִיכָּא נָמֵי מִשְׁרָה וּכְבוּסָה.

The Gemara asks: Who is the tanna who taught that which the Sages taught in a baraita with regard to Sabbatical-Year produce: For food, and not for a remedy; for food, and not for sprinkling wine in one’s house to provide a pleasant fragrance; for food, and not to make it an emetic [apiktoizin] to induce vomiting? In accordance with whose opinion is this baraita? It is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yosei, as, if it were in accordance with the opinion of the Rabbis, isn’t there also soaking and laundering that should have been excluded in the baraita, as in their opinion, use of Sabbatical-Year produce for those purposes is prohibited?

אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר: אֵין שְׁבִיעִית מִתְחַלֶּלֶת אֶלָּא דֶּרֶךְ מִקָּח. וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר: בֵּין דֶּרֶךְ מִקָּח בֵּין דֶּרֶךְ חִילּוּל.

§ Rabbi Elazar said: Sabbatical-Year produce is deconsecrated only by means of purchase; however, it cannot be deconsecrated through redemption. Merely declaring that the sanctity of that produce is transferred to money or other produce is ineffective. Rabbi Yoḥanan said: It is deconsecrated both by means of purchase and by means of redemption.

מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר? דִּכְתִיב: ״בִּשְׁנַת הַיּוֹבֵל הַזֹּאת וְגוֹ׳״, וּסְמִיךְ לֵיהּ: ״וְכִי תִמְכְּרוּ מִמְכָּר״, דֶּרֶךְ מִקָּח וְלֹא דֶּרֶךְ חִילּוּל. וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן מַאי טַעְמֵיהּ? דִּכְתִיב: ״כִּי יוֹבֵל הִיא קֹדֶשׁ״. מָה קֹדֶשׁ — בֵּין דֶּרֶךְ מִקָּח בֵּין דֶּרֶךְ חִילּוּל, אַף שְׁבִיעִית — בֵּין דֶּרֶךְ מִקָּח בֵּין דֶּרֶךְ חִילּוּל.

What is the rationale for the opinion of Rabbi Elazar? It is as it is written: “In this year of Jubilee you shall return every man unto his possession” (Leviticus 25:13), and juxtaposed to it it is written: “And if you sell an item to your neighbor” (Leviticus 25:14); this indicates that in the Jubilee Year, during which the halakhot of the Sabbatical Year are in effect, one deconsecrates the produce by means of purchase and not by means of redemption. The Gemara asks: And Rabbi Yoḥanan, what is the rationale for his opinion? It is as it is written: “For it is a Jubilee; it shall be consecrated unto you” (Leviticus 25:12); this indicates that just as one redeems consecrated items both by means of purchase and by means of redemption, so too, Sabbatical-Year produce can be redeemed both by means of purchase and by means of redemption.

וְרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, הַאי ״כִּי תִמְכְּרוּ מִמְכָּר״ מַאי עָבֵיד לֵיהּ? מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְכִדְרַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא. דְּתַנְיָא, אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בַּר חֲנִינָא: בּוֹא וּרְאֵה כַּמָּה קָשֶׁה אֲבָקָהּ שֶׁל שְׁבִיעִית וְכוּ׳. אָדָם נוֹשֵׂא וְנוֹתֵן בְּפֵירוֹת שְׁבִיעִית, לְסוֹף מוֹכֵר אֶת מִטַּלְטְלָיו וְאֶת כֵּלָיו, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״בִּשְׁנַת הַיּוֹבֵל הַזֹּאת תָּשֻׁבוּ אִישׁ אֶל אֲחוּזָּתוֹ״, וּסְמִיךְ לֵיהּ: ״וְכִי תִמְכְּרוּ מִמְכָּר לַעֲמִיתֶךָ וְגוֹ׳״.

The Gemara asks: And Rabbi Yoḥanan, what does he do with this juxtaposition of the Jubilee Year to the verse: “If you sell an item”? The Gemara answers: He needs it to derive a halakha in accordance with that statement of Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina, as it is taught in a baraita that Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina says: Come and see how severe even the hint of violation of the prohibition of the Sabbatical Year is; as the prohibition against commerce with Sabbatical-Year produce is not one of the primary prohibitions of the Sabbatical Year, and its punishment is harsh. A person who engages in commerce with Sabbatical-Year produce is ultimately punished with the loss of his wealth to the point that he is forced to sell his movable property and his vessels, as it is stated: “In this year of Jubilee you shall return every man unto his possession” (Leviticus 25:13), and juxtaposed to it, it is written: “And if you sell an item to your neighbor” (Leviticus 25:14).

וְרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר, הַאי קְרָא דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן מַאי עָבֵיד לֵיהּ? מִיבְּעֵי לֵיהּ לְכִדְתַנְיָא: ״כִּי יוֹבֵל הִיא קֹדֶשׁ״. מָה קֹדֶשׁ תּוֹפֵס אֶת דָּמָיו — אַף שְׁבִיעִית תּוֹפֶסֶת אֶת דָּמֶיהָ.

The Gemara asks: And Rabbi Elazar, what does he do with this verse from which Rabbi Yoḥanan derived his opinion? The Gemara answers: He needs it to derive in accordance with that which is taught in a baraita: “For it is a Jubilee; it shall be consecrated unto you” (Leviticus 25:12); just as the sanctity of consecrated items takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which they are redeemed, so too, the sanctity of Sabbatical-Year produce takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which it is redeemed.

תַּנְיָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר, וְתַנְיָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן. תַּנְיָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר: שְׁבִיעִית תּוֹפֶסֶת אֶת דָּמֶיהָ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״כִּי יוֹבֵל הִיא קֹדֶשׁ תִּהְיֶה לָכֶם״, מָה קֹדֶשׁ תּוֹפֵס אֶת דָּמָיו — וְאָסוּר, אַף שְׁבִיעִית תּוֹפֶסֶת אֶת דָּמֶיהָ — וַאֲסוּרָה.

It is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Elazar, and it is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan. The Gemara elaborates that it is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Elazar: Sabbatical-Year sanctity takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which the produce is redeemed, as it is stated: “For it is a Jubilee; it shall be consecrated unto you”; just as the sanctity of consecrated items takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which they are redeemed and it is prohibited to use the money for non-sacred purposes, so too, the sanctity of Sabbatical-Year produce takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which it is redeemed, and it is prohibited to use this money for purposes for which Sabbatical-Year produce may not be used.

אִי, מָה קֹדֶשׁ תּוֹפֵס דָּמָיו — וְיוֹצֵא לְחוּלִּין, אַף שְׁבִיעִית תּוֹפֶסֶת אֶת דָּמֶיהָ — וְיוֹצֵאת לְחוּלִּין? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״תִּהְיֶה״, בַּהֲוָיָיתָהּ תְּהֵא.

Or perhaps extend the analogy and derive that just as the sanctity of consecrated items takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which they are redeemed, and the consecrated item assumes non-sacred status, so too, the sanctity of Sabbatical-Year produce takes effect on money or objects in exchange for which it is redeemed, and the Sabbatical-Year produce assumes non-sacred status. Therefore, the verse states: “It shall be consecrated unto you,” meaning: It shall be as it is. Although the sanctity of Sabbatical-Year produce takes effect on the money, the produce remains consecrated as well.

הָא כֵּיצַד? לָקַח בְּפֵירוֹת שְׁבִיעִית בָּשָׂר — אֵלּוּ וָאֵלּוּ מִתְבַּעֲרִין בַּשְּׁבִיעִית. לָקַח בַּבָּשָׂר דָּגִים — יָצָא בָּשָׂר וְנִכְנְסוּ דָּגִים. לָקַח בַּדָּגִים יַיִן — יָצְאוּ דָּגִים וְנִכְנַס יַיִן. לָקַח בַּיַּיִן שֶׁמֶן — יָצָא יַיִן וְנִכְנַס שֶׁמֶן.

The Gemara explains: How so? If one purchased meat with Sabbatical-Year produce, both this, the produce, and that, the meat, must be removed during the Sabbatical Year. The meat may be eaten only as long as the produce in exchange for which it was purchased may be eaten, i.e., as long as produce of that kind remains in the field. However, if he purchased fish in exchange for the meat, the meat emerges from its consecrated status, and the fish assumes consecrated status. If he then purchased wine in exchange for the fish, the fish emerges from its consecrated status, and the wine assumes consecrated status. If he purchased oil in exchange for the wine, the wine emerges from its consecrated status, and the oil assumes consecrated status.

הָא כֵּיצַד: אַחֲרוֹן אַחֲרוֹן נִכְנָס בַּשְּׁבִיעִית, וּפְרִי עַצְמוֹ אָסוּר. מִדְּקָתָנֵי ״לָקַח״ ״לָקַח״, אַלְמָא דֶּרֶךְ מִקָּח — אִין, דֶּרֶךְ חִילּוּל — לָא.

How so? The last item purchased assumes the consecrated status of produce of the Sabbatical Year, and the produce itself remains consecrated and forbidden and never loses its consecrated status. The Gemara notes: From the fact that the baraita teaches each case using the term: Purchased, purchased, apparently it means that by means of transaction, yes, the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year takes effect; however, by means of redemption, no, the sanctity of the Sabbatical Year does not take effect.

תַּנְיָא כְּווֹתֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: אֶחָד שְׁבִיעִית וְאֶחָד מַעֲשֵׂר שֵׁנִי מִתְחַלְּלִין עַל בְּהֵמָה חַיָּה וָעוֹף, בֵּין חַיִּין בֵּין שְׁחוּטִין, דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי מֵאִיר. וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: עַל שְׁחוּטִין — מִתְחַלְּלִין, עַל חַיִּין — אֵין מִתְחַלְּלִין, גְּזֵירָה שֶׁמָּא יְגַדֵּל מֵהֶן עֲדָרִים.

The Gemara continues: It is taught in a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan. Both Sabbatical-Year produce and second-tithe produce are deconsecrated upon domesticated animals, undomesticated animals, and fowl, whether they are alive or whether they are slaughtered; this is the statement of Rabbi Meir. And the Rabbis say: Upon slaughtered animals, they are deconsecrated; upon animals that are alive, they are not deconsecrated. The reason is that a rabbinic decree was issued lest one raise flocks from them. If one breeds a herd from that consecrated animal, the entire herd would be sacred and the potential for misuse of second-tithe property would be great.

אָמַר רָבָא: מַחְלוֹקֶת

Rava said: This dispute between Rabbi Meir and the Rabbis